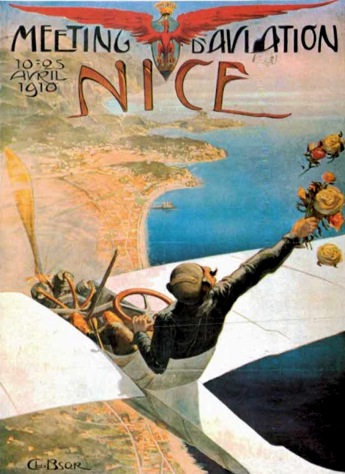

Nice, France, April 15th - 24th, 1910

Lots of flying at the successful first major French meeting of 1910

Nice is the capital of the department Alpes-Maritimes,

at the eastern end of the French Riviera. It has for a

long time been a resort for the rich and famous, due to

its mild winter climate and its casinos and beautiful

promenades. In 1910 the town had 130,000 inhabitants and

apart from tourism lived from agricultural produce, such

as oil and fruit. It was also a military town, with

several forts and batteries in the surroundings.

Nice received one of the sanctions for a 1910 meeting

that were granted by the Aéro-Club de France. It was

organized by the town of Nice, with support from the

Aéro-Club de France and the Aéro-Club de Nice. A

committee was formed, headed by M. Sauvan (mayor of

Nice), Albert Gautier (president of the Comité Général

des Sports) and Juste Fernandez (president of the

Aéro-Club de Nice). Like at several other French

meetings, the sporting matters were handled by Marquis de

Kergariou, Paul Rousseau and Ernest Zens from the

Aéro-Club de France. Among the famous people visiting the

meeting were the kings of Sweden and Denmark. US

president Roosevelt was invited, but couldn't take

part.

The budget for the meeting was no less than 800,000

francs, a large part of it provided by the town of Nice.

An enormous lot of work was required in order to make an

airfield of the wet beach flats. Construction of the

airfield installations was delayed by rainy weather and

during the last week preparations were going on around

the clock, in the light of acetylene lamps during the

nights. Sixteen hangars were built, several big

grandstands and a music pavilion, apparently modelled on

the famous casino pier on Promenade Anglais. The price

fund was 215,000 francs. Thirteen flyers entered:

- Charles van den Born (Farman-Gnôme)

- Jorge Chávez (Farman-Gnôme)

- Arthur Duray (Farman-ENV)

- Michel Efimoff (Farman-Gnôme)

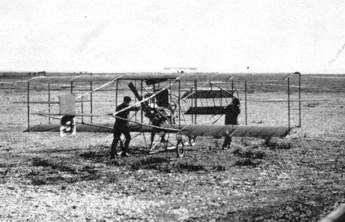

- Hans Grade (Grade)

- Hubert Latham (Antoinette)

- René Métrot (Voisin-ENV)

- Jan Olieslagers (Blériot-Anzani)

- Alfred Rawlinson (Farman-Darracq)

- Frederick van Riemsdijk (Curtiss)

- Charles Rolls (Wright)

- Henri Rougier (Voisin-ENV)

- Robert Svendsen (Voisin-Gnôme)

The unfortunate Hubert Le Blon had also entered, but

he was killed when crashing into the harbour of San

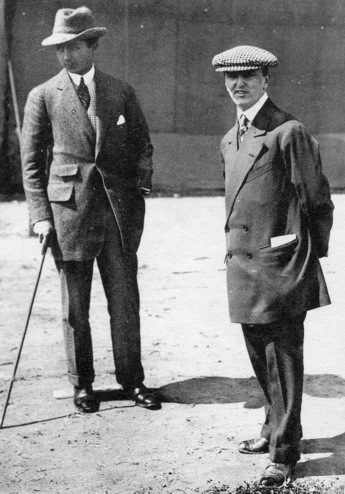

Sebastián on 2 April. The big names were the experienced

Latham and Rougier, but Chávez, Métrot and Olieslagers

were also recognized as rising stars. For Efimoff

(Russia), Rawlinson and Rolls (Britain) and Svendsen

(Denmark) it would be the first meeting.

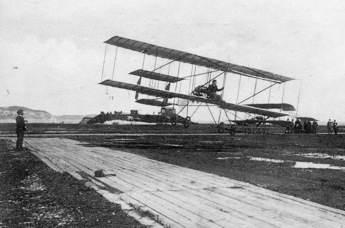

The first planes arrived on the 10th, and by the 13th all

had arrived except Grade's, which was mysteriously

missing en route from Germany. The meeting was preceded

by two further days of bad weather, with high winds and

more rain. During the 13th and 14th the airplanes were

rolled out of their hangars and exhibited to the public,

who paid five francs for seeing them.

Friday April 15th

The first day of the meeting dawned beautifully. The

first to test his wings was Svendsen in his Voisin. He

took off at seven o'clock in the morning, but touched

the ground after a short distance. His main wheels stuck

in the wet sand and brutally stopped the plane. Svendsen

was thrown out of the cockpit, but escaped injury. The

front wheel did its job and prevented the plane from

nosing over, but it took a hard hit and its landing gear

was bent, so the plane had to be towed back to the hangar

for repairs.

Grade's plane finally arrived during the morning,

having been delayed at the railway station of Geneva, and

apart from him everybody was ready except Latham, who had

radiator problems, Duray and Rolls. Rougier and Duray

went for a trip around the course to check the

conditions, but the results can't have been very

encouraging, since the car got stuck in the mud and had

to be helped out. Efimoff and Rougier made short test

flights during around noon.

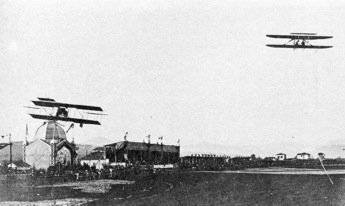

When the official flights started in the afternoon there

was lots of action, and just as at Cannes a Russian flyer

was at the centre of attention. Before the meeting nobody

had heard much about the young Efimoff and he didn't

speak much French, but he turned out to be the star of

the meeting. He was first in the air when the official

flights started at noon and displayed complete control of

his machine, banking steeply around the pylons, zooming

and side-slipping. In total he made at least seven

flights during the day, the longest of 1 hour 16 minutes.

He won the daily four-lap speed prize and take-off

prizes, both with and without passenger, and with 120

kilometres flown he took the lead in the "Prix de la

totalisation des distances".

Chávez made four flights. The first was interrupted by a

broken rudder wire, which he repaired after landing on

the course. His longest flight was 1 hour 22 minutes. Van

den Born made at least two flights, at first taking wide

tentative turns around the tiny triangular course but

soon finding his lines. He made the day's longest

flight, 87 kilometres in 1 hour 40 minutes. Van den Born

was slightly faster than Chávez, gaining gradually and

finally overtaking him, to the excitement of the crowds.

Métrot made a flight of 25 minutes, during which he left

the field and flew over the countryside. Rougier made two

flights of totally 21 minutes. The hairpin turn at the

east end of the course was difficult in the unwieldy

Voisins and both Rougier and Métrot were reprimanded for

flying above the grandstands.

The grandstands were full of nobility and important

persons. At around three o'clock Gustaf V, the king

of Sweden arrived at the field to the tones of the

Swedish national hymn and he had the pleasure of seeing

four planes in the air at the same time, something that

hadn't happened since the Reims meeting the year

before.

Rawlinson made two flights. The first lasted only half a

lap because of engine and rudder problems, but during the

second of eight minutes he flew wide turns over the sea.

Olieslagers made three short flights, troubled by a

sticking valve in his Anzani engine and also being blown

over the grandstands. Svendsen did two more tests in his

repaired plane during the afternoon, but it didn't

run well and he had trouble making turns. He twice landed

close to the waterline. The second time he ran into a

small ravine and had to be retrieved by car. The first

day of the meeting was a complete success, although

several flyers still hadn't made an appearance.

Saturday April 16th

On the second day the weather was more unsettled, with

changing and gusty winds and some rain during the

morning. This did nothing to improve the condition of the

airfield, large parts of which were covered by puddles.

The second pylon could only be reached by planks.

Once again Efimoff was first to make an official flight.

Rain started to fall again and postponed further action

until 13:15. This was the day for the distance contest

and the first to try was Van den Born. He landed after 15

km, breaking a front skid, which was soon repaired. At

13:56 Chavez took off, but his engine didn't run well

and he landed almost immediately. Efimoff flew five laps

and then Van den Born took off again, this time staying

in the air for 58 minutes. At three o'clock Efimoff

was in the air again and immediately posted the best time

of the day for the speed contest, but without improving

his best time of the day before. He didn't land, but

continued until he ran out of fuel at half past four.

Duray made his first flight, after spending some time

finding an obligatory life-vest big enough. He flew the

four laps for the speed contest, but his time was void

since he had failed to announce the flight in advance to

the race committee. Van Riemsdijk also made his first

flight. Olieslagers' engine still didn't run

well, so he failed to take off despite several tries. At

four o'clock the wind had dropped and Rougier took

off. He didn't go onto the course but stayed high

above the sea, around 300 metres off the beach.

At 16:46 Duray and Van den Born appeared to be heading to

a mid-air collision when they tried to round the second

pylon at low altitude at the same time. Duray saved them

by quickly turning right towards the sea. Olieslagers had

finally cured his engine problems and made a flight of 34

minutes at an altitude of 60-80 metres. The tight turns

were difficult for the Blériot pilot, since the wings and

fuselage blocked the view downwards. Due to several pylon

cuts he was only credited with an official distance of

eight kilometres flown.

Chávez and the indefatigable Efimoff took off again,

trying to make use of the last hour before the 18:30

curfew. Efimoff flew more than 138 kilometres during the

day, increasing his big lead over Van den Born in the

"Prix de la totalisation". Latham finally made

his long-awaited first flight but had to land after only

eight minutes. A manometer joint had worked loose and he

was sprayed with hot water. During the short flight he

had already confirmed that the Antoinette was the fastest

plane at the meeting, the lap times of 1:26 - 1:27 being

around ten seconds shorter than those of the Farmans.

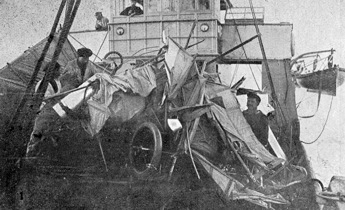

At 17:43 Rawlinson took off and soon found himself in

front of the faster Efimoff, who went to the inside

instead of overtaking high and on the outside as

prescribed. Rawlinson's plane was caught in his

propeller wash and swerved to the right. This drove him

out over the sea and when he tried to quickly get back to

the racing line he lost control and crashed heavily right

on the waterline. He was thrown into the water,

fortunately suffering nothing more than a bruised arm,

but only the tail of the plane remained on the beach

pebbles. The accident happened close to the start-finish

line, so help arrived quickly. The elevator, the lower

wings and the propeller were broken and the engine

drenched, but Rawlinson, after changing to dry clothes

and enjoying a whisky in his hangar to get the taste of

sea-water out of his mouth, hoped that it could be

repaired during the meeting. Efimoff was given a

reprimand by the stewards and fined 100 francs for his

irregular overtaking manoeuvre.

There was still time for a couple of flights. Efimoff

tried for the take-off prizes, winning the non-passenger

prize but not managing to get airborne quickly enough for

the passenger prize. In the last flight of the day Rolls

finally got his Wright into the air, but he returned to

the hangar after half a lap. After the second day Efimoff

led the "Prix de la totalisation" by 269

kilometres against Van den Born's 153 and

Chavez's 125.

Sunday April 17th

The third day started windy, but it didn't discourage

Efimoff who was once again first in the air, only minutes

after the official start, which had been postponed one

hour to one o'clock. Chavez soon followed and he in

turn was followed by Van den Born. There were a couple of

anxious moments when he took off straight onto the racing

line in front of Chávez, but Chávez reacted quickly and

went high to avoid a collision. Van den Born's

mechanics had spent the night replacing the engine, which

suffered from valve problems, but the new one seemed down

on power so Chávez soon overtook him.

When Chávez had flown for an hour and a half his

mechanics started to signal that he should land, but he

kept on. After 1 hour 44 minutes the tank was empty and

the engine stopped. Chávez glided down and made a heavy

landing in a pool of water. He was immediately on his

feet, uninjured but drenched in muddy water, but the

plane was badly damaged. The landing gear, the front

fuselage and the right wings were broken. When asked why

he hadn't landed while the engine ran, Chávez said

that he had wanted to reach the two-hour mark and that he

had trusted that he would be able to glide to safe

landing when he ran out of fuel, but the wind caught

him.

With Van den Born's engine not running well there was

nobody stopping Efimoff from, as usual, taking the speed

prize and the two take-off prizes. For the passenger

prize he had his compatriot Nicolas Popoff, the big money

winner at Cannes, in the passenger seat, his pockets full

of stones to bring him up to the 75 kg minimum weight.

The take-off runs were sensationally short thanks to the

headwind. Olieslagers also made five efforts for the

take-off prize, but his best result of 13.2 metres was

not enough to beat Efimoff's 10.5.

At three o'clock a storm with black clouds and high

winds came down from the north. The wind rose to 12 m/s,

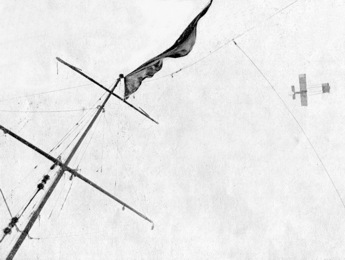

with gusts of 20 m/s. The white flag was hoisted and all

flying stopped. This was no doubt a relief for all flyers

with sick planes, and there were several: Latham's

engine had developed new troubles. Van den Born's new

engine still didn't deliver full power. Métrot's

crew was working on his ENV V-8. Chávez was pleased that

his engine hadn't even received a scratch during the

crash and confident that he could repair his plane during

the meeting. Things looked worse for Rawlinson, whose

plane was completely dismantled.

It would be a long afternoon for the spectators. There

was no action until six o'clock, when the red flag

was briefly hoisted again. Van den Born wanted to fly,

but his engine would have none of it, and then the day

was over. After the success of the first two days this

was a disappointment. Efimoff still led the "Prix de

la totalisation des distances" by 326 km against

Chavez's 203 and Van den Born's 159.

Monday April 18th

The sun was shining again from a cloudless sky, but the

wind from the west was still rather strong when official

flights started at one o'clock. This didn't

discourage Van den Born, who lost only one minute before

taking off, soon followed by Efimoff. The Russian lost

his cap during the take-off, but managed to catch it with

one hand. He then held it between his teeth until the

first turn, where he calmly put it on again! He flew six

laps and took the lead in the daily speed contest, before

landing to make several efforts for the take-off and

passenger contests. Van den Born stayed in the air for 66

minutes, also setting a time for the speed contest. After

landing he only filled his tank before taking off for a

second flight of 69 minutes. When he tried to make a

third start his engine had had enough and a cylinder of

his Gnôme blew off, making a sound like a cannon-shot and

a big hole in the ground where it hit.

At three o'clock Latham took off, but only covered

two laps before his engine started missing. Efimoff, his

confidence obviously sky high, enjoyed himself by making

dives on people along the course. He had already made ten

flights during the day, and more would come.

Around four o'clock there was lots of action on the

airfield. Métrot, who had tried for two days to cure his

engine problems, failed once more to take off. Duray took

off and steered out over the sea, where he circled a

couple of ships and flew along the Promenade des Anglais

before landing. Svendsen took off, but landed after an

uncertain flight of 500 metres. Olieslagers flew a lap,

followed by Rougier and another over-sea flight by Duray.

Rolls took off from his rail and made his longest flight

so far, 11 minutes. His unstable Wright had obvious

problems with the turbulent air and an observer remarked

that his flight looked like a boat rocked by waves.

Olieslagers made several efforts for the take-off prize,

without beating Efimoff's marks, followed by a couple

of laps at 80 to 120 metres. This high flying obviously

spurred Latham, who took off and gradually climbed to 340

metres to the cheers of the enthusiastic crowd. He landed

with his face full of oil from the leaking engine,

stating that the air was very turbulent and that he only

found calm air at 300 metres. Then there was a new loud

bang from the hangars. This time it was one of

Svendsen's cylinders that was blown off, making

another hole in the ground and narrowly missing several

people, among them the king of Sweden.

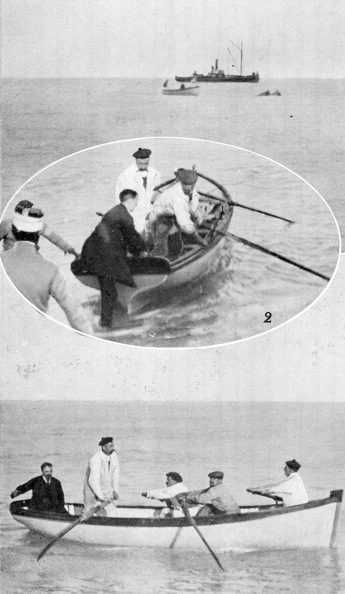

This was not the end of the day's drama. Just before

five o'clock Rougier took off and steered out over

the sea. Around 100 metres off the beach he lost control

of his Voisin, which rolled to the left and dived into

the sea from an altitude of twenty meters. Rougier had

the presence of mind to cut the ignition before hitting

the water, which he claimed felt as hard as concrete. The

plane soon started sinking and Rougier had to fight hard

to get free. He cut his hand on a broken steel wire while

freeing himself from the collapsed fuselage and while

struggling to get to the surface he got a further cut

above the left eye from the wing rigging. It was a narrow

escape, according to the time-takers he had been below

the surface for more than twelve seconds. Rougier was

fortunately a good swimmer and he set off towards the

beach in order to avoid being pulled down by the sinking

plane. He displayed more presence of mind when he first

got rid of his jacket to swim easier and then changed his

mind when he recalled that this would have meant risking

losing his wallet, which contained 10,000 francs in cash,

the entire payment for his appearance in the meeting, his

pilot's license and his insurance documents! He was

soon picked up by a motor-boat and was driven bleeding by

car to the time-keepers' hut on the gun butt inside

the course. The king of Sweden was once again close to

the action and helpfully recommended that Rougier should

change to dry clothes in order to avoid catching

pneumonia. The wreckage of the plane was saved thanks to

a sailor who jumped into the water and managed to tie a

rope to the engine. Since Rougier had a second plane it

was hoped that he would fly again before the end of the

week.

Olieslagers took off immediately after the accident. The

ex-motorcycle racer had experience from nasty crashes and

wanted to give the spectators something to look at that

would take their minds off the dramatic accident. The day

finished with several passenger flights by Efimoff, whose

performance during the meeting exceeded everything that

had been seen before, prompting observers to state that

the days of practical, reliable and predictable flying

had finally arrived. Altogether he carried seven

different friends, VIPs and reporters as passengers

during a day of almost taxi flying. He also increased his

lead in the "Prix de la totalisation des

distances", now 458 km against Van den Born's

266 and Chavez's 203.

Tuesday April 19

This was another sunny day but the winds were

unpredictable during the morning. The only one to venture

out before the official flying started was Grade, whose

machine was finally ready. He made his first test, a

short straight hop, at 12:15.

The first one to venture out after one o'clock was

Van den Born. His mechanics had worked hard to assemble a

good engine from the two failed ones, but three short

tests showed that something was still missing. Back to

work… Meanwhile Efimoff started, as usual regular as

clockwork. He began by clocking four laps for the daily

speed contest and then stayed in the air for almost 50

minutes.

Latham's engine suffered from ignition troubles and

still didn't run well, but that didn't stop him

from reaching 300 metres during a 50-kilometre flight and

winning the daily speed prize with a new course record.

Rolls' Wright was finally in good shape and at 13:35

he started a flight of almost half an hour. After some

quiet minutes almost everybody flew between two and three

o'clock. Van Riemsdijk flew half a lap and landed

after touching the ground with a wing tip, followed by

Duray, who took second in the speed contest. Efimoff made

several efforts at the take-off prize with and without

passengers and as usual won both of them. Van den Born

made another test, but the engine still didn't run

well and he landed after a few minutes. Olieslagers made

two flights, first four laps trying for the speed prize

and then a flight of some twenty minutes, during which he

climbed to 80-100 metres. Rolls made a flight of some

twenty minutes, flying out over the sea. He was forced

down when one of the propellers started breaking up.

Duray, Olieslagers and Grade made further short

flights.

At 15:40 Van den Born came out again, and this time it

appears his carburetion problems were solved. He stayed

in the air for almost 50 minutes, breaking the monotony

of touring the course by venturing out to sea. Efimoff

and Duray made passenger flights.

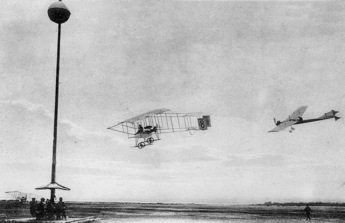

Between four and five o'clock there was another

flurry of activity and for more than twenty minutes the

spectators could watch five planes of four different

makes in the sky at the same time: Latham high,

Olieslagers and Grade a bit lower and Efimoff and Van den

Born chasing laps for the distance contest at low level.

Latham several times frightened the spectators by

stopping his engine to glide down from high altitude, but

it always started again so that he could land under full

control. Olieslagers made a heavy landing and broke a

propeller and a wing tip when a wheel got stuck in the

soft ground, but he would soon be up again in his spare

plane.

Duray, Efimoff and Van den Born took off for the third

"Prix des Passagers", this time a distance

contest. Several of the pilots had started to practice

for the cross-water contests of the upcoming weekend. The

most spectacular sea flight so far was made by Duray, who

disappeared from sight, crossed the Baie des Anges,

turned back at Hotel Beau-Rivage in the Old Town and

returned along the Promenade des Anglais to the

excitement of the around 15,000 people watching.

Olieslagers was out in his spare plane and Grade made an

impressive flight at relatively high altitude. Rolls also

started a flight at around half past five.

At 17:45, after flying several laps, Grade found himself

behind one of the Farmans and since his light plane was

disturbed by the wash he decided to land. When about to

touch down he suddenly noticed a group of people in front

and gunned the engine to pass over them. The plane

bounced high into the air with the nose almost vertical,

jumped the wall that separated the airfield from the

river Var and landed on its nose, luckily on a sand bank

in the middle of the river. Grade was unhurt, but the

accident site was separated from the airfield by a wide

arm of the quickly flowing river. A brave seaman,

identified by three different names in three different

Nice newspapers, finally managed to cross the stream in a

little boat and brought Grade to the hangar area, where

help quickly arrived. Grade had married only a week

before the meeting and this was perhaps not what he

expected from the honeymoon! The plane was retrieved in

the moonlight in the evening with the help an improvised

raft and two strong horses. The propeller and the bamboo

beam forming the rear fuselage were broken, but otherwise

the plane appeared to be easily repairable.

As for the other pilots who had suffered accidents,

Rawlinson still had his arm in a sling and was uncertain

about returning to the action. Chávez's crew and

mechanics from local airplane builders Henri Chazal were

working long busy hours repairing his plane. A reporter

colourfully described a person sitting in the

airplane's seat, which had been placed on top of a

fuel canister, sewing fabric onto the rebuilt wings.

Rougier had made a complete recovery and was following

the flying from the balcony of his hotel room. It was

reported that he had decided to rest from flying for a

month after his busy touring during the spring, but he

would never return to competitive flying and announced

his retirement a couple of weeks later.

Efimoff, Van den Born and Rolls were all still in the air

at 18:30 and had to be flagged down. Van den Born's

mechanics were finally rewarded by seeing him win the

"Prix des Passagers" after a flight of 70

minutes. Efimoff was beaten by a mere four laps, but the

155 kilometres that he had flown during the day had once

again increased his lead in the "Prix de

totalisation". He had now reached 614 kilometres,

which was claimed to be a world record for distance

covered during a single meeting. The previous best was

the 569 kilometres scored by Hubert Latham during the

1909 Reims meeting. Van den Born had reached 276 km and

Chavez 203 km.

Wednesday 20 April

This was a perfect day for flying, with light cloud cover

and winds never higher than 3 m/s. Could the astonishing

success of the previous day be repeated?

Latham and Duray had both protested to the race committee

that they had been hindered by slower planes during their

efforts for the Prix du Tour de Piste the day before.

Duray, who had a strong engine in his Farman, even had to

overtake two planes during one of his flights and landed

after three laps to make his protest.

As usual Van den Born and Efimoff were first out, only

minutes after one o'clock. Both made efforts for the

Prix du Tour de Piste and then went on to collect

"frequent flyer miles". Rolls started at 13:36,

also with the same strategy. Speeds were improving, no

doubt as pilots learned the best lines around the tight

turns of the short course. Rolls displayed the

manoeuvring capabilities of the Wright by swooping from

high altitude and flying small circles over the Var.

After two days and nights of hard work after the Sunday

crash Chavez's Farman was ready to fly at 14:08. New

smaller lower wing panels had replaced the original

equal-span wings, which seemed to improve the speed.

Despite a troublesome engine he posted the best time for

the "Prix du Tour de Piste". His lead

didn't last long, however, since Latham soon posted a

record-beating 5:38.8, but it was the best time by a

Farman, beating Duray's time of the day before.

Efimoff made a short break to fill his tank and let the

engine cool down before taking off again. Chavez started

a second flight at 15:15 and covered five laps before

retiring for the day because of engine problems. Latham

took off for a twenty-minute flight, flying high and

above the countryside. Meanwhile, Efimoff made another

landing and took off again. At 15:37 Rolls took off,

having changed propellers. He made two flights, totalling

more than an hour and officially covering 54 kilometres,

despite touring over the sea and having to cut pylons in

order to avoid hindering other planes.

Around four o'clock Métrot finally rolled out his

Voisin after trying for a couple of days to make his

engine run well. The mechanics had apparently been

successful, because he immediately embarked on a

spectacular high flight, eventually reaching 340 metres.

Latham obviously felt that this was a challenge to his

territory and climbed to 250 metres while Métrot made a

quick descent and an elegant landing in front of the

grandstands. Latham stayed in the air for more than an

hour, covering 57 kilometres. The altitude contest would

be held on the next day and Efimoff, who had previously

hardly flown higher than the pylon tops obviously wanted

to play too. He quickly climbed to 175 metres before

landing again, perhaps not wanting to show his hand.

Duray, Efimoff and Olieslagers made efforts for the

take-off contest, but the outcome was the usual: Efimoff

won both with and without passenger. This was the day for

the "Prix des Mecaniciens", a contest of one

lap with standing start. Duray and Efimoff made two

efforts each, with Duray scoring the two best times.

Latham had also entered, but the place where he was

instructed to start was wet and muddy and his wheels got

stuck. The plane started to nose over but was caught by

the nose skid, which dug deeply into the ground. The

propeller hit the ground and broke. As could well be

imagined, Latham was furious and protested to the race

committee for forcing him start in such a bad place. The

damages were fortunately restricted to the propeller and

the nose skid, so after replacing those he would be able

to compete for the altitude prize the day after.

Efimoff and Rolls finished the day's flying. Efimoff,

who again had to be flagged down after the curfew, had

flown 135 kilometres during the day, yet again increasing

his lead in the "Prix de Totalisation". The top

five at the end of the day were Efimoff (750 km), Van den

Born (411 km), Chávez (246 km), Latham (184 km) and Rolls

(157 km).

The organizing committee announced that unawarded prize

money would go towards a "Prix de Mérite" for

the three flyers who had contributed most to the success

of the meeting. They also announced that since the

exhibition of airplanes before the start of the meeting

had been hampered by rain and wind there would be a

similar exhibition on two more afternoons.

Thursday 21 April

The weather was again perfect on the sixth day of the

meeting. The main event of the day would be the

"Prix de l'Altitude", which many in the

crowd regarded as the most exciting event. Endurance

isn't so exciting to watch, and the speeds of around

60-70 km/h were not that mind-blowing, but flying at an

altitude of several hundred meters! In the absence of

world record holder Louis Paulhan everybody expected

Latham in his beautiful Antoinette to win it. Would he

succeed? Paulhan had after all flown a Farman when he set

the record, but Latham had also reached 1,000 metres

before…

Before the start of the day's action the local

restaurant owner M. Roux invited all the flyers for a

five-course luncheon. This was perhaps the reason why

despite the perfect conditions nobody tried their wings

until Latham brought out his plane at 13:35. This flight

could have robbed him of the chance to win the "Prix

de l'Altitude": His landing after a fast six-lap

flight was heavy and just as the day before the main

wheels stuck in the soft ground, the tail started to rise

and the front skid dug in. Fortunately only the propeller

was damaged, but now Latham only had one left. While

Latham flew Rolls took off and made a flight of more than

an hour, setting a time for the "Prix de Tour de

Piste" and making a couple of tours over the

sea.

Duray made three starts, but his engine kept missing and

he never flew more than a single lap. After a quiet

interval Efimoff took off at 15:06 and beat Rolls'

time at the start of a 23-minute flight. Rolls made a

second short flight, then Efimoff tried without success

to improve his time for the "Prix de Tour de

Piste" before once again winning the two "Prix

de Lancement". His passenger was the young wife of a

local press man, who completely enjoyed the experience,

saying it was better than riding a car. For his next

passenger flight he brought General Beaudenom de Lamaze,

commander of the 29th Division, who stated he felt

totally secure during the flight.

Flights for the "Prix de l'Altitude" were

supposed to start at four o'clock, but nobody wanted

to be first. In the end Chávez took off at 16:38,

followed four minutes later by Latham. Chávez circled

ever higher, but Latham's Antoinette climbed faster

and after seven minutes he passed Chávez's Farman at

200 metres and quickly pulled away. Latham had reached

490 metres when a belt broke and the crowds immediately

heard the engine losing power. He quickly pointed the

nose downwards and at 17:15 glided to safe landing,

helped somewhat by the two cylinders that still fired.

Frantic action started in the Antoinette hangar, while

Chávez kept climbing, finally reaching an unofficially

measured 660 metres after a 49-minute climb. He landed at

17:45 after a 67-minute flight, hoping that he had done

enough. He didn't know how high he had been, since

his altimeter only went to 600 metres.

At 17:10 Métrot took off for his effort. He used a

different strategy, making only two wide circles instead

of the many tighter circles of Chávez and Latham. He

reached 235 metres before finding the turbulence too

difficult and abandoning his effort. He went on a tour

over the countryside and the city centre, returning along

the beach promenade to land after 30 minutes. At 17:23

Van den Born took "Le Figaro" reporter Frantz

Reichel for a 15-minute flight. This was the first

passenger flight over the sea and they also finished with

a tour along the promenade and around the airfield.

At 17:30 Efimoff started the engine in order to go for

the "Prix de l'Altitude", but he had hardly

started rolling when a loud bang was heard and his

propeller disintegrated, miraculously without injuring

anybody. Somebody had left a tool on one of the lower

wings and when the plane started moving it fell into the

spinning propeller. There wasn't time for both

replacing the propeller and reaching a competitive

altitude, so Efimoff was out. Rolls also took off at

17:30, climbing to 235 metres before giving up and

landing after 12 minutes. Olieslagers took off at 17:50

and reached 220 meters during three wide tours of the

field before coming down to land.

Latham took off at 17:48 when the broken belt had been

replaced. He climbed quickly, but would he have time to

get high enough in the 42 minutes remaining before the

18:30 curfew? His last lap had to be cut short in order

to pass the line before the deadline and just as the

cannon-shot announced the end of the day the stewards

indicated that he had also unofficially reached 660

metres. Would it be a dead heat? The race committee would

check their measurements before announcing the final

results.

While Latham flew, several other planes were in the air.

Van Riemsdijk, who hadn't flown before during the

day, made a flight of one lap and Grade took out his

repaired monoplane for a two-lap flight. Rolls, Van den

Born, Chávez and Olieslagers all added some laps to their

scores for the "Prix de Totalisation". The top

five at the end of the day were Efimoff (818 km), Van den

Born (433 km), Chávez (286 km), Latham (227 km) and Rolls

(222 km).

Shortly before eight o'clock the official results of

the "Prix de l'Altitude" were finally

announced: Latham had won by a mere twelve metres, the

official results being 656 metres against 644! Chávez

accepted the disappointing decision sportingly and took

the opportunity to thank Van den Born for lending him

some engine parts that had made it possible for him to

fly at all. Small adjustments were also made to the

results of the other three pilots, resulting in Rolls

being elevated to third place. Efimoff announced that he

would try to beat the world altitude record the day

after.

On the following day Latham filed an official protest to

the race committee, accompanied by the required fee of 50

francs. He had heard from one of the stewards that the

margin of error of the measurements was bigger than one

percent, which meant that it wasn't certain that the

results really reflected reality. Latham stated that

since he would himself find it very unpleasant to be the

victim of such circumstances, and being the only one to

have anything to lose, he wanted the results to be

modified taking into account the risk of errors. As a

consequence he would be willing to share the prize money

with Chávez. The committee rejected the protest, simply

stating that the contestants had no right to question the

means employed by the committee for measuring the

results. On such matters the committee was only

responsible to the F.A.I. and the "Commission

Aérienne Mixte".

Friday 22 April

This was the last day of the regular contests, since the

weekend would be devoted to the two over-water

cross-country races. During the morning Van den

Born's mechanics installed a new engine to replace

his previous troublesome example, a work which was

accomplished in two hours. Rawlinson's plane was now

completely repaired, except that he still hadn't

received the propeller, which was being sent by railway

from Paris. Svendsen's hangar was empty. He had

packed his plane and would leave during the afternoon,

probably realizing that he was not ready for meetings

like this. Métrot was also disassembling one of his

planes in order to send it to the upcoming meeting in

Tours. He would not make any flights during the day,

since he still didn't trust his engine.

The weather had turned worse, with strong winds from the

east and dark clouds, and the crowds were not as numerous

as the previous days. The reports in the local newspapers

were not so enthusiastic anymore and some remarked that

the endless flying was not very interesting. Immediately

after the official start at one o'clock Efimoff was

in the air, flying four fast laps for the "Tour de

Piste" contest, followed by a flight of some 50 km.

Chávez, Latham, Van den Born and Rolls followed the same

agenda. Efimoff was far ahead in the total distance

contest, but the others were still fighting for

positions.

Soon after two o'clock Latham made an effort for the

"Prix de tour de piste", easily beating the

previously best time of Efimoff. Around three o'clock

Efimoff made his daily efforts for the take-off prizes,

as usual winning both. Then he made a second effort at

the "Tour de Piste", but the result was no

improvement. Afterwards he returned to the hangar to let

his mechanics check the engine, which he felt didn't

perform well, perhaps an effect of the propeller incident

the day before. Grade in his "flying hammock"

made several short flights in the hard wind, obviously

taking no risks. Around 15:15 several pilots made new

efforts for the "Prix de tour de piste". Van

den Born was first and took the lead. He was followed by

Duray, who beat him by four tenths of a second. Then

Latham, despite the presence of three other planes around

the course, posted a time of 5:41.8, way beyond the

capability of the Farmans. Rolls also flew the four laps,

even though his Wright had no chance in a speed

contest.

At 17:20 Efimoff took off for his promised attack on the

world altitude record, held at 1,269 metres by Louis

Paulhan since the January Los Angeles meeting. He climbed

quickly in large circles to an altitude of 250 metres,

followed by everybody's eyes, but then his engine

started to miss and suddenly stopped. He was far out over

the sea when it failed, but managed to restart the engine

a couple of times and glide down to a safe landing on the

beach, only metres from the waterline. If the failure had

occurred just seconds earlier he had been in for a bath.

This put an end to his flying for the day, but the 887

kilometres that he had flown during the eight days had

already secured the win in the "Prix de

totalisation" by a broad margin.

Latham and Van den Born were still flying lap after lap,

the latter covering a total of 151 km during the day,

which put him in a safe second place. Latham's 91 km

was not enough to demote Chávez from the third place, but

forced him to make an extra flight during the last half

hour of the day. This was made with one of his mechanics

as passenger and his times over 15 km (16:31.0) and 25 km

(25:26.4) were claimed as speed records with

passenger.

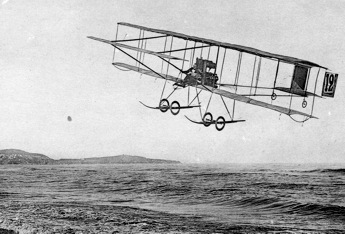

Saturday 23 April

The big event of the day was the "cruise" from

the airfield across the Baie des Anges, around the

lighthouse on Cap-Ferrat around six kilometres south-east

of the centre of Nice and back. It was, somewhat

questionably, announced as the first race of its kind,

perhaps based on the fact that at the similar race held

at Cannes three weeks earlier only one competitor had

completed the course. In order to ensure that all flying

around the course was made in the normal anti-clockwise

direction the flyers had to cross the start/finish line

and then round all three pylons before turning towards

the sea. At the finish they also had to round all three

pylons before crossing the line. Flights were allowed

between three o'clock and half past six.

Eight of the flyers announced that they would

participate, while Olieslagers, Grade and Rawlinson

wouldn't. Olieslagers didn't think his light

low-powered Blériot would have a chance. Grade's

propeller shaft had been bent during his crash in the

Var, which made the bearings overheat and limited him to

short flights. Rawlinson had found out that some of his

struts had warped as a result of being dipped in the

water during his crash, and his arm was still in a

sling.

The destroyer "Carabinier" and four French navy

torpedo boats would be stationed along the course, and

several other steamers and motorboats would also be ready

to quickly help flyers who had to ditch. Efimoff, Chávez

and Rolls had made a reconnaissance cruise along the

course aboard the "Carabinier" during the

morning. Rolls and Van Riemsdijk had fitted flotation

bags to their planes. At noon M. Sauvan, mayor of Nice,

offered a five-course luncheon to the race committee and

all the stewards. Crowds estimated at 60,000 to 100,000

spectators lined the airfield and the beaches and

quays.

The first flyer to take off was Duray, but since he would

have jumped the gun he was flagged down by his mechanics

for a new start. Therefore it was Van den Born who was

first out on the course at 15:01, followed exactly one

minute later by Duray. They were followed by Latham at

15:13, visibly faster, and twenty seconds later by Rolls,

who flew much higher than the others. Chávez started at

15:18 and also flew very high. He had flown an extra lap

around the course before starting in order to climb to an

altitude where he felt he would be able to safely glide

close to a ship if his engine failed over sea.

Duray, in his faster machine, overtook Van den Born at

the end of the first leg. Even after losing time with a

wide turn at the lighthouse he was ahead coming back to

the airfield, but he made another bad turn returning to

the airfield and at 15:20 the planes crossed the line

almost at the same time. They both said that there had

been no problems, except that on the return leg, flying

towards the sun, the haze had made it difficult to see

ahead. At 15:30 Latham landed, easily beating the two

Farman pilots with a flight averaging 86 km/h. He was

followed almost five minutes later by Rolls, who declared

that he would make a second effort when the wind

decreased. Chavez landed at 15:35, but his time was only

good enough to beat Rolls. Efimoff was next to start at

15:46. He narrowly beat Chávez but was not satisfied with

his time. Métrot made his start at 16:20. His Voisin

didn't have the speed to compete for the price money

and he flew high and close to the coastline. At 17:08

Efimoff started a second effort, but he had to turn back

halfway on the first leg when his engine started

missing.

Both the race committee and his friends tried to

discourage Van Riemsdijk from flying over the sea, since

his engine didn't run well, but the young Dutchman

didn't want to listen and at 17:18 he made his start.

Already after four kilometres, two kilometres from the

beach, he was in trouble. The engine ran very irregularly

and the machine flew erratically, even touching the water

a couple of times. The "Carabinier" and one of

the torpedo boats speeded towards the crippled plane and

when it finally ditched they were able to quickly rescue

Van Riemsdijk, who was waving to signal that he was all

right. Two boats were launched and fished him out of the

water. Well on board one of the torpedo boats he shouted

instructions to the seamen that they should tie ropes to

the engine of the plane, so that the fragile airframe

wouldn't be damaged. The whole rescue operation took

less than four minutes and the tug "Polyphème"

retrieved the damaged plane soon afterwards. Van

Riemsdijk was bought to the harbour of Nice, where he

thanked his rescuers. He calmly asked for a cigarette and

declared that he wanted to take another bath, unforced

this time, and change clothes, so that he could return

those that the captain of torpedo boat No. 203 had lent

him.

At 17:30 Rolls made his second effort and the lighter

wind and his experience of the course enabled him to

improve his time by some four minutes and beat Duray to

the second prize - it seemed... The next day the race

committee announced that there had been an error in the

timing and that his time was two minutes longer than

originally announced, only good enough for fourth. While

all this was going on, Grade, Olieslagers and Duray made

some short flights around the airfield. Van den Born sold

five passenger flights around the course for 100 francs

each, donating the money to a local campaign for a

monument over the late Ferdinand Ferber, who made several

of his flying experiments very close to the airfield.

It was announced that the meeting would be extended by

one day. On the Monday the pilots could compete for

additional prizes for altitude and total distance, and

the ticket prices would be halved. It was declared a

holiday for the 2,000 children of the schools of Nice and

special trains would carry them to the airfield free of

charge.

Sunday 24 April

This last day of the official meeting dawn beautifully,

with clear sky, a light mist over the sea and almost no

wind. The event of the day would be the over-water race

from the airport to the Garoupe lighthouse at Antibes and

back. When the program for the meeting was first

published it included the option of extending this race

to Cannes and back, but in the end the shorter distance

was chosen. Duray and Van den Born had taken the

precaution of making a car trip to Antibes in order to

have a look at the turning point. A second destroyer, the

"Mousqueton", had joined the fleet of different

craft patrolling.

From the hangars came the news that Efimoff's

mechanics had replaced his all but worn out Gnôme rotary

with a stronger 60 hp ENV V-8. Van den Born had decided

not to participate in the race, since he reckoned he

would have no chance against Latham's Antoinette and

the Farmans with stronger engines than his Gnôme, and he

had other plans, which he didn't announce yet... The

King of Denmark had arrived and joined his Swedish

colleague in the reserved grandstand.

When the official flying started the pilots wasted no

time. Rolls had flown a couple of laps around the course

waiting for the cannon that announced the start and cut

the start line five seconds past three. He was followed 5

seconds later by Chávez and after 20 more seconds by

Latham. En route to Antibes Latham passed both Chávez and

Rolls, thereby winning the prize offered by the town of

Antibes to the flyer who would first turn around the

lighthouse. He passed it at around sixty meters, waving

to the spectators, before disappearing into the mist

again. Rolls won the second prize over Chávez by only

five seconds.

Latham returned to the airfield taking a slight detour

along the coast, posting a time of 20:16.0, which would

stand as the best of the day. Chávez overtook Rolls on

the way home and both landed safely. Latham didn't

land but flew a lap of the course and then immediately

set out on a second flight to Antibes. The second time

was no improvement, but after landing the celebrations

were enormous and he and his mother were taken to the

official tribune, where he was presented to the kings of

Sweden and Denmark.

At 15:40 Métrot took off in his Voisin. He knew that all

the other planes were faster, so he flew a wide high

course and returned safely to the airfield, posting the

slowest time. He was probably looking forward to the

Tours meeting the next weekend, where he would fly the

new "racing type" Voisin. Duray took off at

four o'clock and posted the second best time, of

21:40.4, as usual flying at minimum altitude. During the

afternoon Olieslagers flew several laps around the

airfield and at five o'clock decided to give the

citizens of Nice something to look at by making a long

flight over the city centre, passing the promenade and

the Casino and circling the Place Massena.

At 16:20 Efimoff flew several laps of the course in order

to verify that his new engine installation was in order.

He was followed five minutes later by Chávez, who made

his second cruise. This time Chávez, probably realizing

that he too had no chance of beating Latham or the

ENV-engined Farmans, went for high altitudes. He passed

the lighthouse at 350 metres before climbing to an

estimated 600 metres during the return leg. After some

adjustments Efimoff finally set off at 17:10. He beat

Duray's time by some nine seconds.

Van den Born did not participate in the contest, but at

17:15 he declared that he would instead fly to Monaco and

back. The race committee tried to discourage him,

pointing out that his flight would be in the opposite

direction of the race and that there would be no boats

patrolling his course to pick him up if he fell into the

sea. Van den Born refused to change his plans and set

off, while telephone calls were made to places along his

way to try to find people who could offer help if he was

forced down. After a flight of 38:30 he was back, to the

relief of his wife and everybody else. He stated that he

had had no problems and that he had turned back at the

Oceanographic Museum of Monaco, where there had been some

turbulence.

At 17:22 Rolls made a second effort around the Garoupe,

without improvement, and without landing set off for a

third effort, this time improving his time somewhat. At

six o'clock Efimoff made a second effort. This time

his engine was running better and he came within 28

seconds of Latham's time, beating Duray to the second

place.

At six o'clock Latham took off for a third attempt at

the "cruise". When he hadn't been spotted

from the airfield after fifteen minutes and it was noted

that the two destroyers had turned towards Antibes at

full steam it was realized that he had ditched. Around

400 metres from the lighthouse his propeller had broken,

forcing him to glide to a safe but wet landing. One of

the torpedo boats was first to reach Latham's

floating plane and found him calmly smoking a cigarette,

unharmed but wet to the knees. A dinghy picked him up,

but he gave instructions to tow the plane to the Antibes

harbour rather than try to lift it aboard. The rescue was

signalled to the airfield, where Latham's mother was

relieved to get the news. Including his two failed

attempts to cross the English Channel this was the third

time he had ditched a plane!

Towards the end of the day Duray, Chávez and Efimoff made

several passenger flights, giving a general, some V.I.P.s

and reporters and a couple of Russians royalties their

first flights. The day was finished with a six-course

dinner with fine wines, offered to the flyers by the city

of Nice.

Monday 25 April

Two contests, for total flying time and for altitude, had

been announced for this extra day, which started by a

luncheon at the Roux restaurant for the race committee

and several V.I.P.s together with three of the flyers.

However, the feared mistral struck with winds of up to 20

m/s. No flights were possible and all the school-children

who had been granted a day off to visit the races had to

go home disappointed, having only seen some planes in

their hangars. They particularly didn't get to see

their hero Latham or his plane, since the Antoinette was

disassembled for shipping at Antibes. Rawlinson and

Efimoff kept their machines ready until the end of the

day in case weather improved, but to no avail.

Latham and the "Club Nautique de Nice" had

planned to use the Monday for making the experiment of

using an airplane for reconnaissance over the sea. Latham

would be sent out to look for an "enemy" ship

(the "Carabinier") and signal its position by

dropping a coloured sheet of paper. A red paper would

indicate that the enemy ship was to the west and a blue

paper that it was to the east. A white paper would

indicate that the enemy was already in the bay, and in

that case Latham would indicate the direction by pointing

his plane in that direction. This "very

interesting" experiment was of course stopped by the

wind and by Latham's accident the day before.

Although Efimoff stayed for another day of several

passenger flights the travelling circus quickly packed

their planes to go to the next event - Chávez, Métrot and

Duray to Tours, Latham and Van den Born to Lyon,

Olieslagers to Barcelona, Van Riemsdijk to Palermo and

Grade to Berlin.

Conclusion

The 1910 Nice meeting was a complete success, thanks to

the combination of good weather, competent organization

and several pilots who really wanted to fly as much as

possible. The total distance of the officially recorded

flights was announced as 3,265 kilometres, which by quite

a margin beat the previous highest distance flown during

a meeting, the 2,462 kilometres flown during the 1909

Reims meeting.

Efimoff had flown a total of 960 official kilometres,

which at 60 km/h corresponds to a total flying time of

sixteen hours - not counting his many unofficial flights.

The ever-smiling Russian with his amusing, enthusiastic

but very broken French was the surprise hero of the

meeting, while Latham, the "king of the air",

didn't disappoint his many followers. Van den Born

and Chávez also marked themselves out as competent

pilots, the latter building his reputation as an

high-altitude expert. The dozens of passenger flights

performed during the meeting without incident was also

remarkable.

The small airfield with its short 1.5 kilometre course

with a hairpin turn at one end was criticised by some

pilots and certainly handicapped planes that weren't

manoeuverable enough. Despite the large amounts of money

invested in preparing the airfield it was wet and uneven

in many places. The proximity to the sea was of course

exciting and provided a good view for the spectators, but

six planes ditched and it was lucky that only two pilots

were lightly injured.

The meeting cost enormous sums to organize, and already

while it was going on was predicted that the losses would

be big, but since the Californie airfield is still in

operation it was perhaps a wise decision by the town of

Nice to invest the money.

Back to the top of

the page

Back to the top of

the page