Lanark, UK, August 6th - 13th, 1910

Lots of flying and nice weather, but yet another financial failure...

Lanark is a small town in the central belt of

Scotland, located around 45 kilometres southeast of

Glasgow, close to the river Clyde. It has been a market

town since medieval times and was originally the county

town of Lanarkshire, but lost that status to Glasgow in

1890. In 1910 it had around 7,000 inhabitants. There was

a couple of textile factories and tanneries, but

otherwise the town's economy relied on cattle trading

and fruit-growing. One of the attractions of the town is

the beautiful Clyde Falls south of the town.

The Fédération Aéronautique Internationale allotted two

international aviation meetings to Britain in 1910. The

first meeting was given to the Lancashire Aero Club and

Bournemouth. In February, the Scottish Aeronautical

Society made a bid to organize the second, at the Lanark

racecourse. The decision was taken in April, and

preparations started. An organizing committee was formed,

headed by the Duke of Argyll. It was decided to use the

racecourse for hangars and public enclosures, while a

flying course was laid out on the fields east of the

existing installations. The course was reached after a

starting straight of around one kilometre, which would

also be used for take-off contest and the "dispatch

carrying competition" in which the competitors

dropped "messages" on a target.

Lanark only had two hotels, and both were booked up far

in advance of the meeting. This wasn't a huge

disadvantage, since there were good train services from

Glasgow and from Edinburgh, both some 45 kilometres away.

The Caledonian Railway Company had built a temporary

station at the airfield, which they claimed could handle

30,000 passengers per day.

A company was registered, the "Scottish

International Aviation Meeting, 1910", and a

guarantee fund of £ 12,000 was collected. The total prize

money was set at £ 8,000. Messrs. Norman and McKnight of

Glasgow were contracted as official aeronautical and

repairing engineers, providing an up-to-date workshop

with machinery, a staff of trained builders and

mechanics, and a large selection of spare parts.

The meeting, which was the most important in Britain to

that date, attracted 22 entrants. With exception for

Claude Grahame-White, who was contracted to fly at the

coinciding Blackpool Flying Carnival, almost all

accomplished British flyers were present. The field also

included several experienced foreign flyers, for example

"Géo" Chávez, Marcel Hanriot, Bartolomeo

Cattaneo, Edmond Audemars, Gijs Küller and

"Edmond" (Edmond Morelle). The day before the

start of the meeting the machines of Chávez and Küller

were unfortunately destroyed by fire on the North-Western

Railway, close to Lancaster, on the way to the meeting.

Three more machines, the Hanriot of René Vidart, the

Tellier of Edmond Audemars and the Short of George

Colmore had gone missing on the railway and were delayed,

so the British railway operators had no reason to

celebrate. Maurice Tétard, who had entered, decided to

stay in Blackpool, where he probably had a guaranteed

purse.

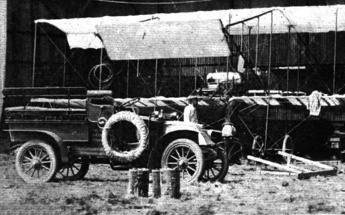

Work at the airfield had progressed smoothly and

efficiently. Everything was ready in time, and the

quality of the hangars, which were solidly built and even

had corrugated metal roofs, was praised. Safety was

stressed in the regulations, which strongly decreed that

a competitor should only pass on the outside of the

competitor to be passed. The overtaking pilot was held

responsible for clearing the overtaken competitor and had

to keep at such a distance that the overtaken competitor

had undisturbed air in which to travel. In the interest

of safety, the announced precision landing contest was

cancelled. Official flights could take place between noon

and sunset.

Saturday 6 August

The first day of the meeting was windy and misty. Several

of the competitors were still busy assembling and

preparing their machines. Bertram Dickson was ready,

however, and made the first flight. He made a two-lap

flight of seven minutes, obviously troubled by the wind.

The reason for giving up the flight and landing was a

broken inlet valve, but he still returned to make a

perfect landing. The wind, which was measured to around 8

m/s during Dickson's flight, calmed down somewhat

during the afternoon and at half past three he was

followed by Cattaneo, and then by John Armstrong Drexel

and Gustave Blondeau. Drexel's total flying time was

1 hour 48 minutes, putting him far in the lead in the

endurance contests, while Cattaneo in his Gnôme-powered

Blériot took the lead in the speed contests. Late in the

evening Graham Gilmour took out his JAP-powered Blériot

and made a flight outside the airfield. After eleven

minutes it started raining and he was forced down.

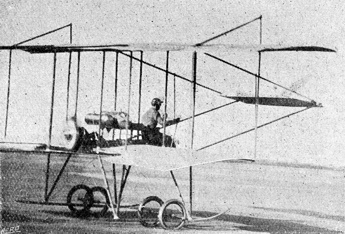

Sunday 7 August

No official flights were scheduled during the Sunday, but

several pilots made test flights. One of them was

"Edmond" (Edmond Morelle), who tried out the

Farman copy built by the British and Colonial Aeroplane

Company of Bristol. His machine had been assembled by

French Farman mechanics, who weren't aware of the

differences between the original and the copy. As a

result, it was incorrectly rigged and flew with the

ailerons on one side permanently pulled down.

Monday 8 August

This was perfect day for flying. Already before the start

of official flights, "Edmond", whose machine

had now been re-rigged, and Florentin Champel made test

flights. The first two hours of official flying were

spent on the take-off contest. James Radley had borrowed

the Gnôme-engined Blériot of Launcelot Gibbs, who

couldn't participate for medical reasons. William

McArdle, Alec Ogilvie, and George Cockburn all made

successful efforts, while Audemars, who had fitted a

heavy in-line four-cylinder engine to his Demoiselle,

couldn't even lift off. It seemed like to big engine

didn't deliver power enough to lift itself off the

ground. Gilmour scored the day's best result, with

Radley second, while McArdle's best effort was

disqualified, since he had turned back on the ground and

crossed the start line a second time. He claimed that it

was not a proper effort, but the officials didn't

agree.

While the take-off contest went on, Dickson made an

effort for the cross-country contest. His time over the

36 kilometres was 36 minutes. After his landing, McArdle

also took off for the cross-country prize. When more than

an hour had passed, people started to worry that he had

had an accident. After a long time a telegram arrived,

explaining that he had flown at high altitude, lost sight

of the ground in the mist and failed to spot the turning

point. He had continued eastward almost to Edinburgh,

some 40 kilometres away for, the airfield, before turning

back to land near Corstorphine. He landed in a field,

without doing any damage, after spending 1 hour 25

minutes in the air. The machine had to dismantled and

sent back by road during the evening. It was also

announced that McArdle had lost his wallet, containing

the rather significant sum of £ 300, during the day.

After two o'clock, the endurance flying started.

Blondeau took off, but after a couple of laps he lost one

of his ailerons. The screws that held it had pulled out

of the wood. He managed to land safely by controlling the

plane with the rudder, but after touching down a hummock

caught the horizontal wire between the landing skids. The

skids were pulled together, which made the entire landing

gear collapse and put the plane on its nose, causing

considerable damage.

Then Dickson made an effort for the passenger prize, with

a reporter from "The Aero" on board. The

minimum weight of pilot and passenger was 25 stone (159

kg), but Dickson wanted to carry more than 180 kg, so he

added extra weight by wrapping lead sheet around the

landing gear legs. The added weight was probably too much

for the circumstances, and to make things even worse his

crew had miscalculated the weight and added 6 stone too

much. It was reported that the total load was 235 kg. The

plane lost lift at the third pylon when it was exposed to

the downdraught from the hills. Dickson managed to land

safely, but while still rolling the machine ran into a

ditch that hadn't been properly filled. The landing

gear on the left side was ripped off and both the upper

and the lower wings were destroyed. Dickson reportedly

"said rude things" about the man who had filled

the ditch with straw, rather than earth. Drexel also made

an effort for the passenger prize, but his engine

didn't pull well, and he gave up already on the first

straight.

There was an interesting and potentially lethal incident

in the hangar area, when Grace's engine was started.

One of the mechanics had left a knife on the ground,

which was sucked up by the propeller and thrown far away,

fortunately without hitting somebody. The knife knocked a

piece as large as the palm of hand out of the propeller

blade.

Chávez also borrowed Gibbs' Blériot to make an effort

at the altitude prize. Clouds were building up and at

1,500 metres he was lost from sight. He soon found it too

cold and wet in his light overcoat and returned to land.

He had carried two barographs, but they didn't agree.

One showed 1,500 metres and the other 1,800 metres, and

in the end his official result was given as 1,600 metres.

This was the last official flight, but again Gilmour made

the last flight, without official timing.

In total, seven pilots had entered the endurance contest.

Cattaneo was far ahead, having scored a total of more

than three hours in the air during the day, with Drexel

second and Champel third. Radley had taken over the lead

in the speed contests.

Tuesday 9 August

The weather was bright, but there was a nasty wind of

some 9 m/s from the north in the early afternoon. Chávez

announced that he would not take further part in the

flying because of difficulties finding a replacement

airplane, and that he would return to Paris. Küller was

busy building a machine from his spares, which had been

on a different train and hadn't been burned, and

parts that were sent from France. He had a complete spare

fuselage and a set of spare wings, but he didn't have

a spare landing gear. This unique piece of equipment was

particularly problematic and several parts of it had to

be built at the airfield. He also had to send for a

replacement engine, which couldn't be tested before

fitting.

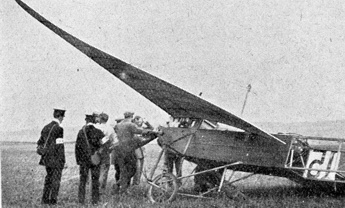

Vidart was first in the air, around noon. The wind was

still manageable, and his handling of the Hanriot

monoplane, in his first appearance at an official

aviation meeting, impressed the crowds. Vidart's

flight was followed by the first efforts for the

"Dispatch Carrying Competition". The object of

this contest was to drop a "dispatch", in the

form of a ripe orange, as close as possible to a target

in the form of a red flag in the centre of a 12-foot

diameter sheet placed on the ground. Grace and Ogilvie

made efforts, with the former taking the lead by missing

the target by 7.26 metres, beating Ogilvie's 18.90.

Ogilvie had fitted his machine with a launching tube,

made from a biscuit tin, but one of his efforts still

failed when the orange hit a rigging wire and burst.

The wind then increased, and it went quiet for a long

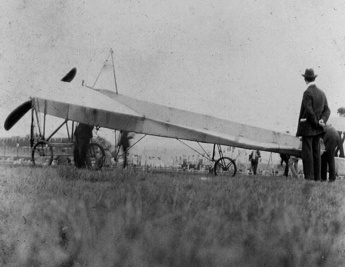

while, until Cody brought out his machine. His big

machine was intended for a 100 hp engine that hadn't

been delivered, and was underpowered with an engine of

only 65 hp. It ran the length of the field and back,

barely getting off the ground.

At around six o'clock the wind calmed down. Drexel

was first to take advantage of the improved conditions,

going for the altitude prize. He kept climbing for a long

time and eventually reached 1,039 metres. He

"afforded a remarkable lunar spectacle" by

flying across the moon like a "small insect-like

shape, which was easily enclosed between the horns of the

crescent", according to the reporter from "The

Scotsman". He descended in a long glide, only

starting his engine once in a while. While Drexel was

still in the air Cattaneo and Grace also took off for the

altitude prize, but they only reached 987 and 756 metres

respectively. Afterwards, the airfield was rather busy,

with Vidart, Grace, Ogilvie and Cattaneo all competing

for the speed prize, while Edmond tried for the slow

flying prize. There was a bit of a traffic jam and

Cattaneo had to take evasive action above the crowds when

he came across Edmond.

Meanwhile, Radley made an effort for the cross-country

prize. He made the flight in 26 minutes, but got lost on

the way back. He wore goggles, which he wasn't used

to, because he had got oil in his eyes on a previous

flight, and was blinded by the setting sun in the haze.

This made him mistake the Lanark Loch, a little lake

northwest of the airfield, for a pond outside the

airfield that he had used as a landmark. After realizing

his mistake, he spotted the roofs of the hangars and came

down to land from the wrong direction, blowing a tyre

when touching down.

Later on, Vidart, Champel and Gilmour made test flights.

Just before closing time Edmond and Grace again tried for

the slowest lap prize. Edmond did best, stretching his

time to 3:31.6, corresponding to an average speed of

around 47.5 km/h.

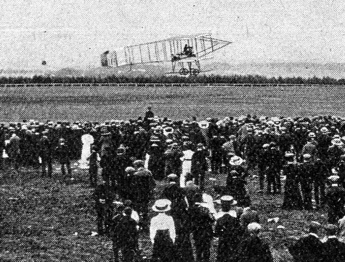

Wednesday 10 August

The weather was perfect, and since it was an "early

closing day" in many neighbouring towns a lot of

people had the chance to go to the airfield. It was

estimated that there were more than 50,000 visitors.

Several pilots made tests during the morning. The Tellier

monoplane had finally arrived, and Audemars was eager to

test it, having retired and dismantled his re-engined

Demoiselle. His first one-lap flight was successful, but

after a second flight the plane swerved on the ground and

a wing touched the ground. The landing gear and a wheel

were damaged, which necessitated a few hours of repair

work. Edmond made a heavy landing during a passenger

flight and damaged his landing gear.

The day's first contest was the starting competition.

Radley made the best start, getting off in 32.6 metres,

while McArdle was second with 33,2 metres. Drexel tried

with a passenger on board and travelled 74 metres before

rising, while Grace, also with a passenger, needed 112

metres.

Early in the afternoon Cattaneo took off for the

endurance prize. He flew lap after lap and finally landed

after 3 h 11:41.6, having flown 227 kilometres. This was

announced as a British record, beating Louis

Paulhan's London-to-Lichfield flight for the

"Daily Mail" London-Manchester Prize. Later on,

Drexel and Cattaneo entered the altitude contest, but

both broke off their efforts after encountering strong

winds and turbulence that were set up by an approaching

thunder cloud. Several pilots made passenger flights,

among them Grace and Drexel. Drexel also made three long

flights, trying to close the gap to Cattaneo in the total

distance contest.

Cattaneo, Radley and Grace flew the five laps required

for the speed contest. Radley, who made two efforts,

scored best with a time of 9:32.4, beating Cattaneo by 21

seconds and Grace on his slower biplane by almost five

minutes. Radley also scored the day's fastest lap.

Around a quarter to six McArdle and Hanriot went for the

altitude prize. McArdle reached 698 metres, the best

result of the day. Champel's engine didn't run

well, and he failed to clear a rise in the ground during

a test flight. He touched down heavily, fortunately

without breaking anything, and managed to fly back to the

hangars. He was less lucky during a second flight. He

again made a slow take-off and flew a lap before running

wide at the turn and crashing in a fir plantation south

of the course. The engine didn't give enough power to

clear the trees, but he had the presence of mind to raise

the nose and slow the plane down to sink in an almost

vertical descent into the trees, where it came to rest

several feet off the ground. He escaped injury and the

plane was relatively lightly damaged, but some thirty

trees had to be felled in order to get it out.

Vidart and Grace also suffered minor mishaps.

Vidart's engine suddenly stopped on the course,

resulting in a broken landing gear, while Grace made

heavy landing, which resulted in a dented propeller and a

broken strut. Küller's Antoinette was finally close

to completion, but he had a narrow escape during the

evening, when a lamp ignited a fuel container. A brave

mechanic suffered a burned hand, but managed to throw the

container away outside the hangar.

Cattaneo's total distance stood at 624 kilometres at

the end of the day, leading Drexel by almost 130

kilometres.

Thursday 11 August

The weather looked promising in the morning - bright and

sunny with a little heat haze, but as noon approached the

wind increased, reaching 11 m/s in the gusts. During the

morning Edmond's crew made a test to measure the

thrust of his machine. The tail of the machine was tied

to a parked car outside the hangar, with the nose

pointing towards the hangar opening. When the engine was

opened up all kinds of stuff was sucked out of the hangar

and blown far away.

The only one who cared for flying was Küller, whose crew

had finally managed to build all the missing parts and

assemble his Antoinette. He took off around half past

twelve, after a short run against the wind. When he

passed the first pylon he got the gusty wind from the

side. The wings of the Antoinette had pronounced V-form,

which made it sensible to gusts from the sides, and he

was soon in trouble. The machine rocked violently from

side to side, the engine stopped and suddenly a wing tip

hit the ground, then the other. The landing gear skid dug

into the soft ground and the machine pitched onto its

nose and remained standing with the tail high in the air.

Küller was not injured, and he climbed out and dropped to

the ground while assistance arrived. The machine was

righted, and an inspection showed surprisingly small

damages. The propeller was shattered, the skid was

broken, and a tyre had blown, but thanks to the

Antoinette's wing tip leading edge skids the only

damage to the wings was a small tear in the fabric. The

loss of power had been caused by an ignition cable that

had come loose. The machine was towed back to the

hangars, where repairs immediately started.

At half past two Drexel came out and made an effort for

the speed contest. No great results could be expected

because of the wind, but he finished his five laps,

despite having to fight to remain in control. He made a

second effort an hour and a half later, but did not

manage to improve his result. Küller's repairs were

finished at half past four and he immediately rolled out

for a new start. He hit some bumps on the uneven ground

and the skid hit the ground when the landing gear

suspension compressed. It threw up a piece of turf that

was hit by the propeller, which was damaged. The machine

was returned to the hangars, where another replacement

propeller waited. Küller had ordered four, so there were

still two left.

Around six o'clock the wind calmed down and most

pilots made flights. Grace and Dickson went for the

cross-country prize and disappeared to the northeast,

followed by the faster Blériots of McArdle and Radley.

Cattaneo turned laps for the endurance contest, while

Ogilvie and Cockburn took off for the slow flight

contest, while Grace and Edmond went for the speed

contest. McArdle returned, pleased with finding the

turning point this time, followed by Radley, Grace and

Dickson, who had also managed to complete the course. The

efforts of McArdle and Radley were disallowed, however,

because they had landed short of the finish line, which

was crowded by other planes when they arrived. They were

not pleased with the decision and filed protests, to no

avail.

Shortly before seven o'clock Drexel and McArdle

announced that they would try for the altitude contest.

After being equipped with the necessary instruments they

took off and quickly climbed into the more and more

cloudy sky. Drexel's climbing turns took him further

and further to the north, and it became obvious that he

had lost his bearings. After almost half an hour he

disappeared out of sight into a cloud. It was not known

how much fuel he carried, and people at the airfield

started to worry when he didn't return within an

hour. McArdle returned from his effort, having reached

832 metres. Hanriot also made an altitude flight, but

gave up after reaching 411 metres. Küller made another

test at seven o'clock, but the engine failed after

three laps, and he landed out on the course. The last

flights of the day were a couple of passenger trips by

Edmond and Grace. Radley had scored best in the speed

contest, while Cockburn had taken the lead in the slow

flight contest. Work was going on in the hangars, where

Cody's crew had now fitted a second Green engine in

his machine. A Howard Wright machine with ENV engine had

arrived, having been on the way for eight or nine days on

the erratic British railways. It was reportedly intended

for Champel. Colmore's machine had also finally

arrived.

For a long time there was no news of Drexel. It was by

now obvious that he had come down somewhere, and cars

were sent out to search for him. At half past nine a

telegram finally arrived: "Have landed near

farmhouse at Wester Mossat, near Cobbinshaw Station. Am

now at Cobbinshaw Station. Please send mechanics to

station". After losing his way he had finally found

a field where he could land safely, some 16 kilometres

northeast of the airfield. He had borrowed a bicycle by

the surprised farmers, whose farm was actually named

Wester Mosshat, and ridden to the railway station, where

he could telegraph for help and was served tea by the

stationmaster. When he returned to the airfield, at half

past one in the night, he stated that he had landed after

some 50 minutes and still had quite a lot of fuel, but

that he was lost, his hands were completely numb from the

cold after passing through the big wet cloud without

gloves, and to make things worse he was starting to run

out of castor oil. He had decided to land as soon as he

found a good place, since he didn't want to risk the

engine stopping while trying to find his way back to the

airfield.

Friday 12 August

The sealed barograph that Drexel had carried was opened

and investigated by officials during the early morning,

before being sent to the Kew Observatory for checking. It

showed 2,057 metres (6,750 feet), a new world record. The

old record was held by Walter Brookins, who had reached

1,904 metres in a Wright at Atlantic City on July 10th.

The climb to the maximum altitude had only taken 34

minutes.

It had rained during the night, but the morning was

bright and windy. The wind speed reached 11 m/s around

noon, so nobody went for any longer flights. The first

event, the starting contest, began at one o'clock.

Because of the direction of the wind, it was decided to

make the take-offs towards the hangar area. This was

closer to the watching crowds, but it still didn't

arouse any great enthusiasm. It led to an exciting

incident, though, when McArdle's Blériot was pitched

upwards by a gust. He had to quickly decide whether to

try to climb above the hangars or land immediately. He

chose the latter option, but overcontrolled and made a

violent touchdown. The tail rose high in the air and for

a moment it looked like the machine would turn over on

its back, but it remained standing vertically on its

nose. The impact broke the landing gear and the

propeller. Radley, Dickson, Grace, Ogilvie and Edmond

also made efforts, some of them with passengers on board.

Radley scored the best result without passenger, 17.4

metres, while Ogilvie got off the ground in 45 metres

with a passenger.

The wind then increased, reaching 13-14 m/s, and the

airfield went quiet until four o'clock, when Küller

rolled out his Antoinette and pointed it into the wind.

He needed a long roll before leaving the ground, and it

looked like the engine didn't pull well. He turned

back onto the course and flew a lap, despite the wind,

but when he turned to start the second lap he suddenly

turned right and left the course. The machine lost speed

and crashed into the same fir plantation where Champel

crashed two days earlier. The young trees cushioned the

fall and reduced the damages, but the propeller, the

landing gear and the lower wing rigging were damaged.

Workmen immediately started felling trees in order to get

it out, but it took an hour and a half before a road had

been cleared and the disassembled machine could be

brought back. Küller, who was again unhurt, explained

that the main reason for the bad performance was that the

propeller, which was a replacement for the ones burned on

the train, didn't deliver enough thrust.

The wind continued to blow, and nothing happened until

half past five, when some of the machines were paraded in

front of the grandstands. Towards the evening the winds

calmed somewhat and at half past six Grace and Dickson

rolled out their planes. Grace was first to take off and

flew four laps. Dickson continued to fly after

Grace's landing and was soon followed by Drexel.

Drexel's flight of a little more than eight minutes

was the day's longest and ended a disappointing day

for the crowds.

Saturday 13 August

The morning was again bright, but windy. The wind speed

at noon was between 7 and 9 m/s - not comfortable for

flying, but not forbidding. The first one to fly was

Cody, who had removed one of the engines again, because

it had turned out to be impossible to synchronize the two

engines. It was not a glorious flight - he took off after

a roll of around 100 metres, flew in a straight line to

the end of the course, landed, turned the plane around

and flew back only a couple of metres above the ground.

He repeated the performance twice, each time with a

passenger on board. Several pilots had signalled the

intention to fly for different contest around the time

when Cody flew, but they called off their efforts when

the wind increased again, and the next flight wasn't

made until half past one. It was Grace, who made a

13-minute flight with a passenger on board. He was

followed by Hanriot, who made two short flights,

obviously troubled by the wind.

The next flights didn't take place until a quarter

past four, when the wind had come down to 6 m/s. Several

machines had entered for a novelty: The first

straight-line speed contest in the world. Seven

competitors had entered, and they were each allowed two

efforts. Radley was first, followed by Grace, Blondeau,

Dickson, McArdle, Cattaneo and Colmore, who now made his

first flight in the plane that finally had arrived and

been assembled. They made their second efforts in the

same order, but this time Colmore left the course and

crashed outside the field. He was not injured, but the

propeller and a wing were broken. The event was won by

Radley, who with the help of the tailwind covered the

one-mile course in 47.4 seconds, corresponding to a speed

of 122.2 km/h. This was around 17 km/h faster than the

world speed record, which was set by Léon Morane at Reims

a month earlier, but since Morane's speed was clocked

over a 10-kilometre closed course the results were of

course not comparable. There was also a one-kilometre

straight-line contest, which was timed during the same

flights but over only the last part of the course. The

ground was higher at the middle of the course, so the

mile course involved climbing while the planes could

descend slightly during the second half. Therefore, the

speeds over the kilometre were slightly better. Radley

won this contest too, with a speed of 125.0 km/h.

When the speed contest was finished McArdle, Grace and

Cattaneo started for the cross-country contest, in

perfect conditions. They all finished their flights

without problems, McArdle scoring the best time of the

week with 23:04.2. Then followed a very active period,

when there were sometimes six or seven machines in the

air at the same time - Drexel, Cattaneo, Radley, Ogilvie,

Dickson, Hanriot, Champel, Edmond and Cody, all competing

for different contests or carrying passengers. Grace made

the only successful flight for the weight-carrying

contest and managed to fly the required lap with a load

of 160.5 kilograms.

During the last minutes of the meeting there were a

couple of incidents. Radley's engine stopped at an

altitude of 180 metres and his machine was damaged during

the heavy forced landing. Grace had a more alarming

accident around eight o'clock, during the last flight

of the meeting. He was carrying a passenger, professor J.

Harvard Biles of Glasgow, when the propeller suddenly

disintegrated, throwing bits and pieces in all

directions. Several of them went through the rear part of

the wings, ripped the fabric, and made the ailerons

useless. The plane dropped, out of control. It made a

very heavy landing, and a tyre blew with a sound like a

pistol shot. The landing gear collapsed and the machine

crashed down on the lower wings. The crowd broke through

the fences and ran towards the accident site, and

ambulances arrived quickly, but fortunately there were no

injuries. After this there were no more flights.

Conclusion

From a sporting point of view, Drexel's altitude

record was the high point, but it was generally agreed

that this had been the most successful aviation meeting

in Britain. There had been no serious accidents and there

had been around three times as much flying as in

Bournemouth. Cattaneo had spent a total of 8 h 35:53.6 in

the air during the meeting, beating Drexel by around an

hour and a half. Grace had taken the biggest share of the

prize money, not because of any spectacular performances,

but he had performed solidly in all contests, in a

machine that he himself considered antiquated. Because of

that, he had won all the additional prizes that were

reserved for biplanes.

The officials, the practical arrangements of the meeting

and the behaviour of the crowds were also compared

favourably with the previous meetings. Ticket sales at

the gates totalled 144,344, with 31,724 on the best day,

which was the Wednesday. To this should be added around

10,000 "season ticket" holders each day.

350,000 words had been sent by telegraph from the

airfield by reporters from the press, and around 100,000

postcards had been handled at the airfield.

The Lanark Town Council decided that the Aviation

Committee had to compensate the 270 trees that had to be

cut down after Champel's and Küller's accidents

with the sum of £ 33 15 s, but this was only a small part

of the losses. The finances were, as at so many other

meetings, very disappointing. The meeting made a loss of

£ 8,750, which had to be paid by the guarantors, who had

in total committed £ 12,000. The reasons for the

disappointing finances of aviation meetings were

discussed in the aviation press. The conclusion was that

since they gathered so many spectators and so much

attention, the reason had to be overspending from the

organizers. Three factors were particularly identified:

Expensive construction of temporary grandstands and

hangars, expensive deals with landowners around the

airfields, and expensive deals with the flyers. It was

argued that participants shouldn't both be guaranteed

appearance money and offered big cash prizes for

different contests.