Reims, France, July 3rd - 10th, 1910

The biggest aviation meeting before the Great War

The 1909 "Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la

Champagne" was a huge success and a defining event

in the history of aviation. Plans for a follow-up event

started immediately after it ended and an organizing

committee created. The date for the meeting was decided

by a meeting of Federation Aeronautique Internationale on

January 10th, and wheels were set in motion to create an

aviation meeting that would surpass everything of its

kind.

Everything at the airfield had to be built from scratch

again, since the temporary installations used at the 1909

had been dismantled immediately after that meeting. The

main grandstands were built in approximately the same

position as the year before, only a little to the south,

but everything else was realigned. The hangar area was

enlarged and moved further to the northwest, closer to

the main road. The 1909 rectangular ten-kilometre course,

which had been criticized because too large parts of it

weren't visible to the public, was abandoned in

favour of a shorter five-kilometre course. This took less

than half the space and was more visible to the

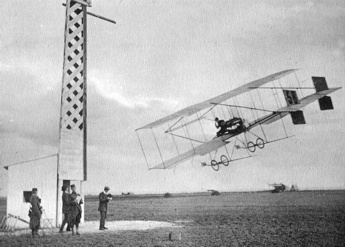

spectators. The new course had six pylons, with two

90-degree turns and four 45-degree turns.

There were no participants from either Britain or the

United States, but despite this, 76 machines were

entered. They represented 14 different makes, but in the

end no machines from Wright, Tellier or Maurice Farman

would turn up. The most popular make was Henry Farman

with 14 entrants, followed by Blériot (12), Sommer (9),

Antoinette (8) and Voisin (8). Machines from Nieuport,

Sanchez-Besa and Pischof (called "Werner" in

the official program, after the manufacturers Werner &

Pfleiderer) would appear for the first time at a French

meeting.

Just like the year before, the Champagne manufacturers

made big contributions to the prize funds. A total of

more than 200,000 francs would be given to the winners.

There were a couple of novel contests. The biggest prize,

a single prize of 50,000 francs, was the "Grand Prix

de Champagne". It would be won the manufacturer

whose three best machines had flown the longest total

distance during the week. Another novelty was the

"Prix de Totalisation des Hauteurs", which

would be won by the pilot with the highest sum of

altitudes reached during any number of officially

controlled flights. The "Prix Michel Ephrussi",

named after its sponsor, a banker and breeder and racer

of thoroughbreds, was the first air race ever in which

the machines were released side by side at the same time,

in race-horse style. It was held over a cross-country

course of 22.4 kilometres. There was also a contest for

military kites.

Sunday 3 July

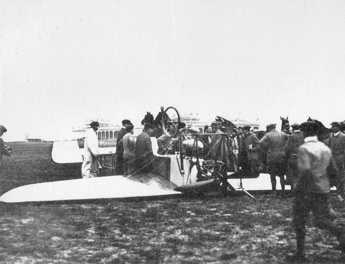

The first day of the meeting was windy. During the late

morning it started to rain, a fine persistent rain that

was interrupted from time to time by heavy showers. The

official flights started at eleven o'clock and at

11:11 Charles Wachter was first to take off in his

Antoinette. The wind was recorded as 12 m/s, and it made

him miss a couple of pylons on the first lap, but after

these initial struggles he went on to fly nine good laps

during a flight of 43 minutes. After Wachter's

landing, Farman pilot Charles Weymann took off, but he

landed after a single lap due to the torrential rain.

After noon René Labouchère took off in his Antoinette,

followed by Weymann. Labouchère went on to fly seven laps

in 32 minutes, while Weymann gave up fighting his

machine, which was pitching up and down, after three laps

and turned inside the course to land. He almost

immediately took off again, but again landed after only

half a lap.

At 14:13 Walther de Mumm in his Antoinette tried to take

off, but for some reason landed at the foot of the first

pylon and returned to his hangar. At three o'clock he

took off again and quickly climbed to 150 metres. He was

followed by fellow Antoinette pilot Hubert Latham, who

was driven far off the first pylon by the wind, but

returned to the course and landed after a well-controlled

16-minute three-lap flight. Weymann made his third start

at 15:15, also deflected by the wind at the first pylon.

He climbed to 20 metres before diving steeply to almost

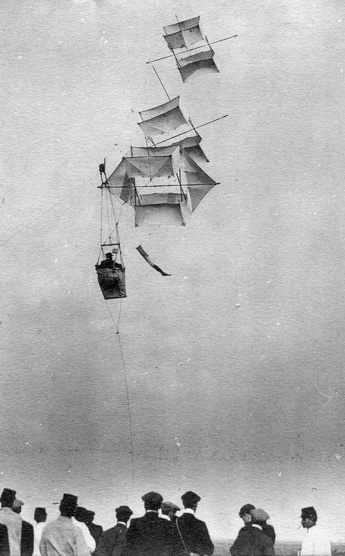

ground level. During their flights Capitaine Madiot was

launched, standing in his balloon-type wicker basket

lifted by a train of four kites. The landing after his

short flight was heavy, but there were no damages.

Then a series of flights started, with Léon Morane first

to take off at 15:40, having trouble to take the pylons

accurately in the wind in his light Blériot. Robert

Martinet, in his heavier Farman, managed to make tighter

turns. The relatively unexperienced René Thomas, in the

fourth of the factory Antoinettes, lost control during

his take off and put the machine on its nose. At four

o'clock Wachter took off again, followed by Léon

Cheuret, Jules Fischer and Weymann, their three Farmans

framed by a rainbow. Jean Daillens took off on his Sommer

and then Charles Van den Born made it four Farmans in the

air, climbing to some 500 metres.

The winds had decreased a bit and several engines were

heard from the hangars. Étienne Bunau-Varilla and Henri

Brégi on Voisins, Marcel Hanriot on one of the monoplanes

of his father's make, Otto Lindpaintner on a Sommer,

Nicolas Kinet and Joseph Christiaens on Farmans, both of

the large-span model, and Jan Olieslagers on his Blériot

made for an interesting mixture of airframes and engines

in the air. There were now twelve or thirteen machines

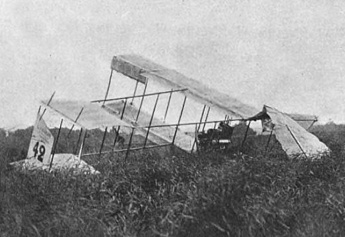

circling around the five-kilometre course. Brégi's

flight ended with his machine upside down in an unmowed

field before he had recorded any official result, but

obviously without injuries. Maurice Tétard took off,

while Bunau-Varilla and Van den Born landed. Some

improvised races started to appear, particularly between

Wachter and the chasing Olieslagers.

The reporters had by now more or less given up reporting

the flights in any detail. They were probably as

overwhelmed as the timing staff, who after the first day

would give up recording exact flying distances and

instead only count whole laps. De Mumm, Louis Wagner and

Michel Efimoff took off, despite a huge, threatening

cloud that towered over the airfield. After a while the

weather improved, and more pilots took to the air,

circling "like flies around a lump of sugar"

according to the reporter from "Le Figaro". The

reporter from "L'Auto" claimed that it was

"as crowded at 30 metres as in the Rue de la Paix at

five o'clock in the afternoon", forcing Latham

to climb to the less busy altitude of 300 metres.

"Baroness" Raymonde de Laroche also took off,

leaving the airfield to fly above a train on the nearby

railway. Morane and Latham competed for the daily

altitude prize, which started at four o'clock and

which Morane eventually won by reaching 862 metres.

Around six o'clock there were only three or four

pilots still in the air. One of them was Wachter, who had

already flown 142 kilometres in his Antoinette, the

longest total distance of the day. He had started to

descend from an altitude of around 200 metres above the

fourth pylon, close to the Modelin farm, when his machine

suddenly pitched down and fell like a stone to the

ground, followed by its wings, which had folded upwards,

departed from the fuselage and slowly fluttered down in

zigzag. The onlookers screamed in horror, while the

ambulance services quickly rushed to the accident site,

but there was no hope. Wachter had been killed

immediately by the impact, suffering multiple fractures

and massive injuries to the head, back and chest. The sad

news had to be brought to his wife and his daughter of

five years, who had accompanied him to the meeting, and

to his brother-in-law Léon Levavasseur, the designer of

the Antoinettes. The structural failure of the machine

was blamed on Wachter over-speeding when descending to

land without cutting the engine, but the machine had made

five flights that day, in rain and hard winds, and it is

quite likely that the rigging had got loose.

Wachter, who was 36 years old, had worked as a mechanic

for Antoinettefor several years, particularly on racing

boat engines. He had only started flying two months

before the meeting, but had already made himself a name

as a daring and competent pilot and a popular instructor

at the Antoinette flying school. He became the

world's eighth pilot to die in a flying accident. The

accident put an end to the days' flying, except for

Efimoff, who made a last flight and was criticised for

"flying above the corpse of his comrade".

Until the accident the meeting had delivered an

unprecedented flying experience, despite the difficult

weather conditions. Altogether 24 pilots had flown during

the first day. Tétard's flight of 87.125 kilometres

had beaten Olieslagers to the prize for the day's

longest non-stop flight. Weymann was second in the daily

total distance contest after the unfortunate Wachter, his

139.750 kilometres beaten by less than three

kilometres.

Monday 4 July

The second day also started windy, but Émile Ladougne in

his Goupy biplane, Alphonse de Ridder in his Farman and

Bunau-Varilla made test flights between ten and eleven

o'clock. When official flights started at noon,

Lindpaintner was first in the air. He was followed by de

Mumm, Olieslagers, André Bouvier (Sommer) and Van den

Born, but because of the increasing wind all of them

landed soon. Olieslagers' flight of 20 kilometres in

17 minutes was the longest. Capitaine Madiot, however,

found the high winds more useful to test his kite

train.

When everybody had landed there was no action on the

airfield until three o'clock, when Weymann started

the engine of his Farman, but he decided that it was

still too windy and never left the ground. The other kite

train, of Lieutenant Basset, was also tested. Around half

past four the weather turned even worse, with a violent

wind from the north and dark threatening clouds. A window

pane in the press pavilion was broken by a gust, and

those who had hangars facing to the north started

worrying about their integrity.

The weather improved towards the end of the afternoon,

and at six o'clock Latham was first to take off, soon

followed by Sommer pilots Georges Legagneux and

Lindpaintner. When they had proved that flights were

possible several more flyers came out. Cheuret and

Nicolas Kinet took off in close succession in their

Farmans and flew closely above Olieslagers, but a

collision was avoided. Weymann, Ferdinand de Baeder and

Martinet also took off, all flying at minimum altitude

except Latham, who as usual wasn't afraid of heights.

De Baeder suddenly turned inside the course and returned

in front of the grandstands in the opposite direction,

predictably to be punished with a fine for his irregular

flying. Efimoff and Fischer took off, while Olieslagers

joined Latham at 150 metres, before the latter swooped

down and made a tight turn. Weymann suffered some bad

oscillations in the turbulent air. Wagner took off,

followed at 18:40 by André Frey on Émile Bruneau de

Laborie's big Savary biplane. Frey only got to the

end of the first straight before he had engine troubles

and made a heavy landing in an unmown alfalfa field. The

plane was wrecked, but the pilot escaped without injury.

Daillens was hit by a gust and broke the landing gear of

his machine when he touched down.

Labouchère, Bartolomeo Cattaneo (Blériot), and Hanriot

took off, making it fourteen machines in the air at the

same time. There was some light rain and like on the

first evening the spectacle was improved by a beautiful

rainbow. Christiaens, de Mumm, Morane, Émile Aubrun

(Blériot) and Thomas joined "la ronde

infernale", the "infernal circle", making

it eighteen machines in the air! Ladougne also took off,

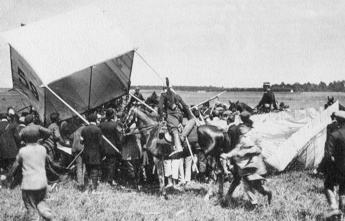

and then chaos broke out as five machines came down

almost simultaneously at the far end of the airfield.

Ambulance services, reporters and officials, headed by

the responsible commissioner M. Houdaille, rushed away on

horseback, in automobiles or on foot. From the press

pavilion little could be seen even with the help of

binoculars, and rumours started to fly before the

officials could return with some facts. Thomas and

Weymann had made emergency landings without major dramas.

Cheuret had come down in an unmown oat field, breaking

the right wings of his Farman. Léon Bathiat had put his

Breguet vertically on its nose after an emergency landing

that ended in a pirouette-like ground loop, only metres

away from Cheuret. Martinet's engine had failed and

in the following crash he was thrown some ten metres from

his machine into the wheat. The sight of a pilot carried

on a stretcher on the opposite side of the airfield

raised grave concerns in the grandstands in view of the

fatal accident of the previous day. After a while it

emerged that the pilot was Martinet, and that his

injuries thankfully weren't life-threatening, only

two broken ribs. The other three pilots were

unharmed.

Then the cannon was fired, announcing that it was half

past seven and that the day's official flying was

over. Flights had only been possible during two hours,

but there had been an enormous lot of action and all in

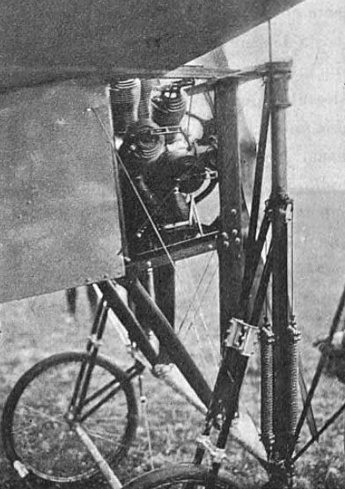

all 29 pilots had flown. Morane, in his new 100 hp

14-cylinder Blériot, had won the daily speed contest by a

broad margin. He was the first to break a world record

during the meeting by covering the ten kilometres in

6:48.0, corresponding to 88.2 km/h. There would be many,

many more records broken in the following days… Latham

had made the day's longest flight. His 105 kilometres

beat Olieslagers' 85, and that single flight was also

good enough to win him the prize for the day's

longest aggregated distance. Olieslagers tied the 105

kilometres, but his flights had taken longer time.

After the official flights had ended a couple of

passenger flights were made, Aubrun with fellow Blériot

pilot Julien Mamet on board and Morane with Jorge Chávez

on board, the former perhaps giving new Blériot customer

Chávez instructions on how the machine worked. Bouvier

made a final test flight.

During the first two days of the meeting the unmown

fields outside the course had claimed five machines

during emergency landings. The 1909 meeting had been held

later in the year, when most of the surrounding fields

had been harvested, but now only a strip of around 100

metres had been cleared. The organizers hid behind the

rule that it was forbidden to land outside the course,

but, as pointed out by somebody, "rules are made on

the ground and not valid in the air". Another risk

that was pointed out was the kite trains that were

launched inside the course. They reached an altitude of a

couple of hundred metres and the consequences of an

airplane flying into their mooring wires would of course

have had been catastrophic.

Tuesday 5 July

During the morning the funeral services of Charles

Wachter were held in Reims, at the house of the Krug

family, friends of the unfortunate pilot. A large number

of officials, pilots, reporters and Antoinette employees

were present. His coffin was then taken to the railway

station for transport to Puteaux outside Paris, the

hometown of Léon Levavasseur, where he would be

buried.

Already at seven o'clock in the morning Jacques

Balsan made a successful test flight, showing good speed.

Édouard Nieuport also made a test in the morning in his

little monoplane, but otherwise there wasn't much

activity. When the official flights started at eleven

o'clock the weather was still good, with only light

winds. The main events of the day were the qualifications

for the speed contest and the qualifications for the

French team for the Gordon Bennett Trophy race, which was

to be held at Belmont Park in New York in October.

The qualifications for the speed event started

immediately. Three machines at a time were flagged off to

fly 20 kilometres, each with a delay of a minute, with

the best of each heat advancing to the next round. The

first starts went well and Wagner, Weymann, Nieuport and

Louis Blériot's partner and pilot Alfred Leblanc

completed their flights, while Ladougne and Alexander de

Petrovsky (Sommer) failed to complete the distance. After

only twenty minutes, just as Latham prepared to start,

the weather turned worse, with thunder and heavy rain,

followed by mist and a fine rain. At noon Jacques Faure,

with Marquis de Polignac as passenger, took off in a

balloon from Place du Boulingrin in central Reims, but

the wind refused to take it over the airfield and it

disappeared from sight in minutes.

At two o'clock the weather had improved again, but

nobody except the kite-flying officers ventured out onto

the waterlogged field until seven minutes past three,

when Mamet took off and climbed to 60 metres.

Lindpaintner followed him. At a quarter past three Latham

took off, and soon passed above Mamet, whose machine was

upset by the turbulence and had to land.

Due to the rain the time for the speed contest was

delayed by three hours, which meant that the two contests

were run at the same time, while other competitors were

circling the field adding laps to their tally for the

total flight time prizes. This made it very difficult to

keep track of what was going on, and the visitors in the

grandstands must have been completely confused. Even the

most diligent reporters, like Frantz Reichel of "Le

Figaro" and Pierre Souvestre and André Guymon from

"L'Auto" gave up trying to report in

detail. Realizing that one signal mast would be

insufficient, the organizers had installed two masts on

the airfield, but they couldn't by far report on all

the machines that were in the air at the same time. All

results were reported on the enormous result board behind

the grandstands, which had one column for each contestant

and one line for each event, but this could of course not

happen immediately. The proceedings were

"incomprehensible to the public and only barely

comprehensible for the initiated", according to

Souvestre, and the circulars containing the final results

of the day were not published until half past eleven in

the evening.

Leblanc completed the 100-kilometre distance for the

Gordon Bennett qualifications in 1 h 19:13.6, having to

run an extra lap in order to compensate for missing a

pylon in the hard wind. After the landing he seemed to

lose control of the plane, which like other airplanes of

that era did not have any brakes. It swerved towards the

fence in front of the grandstands. The dangerous

situation was saved by the pilot, who acrobatically

jumped out of the machine, which was rolling on the

ground, and managed to get hold of the left wing to stop

it. Behind him Latham took the second place, his time 1 h

24:58.6. Later, at six o'clock, Ladougne made his

effort, showing good speed in the fastest of the biplanes

but failing to complete the 100 kilometres. Labouchère

was in the air at the same time, taking the third place

with 1 h 25:24.0, the three monoplanes being the only

ones to complete the distance. According to some reports

Legagneux, de Baeder, Wagner and Mamet also tried, but

failed to complete the distance.

Morane and Leblanc were in a class of their own in the

speed contest, their best times over the 20 kilometres

(13:08 and 13:14, respectively) being more than a minute

and a half better than those of Antoinette pilots Latham

and Labouchère, who posted the third and fourth best

times of the twelve who qualified for the second round.

We have not managed to find a report on exactly how the

heats were composed and how the qualifications worked,

but it appears that at least fifteen pilots took part.

Apart from those mentioned above, it is known that

Olieslagers, de Baeder, Aubrun and Kinet also took

part.

Perhaps because so many pilots had participated in the

day's previous events, or perhaps because the field

was still so wet, there was not so much activity during

the last hour. De Mumm crashed his Antoinette at some

point during the evening. Labouchère, Latham, Wagner,

Olieslagers, Cattaneo and Weymann were all circulating

when the daily altitude contest started at five minutes

before seven. Morane, Olieslagers and Aubrun climbed

high, followed by the slower Latham. Morane won by

reaching 550 metres, beating Latham's 390.

While Morane glided down in a dramatically steep

"vol plané" Latham left the airfield and flew

two circles around the cathedral of Reims at an estimated

altitude of 800 metres before returning to make a perfect

landing. The daily non-stop distance contest was won by

Labouchère, whose 110 kilometres beat the 105 kilometres

of Latham and Olieslagers. The daily total distance

contest was won by Weymann, who covered 135 kilometres,

in front of Latham and Labouchère. During the day's

contests all speed records for all distances up to 100

kilometres were beaten, those from 5 to 20 km by Morane,

those for 30 and 40 km by Olieslagers and the remaining

distances by Leblanc. According to Frantz Reichel of

"Le Figaro" at least 28 pilots had flown during

the day.

Wednesday 6 July

During the first three days of the meeting the weather

had at least been good at times. Not so on the fourth day

- the weather was miserable from early in the morning

until late in the evening. It rained constantly, and the

wind was as strong as on any of the previous days. The

airfield turned into a sea of mud where it was difficult

to drive cars and even horse carts got stuck, so it was

perhaps just as well that nobody wanted to fly. Workers

tried to improve conditions by spreading sand and clinker

on the roads and laying planks in front of the

grandstands.

At a quarter past nine there was suddenly a large cloud

of smoke from the hangar of René Thomas. A mechanic had

been doing some soldering too close to an open fuel

canister. The fuel had caught fire and the flames

threatened the 1,200 metres of wooden buildings that

surrounded the airfield. Thankfully there were lots of

people in the neighbouring hangars and 22 fire

extinguishers were soon emptied over the fire, quickly

putting the flames out. The fire in itself caused little

damage, but one of Thomas' mechanics was lightly

burned and a carpenter who was working in a hangar was

run down and trampled by the horse of one of the soldiers

who galloped to the hangars to help. He was brought to

the airfield hospital to be treated for a fractured

pelvis. Nothing else happened. At eleven o'clock a

team of mechanics brought back the remains of de

Mumm's crashed machine. The officers brought out

their kites, but it was too windy for them too and Basset

suffered from seasickness in his bobbing and weaving

basket. The cannon signalled the start of the day's

official flights at 11:30, but nobody cared. The rain

stopped towards the end of the afternoon and there was

even some sun, but the gale continued to blow and the

rain soon returned.

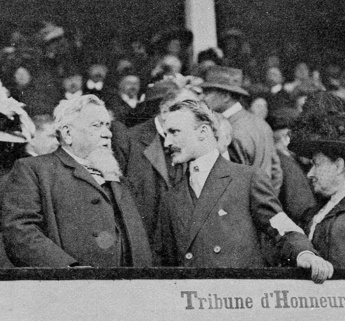

This was the day when Armand Fallières, the president of

France, visited the airfield, and just like the year

before he brought bad weather. He arrived at the airfield

at five o'clock, having taken the train from Paris

two hours earlier. He was accompanied by his wife and son

and a large entourage of ministers, officers and

government personnel. He was greeted by the organization

committee and by the 137th infantry regiment and its

band, before being brought to a meeting with Hermes da

Fonseca, who had been elected president of Brazil and was

on a tour of Europe before officially taking his

position. This was followed by a tour of the hangars. The

president was going to return to his train at half past

seven, and at 19:25, when all speeches had been held and

the preparations for his departure had already started,

it looked like he would have to return to the capital

without seeing any flying. The wind speed reached 13-15

m/s in the gusts.

But, just as the year before, a couple of brave pilots

saved the day. The first machine to be hauled out onto

the mud was Latham's Antoinette, and in the

president's pavilion people got out of their chairs

to watch the action. The president and his wife were a

bit alarmed, since they didn't want anybody to risk

their life for their sake. Latham's machine was

followed by two biplanes, the Farmans of de Baeder and

Weymann. De Baeder was first in the air but landed

already after 250 metres. Weymann was next, his machine

pitching and rolling dramatically in the turbulence

during a one-lap flight. Latham was last to take off and

as usual handled the wind with confident ease during two

laps. All three landed safely in front of the

grandstands, Latham last. Madame Fallières cried

"I'm so pleased, there was no accident!"

and everybody cheered, sighed of relief and got on with

the ceremonies around the departure. The president and

and his entourage were driven to the station and were

back in Paris at ten o'clock in the evening.

Thursday 7 July

The weather was a little bit warmer, but it was still

gusty and rained from time to time. The official flights

started with the main event of the day, the second round

of the heats for the speed contest. The object was to

qualify nine machines for the semi-finals and finals,

which were to be held on the last day of the meeting. The

twelve pilots who had qualified after the first round ran

two by two in six four-lap heats, with the intention to

eliminate the three slowest. In the first heat, Efimoff

failed to take the start on time, while Morane was

disqualified, despite flying an extra lap, after missing

the third pylon on three of his laps. The second heat was

the only one where both planes completed the distance,

with Latham beating Lindpaintner. In the third heat

Leblanc scored the best time, 14:12.2, while Aubrun had

an incident during the take-off and damaged his

propeller. The fourth heat was won by Labouchère, while

de Baeder landed after the first lap. The fifth heat saw

Olieslagers win, while Wagner landed after one lap. The

sixth heat was again a complete failure, when Weymann

failed to start on time and Nieuport landed already after

one lap. After these heats only five pilots had

qualified, so in order to complete the field it was

decided to run three second chance "repêchage"

heats later in the afternoon.

At one o'clock the wind was around 7-9 m/s, so while

conditions were reasonable it was still a bit windy. The

course was left open for the "carousel", the

free session for the pilots who circled the course

competing for the distance prizes. The "desperate

monotony" of this was by now regarded as an ordeal

by some of the reporters, but they could still look

forward to the struggle between particularly Latham,

Olieslagers and Labouchère for new world distance and

endurance records.

The slightly faster Olieslagers was separated from

Latham, who started a little later, by only one minute

and twenty seconds after 150 kilometres. Olieslagers went

on to set a new world record for 200 kilometres, which he

covered in 2 h 47:04.6, and after three hours he had

covered 212.750 kilometres. The 200-km record was soon

erased by Latham, whose time was 2 h 46:02.0. Latham

landed after 215 kilometres, but Olieslagers kept on

flying and at 16:23 the time-keepers signalled that he

had beaten the world distance record, previously held by

Henry Farman at 234.212 km. This coincided with the start

of a rain shower, and Olieslagers landed after 235

kilometres, which he had covered in 3 h 02:04.8.

Labouchère also intended to go for the long-distance

record but had to land after 190 kilometres when he ran

out of fuel. He made a cross-wind landing and

ground-looped his machine, which turned over on its back

at low speed with amazingly small damages.

While this went on, Weymann crashed in a wheat field

after a flight of 25 kilometres. He was unharmed, and he

was back in the air later during the afternoon, flying

another Farman machine. Lindpaintner was driven towards

the fence in front of the grandstands and had to crash

deliberately to avoid hitting them. De Petrovsky was also

in trouble, being forced to the ground by the turbulence

and breaking a wing. He blamed Kinet, who he claimed to

have passed him only 15 metres away, and said that he

intended to file a formal protest. Wagner and Hanriot

impressed with their speed, while several other pilots

tried their wings, among them Bathiat, Ladougne,

Legagneux, Cattaneo, Efimoff, Fischer, Van den Born,

Mamet, Thomas, de Baeder, André Frey, Alfred de Pischof

and Kinet.

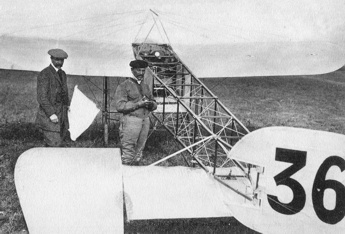

Two of the four announced Army pilots had finally

arrived, their flight from Mourmelon having been

postponed because of the bad weather, and Lieutenant

Albert Féquant in his Farman scored 15 kilometres for the

contest for the officers' prize. Lieutenant Félix

Camerman, whose machine was still at Mourmelon, flew the

machine of Christiaens, and therefore his result

didn't count.

The second-chance heats for the speed contest were run at

five o'clock. Morane was the only starter in the

first heat, his time of 13:46.0 beating the best times of

all the other qualifiers. Wagner won the second heat and

the slower de Baeder dropped out after two laps. It

appears that the third heat, which should have matched

Aubrun against Nieuport, was not run. There were thus

only seven pilots qualified for the semi-finals.

The daily altitude contest ran until seven o'clock.

During the take-off run one of Olieslagers' wheels

got stuck in a rut and the aircraft nosed over and turned

over on its back. The accident was not as bad as it

looked, the Belgian was unharmed and the only damage to

the machine was a broken wheel and a broken propeller.

Latham took off, followed by Balsan and de Baeder, but

the match for the prize was between Latham and Morane,

who disappeared quickly into the sky in his faster

Blériot. Latham disappeared into a cloud and reappeared.

Morane gave up after ten minutes, later stating that he

didn't like flying into the clouds and was frightened

when he didn't see anything. He returned to land in a

steep glide. De Baeder also descended, announcing his

approach by means of a siren and landing smartly

immediately in front of his hangar. Latham kept flying

for another five minutes, flying into and out of the

clouds. Exactly when the cannon announced the end of the

days flying he appeared from a cloud to the right of the

grandstands and started a masterful glide of four or five

minutes, including two circles around the timing tower.

He had reached 1,384 metres, beating Morane's 1,110.

Reports claimed it was a world record, and it still

stands as such in some lists, but it did not beat the

1,403 metres reached by Walter Brookins in a Wright at

Indianapolis on June 17th. Nevertheless, Latham was

hailed as a "surhomme", a superman, and carried

in triumph from the hangars. Around 30 pilots flew during

the fourth day. Olieslagers' total of 255 kilometres

won him the daily total distance prize, in front of

Latham's 230.

Friday 8 July

On the sixth day of the meeting the weather was finally

good, with higher temperatures and almost calm air. The

day saw an unprecedented amount of flying, but this was

overshadowed by the horrific accident of

"Baronesse" de Laroche.

There were already around ten machines in the air, among

them Latham, Lindpaintner, Bunau-Varilla and Weymann,

when she took off at around ten to one. She completed a

lap and then climbed to 50 metres before starting the

second. At the end of the second lap she took a wide turn

at the fifth pylon to avoid some faster competitors. Her

machine then suddenly pitched up, then down, and dived

into the ground, completely breaking into pieces.

Ambulances and reporters rushed to the crash site, which

was some 1,500 metres from the grandstands. They found de

Laroche almost buried in the debris, barely conscious and

obviously very badly injured. She was carefully

stretchered to an ambulance and transported to the

airfield hospital. The initial reports were pessimistic,

and some early reports even stated that she was dying. At

half past three the airfield doctors published a

bulletin, stating that she had suffered a complicated

fracture of the right lower leg and fractures of the left

arm, the left thigh and the left index finger. In

addition to that she had dislocated the right hip and got

several minor cuts and bruises. Her injuries would

certainly have been worse if she hadn't tried to rise

off the seat to avoid hitting the control wheel in the

crash. The doctors' forecast stated that there was

hope for her recovery. She was transported to the surgery

of doctor Roussel in Reims, where her fractures were set

during the late evening, without sedation and with only

chloroform for pain relief. The bulletins issued

afterwards by the doctor were carefully optimistic.

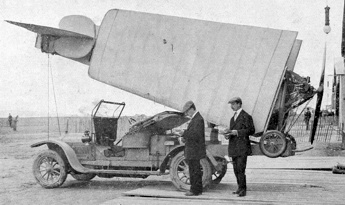

Initial rumours said that the accident was caused by

Lindpaintner passing her too closely and forcing her to

fly into his propeller wash. He was rudely abused and had

to be protected when he returned to the pits. The

officials, represented by sports commissioner Édouard

Surcouf, quickly issued a statement that this was not the

case, and that Lindpaintner had been too far away to have

affected her. There were also witnesses who claimed to

have heard the engine stop before the crash. The Voisin,

like other early pushers, had lifting tail surfaces that

were blown by the propeller slipstream. The effect of the

engine suddenly stopping would have been that the tail

lost lift and the machine pitched up, quickly losing its

forward speed.

The controversies were not silenced the by the official

statement, though, and on the next day three witnesses,

including pilots Chávez and Morane, requested that the

incident would be reinvestigated. They claimed that their

observations had been misrepresented and that

Lindpaintner had indeed cut the corner closely in front

of de Laroche. The "procureur de la republic"

(public prosecutor) of Reims announced that he would open

an enquiry into the conditions around the accident,

according to "Le Figaro" for the first time in

the history of sports.

While everybody was following the rescue and the reports

about the status of the baroness, another accident

happened. This was de Petrovsky, who was now flying the

Sommer of Efimoff, since his own machine was damaged the

day before. He crashed rather heavily and the machine was

badly smashed up, but the pilot escaped with a fractured

wrist.

With these dramatic incidents on everybody's minds it

is natural that the reporting of the day's other

activities suffered, but in many ways it was a repetition

of the day before. Olieslagers and Latham again crossed

horns trying to break the distance records. Latham

started a little earlier and flew the first 100

kilometres in 1 h 20:30.0, not quite matching

Olieslagers' record of the day before. Olieslagers

was not as fast as Latham during the first hour, his time

half a minute slower at 1 h 20:51.6, but then he must

have turned up the wick, because he reached 150

kilometres in 1 h 58:20.4, beating that record of the day

before. Starting first, Latham was first to reach two

hours and posted a new record of 147.750 kilometres. His

joy was short-lived, though, since Olieslagers reached

152.125 kilometres in the same time. Latham landed after

160 kilometres, which he reached in 2 h 09:33.6, while

Olieslagers continued to reach 225 kilometres in 2 h

55:05.4, in the process also beating setting a new

200-kilometre record of 2 h 35:18.2. After the flight he

said that he was disappointed not to have gone further,

but he had run out of fuel. Both Latham and Olieslagers

went up again, the latter lowering the 100-kilometer

record to 1 h 16:42.2 and that of 150 kilometres to 1 h

54:54.4 before landing after another 195 kilometres and 2

h 29:34.4 in the air, having covered a total of 420

kilometres in one day - the distance between Paris and

London! Latham landed already after 40 kilometres.

Meanwhile, the short-distance speed records also fell.

The 10-kilometre record was beaten first by Morane's

6:35.0, and then by Leblanc's 6:33.6. Leblanc also

set a new 5-kilometre record during the same flight,

covering a lap in 3:12.8.

In the shadow of the record-beaters several pilots flew

impressive distances. Cattaneo made a non-stop flight of

170 kilometres, beating Latham to second place in the

daily contest, while Labouchère was fourth at 125 and

Kinet fifth at 110. Legagneux flew a total of 300

kilometres during the day, winning the second prize in

front of Weymann's 270 and Cattaneo's 260. The

Voisin pilots didn't have much to cheer for, but

Bunau-Varilla flew 100 kilometres in 1 h 23 minutes,

which was claimed to be a world record for biplanes.

Altogether 32 pilots flew during the day, 13 of them

covering more than 100 kilometres. The busy time-keepers

had registered no less than 760 laps flown!

After the end of the official flights several of the

pilots, among them Leblanc, Aubrun, Morane, Legagneux and

Bathiat took prominent guests for passenger flights.

Bathiat's passenger probably got more excitement than

he had asked for when the machine crashed, but neither

the pilot nor the passenger was injured.

Saturday 9 July

The weather was calm, with winds of only 3 m/s, but low

clouds covered the airfield. This was the last day of the

constructors' prize, so it could be expected that

many would go for long-distance flights. At the beginning

of the day, Antoinette stood at a total distance of 1,701

kilometres flown by their three best machines, Blériot at

1.463, Farman at 1.427 and Sommer at 1,269. It had been

decided during the morning to deduct the 270 kilometres

that Weymann had flown the day before from Farman's

total. According to the rules it was the machines that

counted, not the pilots, and several competitors had

protested that the machine Weymann used on the Friday was

not a rebuild of the machine that was damaged when he

crashed on the Thursday, but a completely different

machine.

When official flights started at eleven o'clock,

Thomas was first to take off, accompanied during the

following half hour by Daillens, Legagneux, Latham,

Wagner, Fischer, Kinet, Lindpaintner, Labouchère,

Olieslagers, Weymann and Cattaneo. At half past eleven

Mamet took off with two passengers on board, his brother

and his mechanic M. Lemartin. He landed after a flight of

97.750 kilometres, having beaten all two-passenger

records for both speed and distance. Latham landed after

125 kilometres, Fischer after 100 and Weymann after 95.

Lindpaintner, Olieslagers and Legagneux landed after 65

kilometres. Thomas made two flights of 90 kilometres each

but his second landing, around a quarter to four in the

afternoon, was very heavy. It broke the upper rigging of

his machine and made the wing tips drop to the ground.

André Noël also crashed his Blériot when the machine was

hit by turbulence, but apparently without any

injuries.

Labouchère landed after 40 kilometres and after a short

pause took off again at 12:43. Aubrun took off with one

passenger on board and made a flight of 85 kilometres,

also beating several passenger speed records. Olieslagers

was busy too, beating the records for 50 kilometres and

for one hour. Morane took out the 100 horsepower Blériot,

making "a terrifying impression, like an arrow that

splits the air". His time for five kilometres was

2:51.0, corresponding to 105 km/h, a new world record.

Lieutenant Camerman finally flew in from Camp de Châlons,

some thirty kilometres away, on a Farman with the French

"tricolore" flying from a wing strut. This

meant there could finally be a contest between the two

military pilots on the last day of the meeting. When he

was congratulated for his 24-minute cross-country flight,

made at altitudes up to 400 metres, he didn't accept

any praise and modestly replied "J'étais en

service commandé".

While this went on, Labouchère just kept flying and

flying. At 16:26 the signal mast indicated that he had

beaten Olieslagers distance record from two days before,

but he didn't stop. After 4 hours and 14 minutes he

reached 300 kilometres. After 4 hours and 39 minutes he

finally landed, having flown 340 kilometres. When

interviewed in the evening he stated that he had believed

that the extra-large fuel tank would have kept him in the

air for five hours, so he brought bread, chocolate,

cookies and fruit to eat. He had eaten for the first time

after one hour. He said it was impossible to count the

laps, so he had watched the signal mast to keep track of

his progress. He was worried that it didn't show

anything at all in the beginning, not until he had

completed the first 100 kilometres. When he finally saw

the white ball that signified a world record hoisted

beside his signal, a red ball and a red

"diabolo" double cone, he knew that he had

succeeded and celebrated with a second meal of bread and

chocolate. He didn't want to risk running out fuel,

so he decided to land after four and a half hours.

Aubrun made a second passenger flight, reaching 137.135

kilometres in 2 h 09:07.8 with Émile Reymond, a senator

from Loire, on board, beating his previous mark. This new

world record flight did not count for the passenger

prize, however, since he had started after the end of the

time allowed for the contest. As all the reporting of the

day's flying centred on the record-beating, there

were unfortunately few reports of the rest of the

day's flying in the press. As usual, the daily

altitude contest was held at the end of the day. It was

won by Morane, who disappeared in the low clouds and

reached 741 metres before making another spectacular dive

for the airfield, with de Baeder placing second.

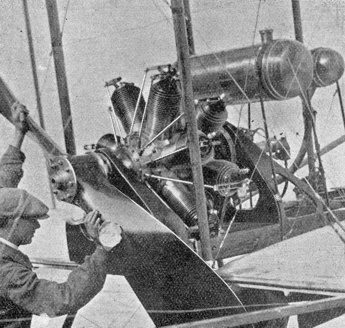

The standings in the "Grand Prix de Champagne"

didn't change during the day. The Antoinette team of

Labouchère, Latham and Thomas won the 50,000 francs by

reaching 2,601 kilometres, beating the best Blériots of

Olieslagers, Cattaneo and Aubrun by almost 300. The

usually troublesome Antoinette engines ran without any

problems, according to some reports because they were

improved versions with carburettors instead of the fuel

injectors that in the past had proved so sensitive to

contaminated fuel. This reliability was in complete

contrast to the ENV engines. These usually dependable

V-8s failed left and right, forcing Voisins, Savarys and

de Mumm's reengined Antoinette to make emergency

landings time after time. The engine of

Bunau-Varilla's Voisin was replaced four times during

the meeting!

The Sommer pilots made several passenger flights and when

the cannon announced the end of the day's flying,

Legagneux was flying above the cathedral of Reims with

Paul Painlevé, the politician, mathematician and creator

of the world's first university course on

aeronautics, on board. Without any previous practice on

the type Chávez made his first flight in a Blériot,

having decided to buy one in place of his Farman. Before

starting, he said "if it stumbles, I will stop, if

it goes well I'll fly right away". He pulled the

stick after a roll of 20 metres, immediately climbed to

200 metres and made a flight of 30 minutes.

Sunday 10 July

The main events of the last day of the meeting was the

semi-finals and finals of the speed contest and the

cross-country race for the "Prix Michel

Éphrussi". The weather was fine, and the wind was

less than 3 m/s. Since six o'clock in the morning

there had been a steady flow of people on foot, on

bicycles and on kinds of cars and carriages heading

towards the airfield. Trains arrived every five minutes

to the temporary station at Fresnois. The grandstands and

public areas were full of people and it was estimated

that more than 100,000 people watched the day's

flying.

The first semi-final of the speed contest staged Morane

against Lindpaintner. The Frenchman won, as expected. His

time was 12:49.6, beating Lindpaintner by the huge margin

of seven minutes over the twenty kilometres. In the

second semi-final, Leblanc won by walkover, since

Labouchère couldn't make the start, but he still

finished the distance in 12:58.8. Three pilots contested

the third and slowest, but most exciting heat, in which

Olieslagers overtook both Latham and Wagner and won the

last of the three places in the finals.

The finals were run at 12:20. Morane was first to get the

starting signal, with Leblanc and Olieslagers following

at one-minute intervals. They finished in the same order,

with Morane scoring the best time over the distance

during the meeting, 12:45.6, yet another new world

record, beating Leblanc by ten seconds and Olieslagers by

thirty.

Many pilots tried to improve their results in the total

distance contest. Fischer flew 175 kilometres in a flight

of 2 h 26:24 and Labouchère flew 100 kilometres. Kinet,

Cattaneo, Bouvier, Weymann, Thomas and Legagneux also

added considerably to their totals. There were a couple

of incidents, too: Latham's Antoinette pitched down

and hit the ground in front of the grandstands. Paul

Hesne made a heavy landing in his Breguet, but without

causing any damage, while Bathiat in the other Breguet

had a third accident when his machine nosed over close to

the timing tower, also this time with only minor damages

to the wings of the sturdily built machine. Lieutenants

Camerman and Féquant contested the officers' prize,

the former flying the 50 kilometres in 46:50, beating his

colleague by 50 seconds.

At three o'clock Olieslagers took off again, with the

intention to take the world distance record back from

Labouchère. His Blériot was now equipped with extra fuel

tanks both above and below the fuselage. At 5:10 it was

announced that he had broken the speed record for two

hours, at 5:15 the record for 200 kilometres and then

followed records for all whole and half hours and for

every even 50 kilometres flown.

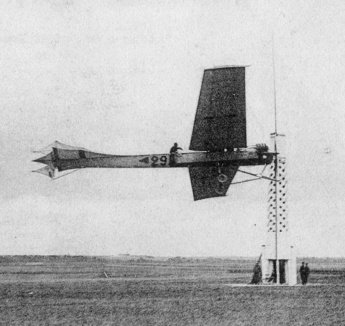

At six o'clock, when Olieslagers had been in the air

for three hours, a cannon shot called the ten competitors

to line up for the Prix Michel Éphrussi, the first air

race ever where planes started side by side, in racehorse

style. Eight were monoplanes, flown by Wagner, Hanriot,

Latham, Morane, Leblanc, Aubrun, Nieuport and de Pischof.

Aubrun was also carrying a passenger, a Madame

Charbonnel. The remaining two were Farman biplanes, flown

by Lindpaintner and Weymann. The course would first take

the flyers eastwards from the airfield to the church

tower of Witry-lès-Reims, which could be seen from the

airfield. The second leg took the flyers out of sight,

northeast towards the next turning point, a factory

chimney in Bazancourt. The third and last leg was a long

straight past the village of Fresne-lès-Reims and back to

the airfield, making a total distance 22.4

kilometres.

The machines were released three by three, by shots from

the starter's pistol. Wagner was first off the ground

in the #66 Hanriot originally entered for Fernand

Delétang, followed by Marcel Hanriot and Lindpaintner.

The second trio consisted of Aubrun, Latham and Morane,

but the latter failed to make the start because of a

blocked fuel line. De Pischof, Nieuport and Leblanc took

off in the third trio, Leblanc making it look like the

others were standing still. Weymann was alone in the

fourth set, in an un-numbered spare Farman, but he

retired to his hangar after only two minutes. Aubrun

failed to take the first turn correctly and had to return

to pass the church tower a second time. Wagner was also

first to return to the airfield, easily recognizable by

his bright red jersey. He only placed second, though,

because Leblanc was close behind and his time of 20:14.0

had Wagner beaten by 43 seconds. Lindpaintner glided into

the airfield from high, probably knowing that he had no

chance against the faster monoplanes, and then Hanriot,

de Pischof and Nieuport arrived almost simultaneously. In

the results Nieuport was a distant third, more than two

minutes slower than Leblanc, but it was still a great

performance by his little monoplane, which only had a 20

horsepower two-cylinder Darracq engine. Latham had to

make an emergency landing in a field three kilometres

from the airfield.

Meanwhile, Olieslagers was still in the air. He had

passed 320 kilometres when the time allowed for the total

distance prize ran out, so the remaining distance would

not count for the official results of the meeting. He

flew on for four and then five hours, beating records all

the way, and finally landed after 5 h 03:05.2, having

flown 392.75 kilometres, a fantastic new world record.

This also meant that he took the lead in the Coupe

Michelin, which was offered for the longest non-stop

flight during the entire year of 1910. One report stated

that Olieslagers followed a strict diet during long

distance flights, only drinking lemon juice and eating

dried meat while flying, while another report claimed

that he brought sandwiches and Flemish beer aboard!

In the altitude contest Chávez climbed to 1,150 metres

after a somewhat uncertain start in only his second

flight in the unfamiliar Blériot. He gave up after

reaching the clouds, in which he didn't feel he could

tell which way the machine was pointing. He beat

Morane's second place result from the Thursday but

failed to reach Latham's 1,384 metres, also set on

the Thursday. De Baeder, Cattaneo, Lindpaintner, Wagner

and Tétard also tried, all beating their previous best

efforts. At seven o'clock, when the meeting closed,

lieutenants Féquant and Camerman took off to fly back to

Camp de Châlons. They were followed by Maurice Colliex,

who flew his Voisin to the company base at Mourmelon, on

the same field as Camp de Châlons. The last flight of the

day was made by Mamet, who took off at half past seven

with journalist M. Poillot on board. They quickly climbed

to 500 metres and flew to Reims. On the way back, they

lost their way in the increasing darkness and landed at

Witry-lès-Reims, some five kilometres east of the

airfield, before they found their way back.

Conclusion

Due to the bad weather the meeting didn't attract as

many spectators as the previous one, but otherwise it was

from all sporting, financial and organizational aspects a

complete success. Nevertheless, an event of that size

wouldn't be organized again until after the Great

War. The Reims meeting had outgrown itself, and the huge

effort and expenses of a follow-up meeting could not not

be justified.

It had been realized already during the biggest meetings

earlier in 1910 that the novelty of simply seeing

airplanes fly soon wore off, and that the uninformed

crowd in the end found the endless circling of airplanes

at safe speeds and low altitudes rather monotonous. The

lack of public announcement systems and other practical

means of informing about what was going on surely played

a part, since only the most initiated could tell whether

the plane just passing by was on a world record flight or

simply cruising. The simple fact was that too much went

on at the airfield at the same time and even the

initiated reporters found it difficult to keep track. The

safety issues of the dense traffic around the course were

also a concern, and several accidents were caused by

airplanes being upset by the turbulence created by

others. A new format of air racing would be tested a

month later, the multi-stage cross-country "Circuit

de l'Est"!

A month after the meeting it was reported that 21 flyers

who had damaged their machines during the meeting were

going to sue the organizers for damages. They claimed

that their machines had been unnecessarily damaged by

landing in the high crops outside the narrow mowed strip

along the course, which did not conform with the

regulations of the Aéro-Club. Martinet, who had been

hospitalized for three weeks, claimed an additional

20,000 francs. It would be interesting to know how this

process ended...

The bulletins regarding the status of de Laroche became

more and more optimistic for every day. She faced a long

rehabilitation, but eventually recovered completely. She

was back at the controls of an airplane in 1912, and

after being grounded during World War One she lost her

life in an accident while testing a Caudron biplane in

1919.

Back to the top of

the page

Back to the top of

the page