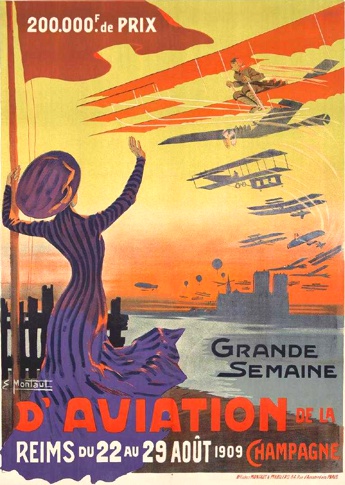

Reims, France, August 22th - 29th 1909

A milestone in aviation history: The first international air race

The 1909 Reims meeting was without comparison the biggest aviation

event of 1909. Almost everybody was there, almost every record was

broken and in many ways it was the event where it was finally proved to

the public that flying was something practically possible, not just

some novelty. A book could be written about the event, but here we will

try to summarize it in just a few web pages.

In 1909 Reims was a wealthy town of around 100,000 inhabitants. It is

the main city of the Champagne wine district, and even though the

vinyards had just gone through the disastrous invasion of the

Phylloxera aphid, a pest which forced the replanting of almost every

vineyard, the business was blooming.

In November 1908 a committee was created for the organisation of the

aviation meeting. It was headed by marquis Melchior de Polignac,

manager of the champagne house Pommery & Greno, and included

representatives from several other champagne houses. They took help not

only from the aviation organizations, but also from the Automobile-Club

de France, which had experience of organizing automobile grands prix.

They guaranteed a minimum of 150,000 francs for prize money and

estimated that it would cost 200,000 to organize the meeting - enormous

sums! Contributions came from several sources, the city of Reims

contributed 40,000 francs and several champagne houses made big

contributions. In February the regulations were finalized and it was

announced that the first heavier-than-air Gordon Bennett Trophy, whose

running had been entrusted to the Aéro-Club de France, would be part of

the program. This is a list of the events:

- Grand Prix de la Champagne et de la Ville de Reims: Longest non-stop flight (100,000 francs, of which 50,000 to the winner)

- Coupe d'Aviation Gordon-Bennett: Highest speed over two laps (25,000 francs plus a trophy worth 12,500 francs to winner)

- Prix de la Vitesse: Highest speed over three 10 km laps (20,000 francs, of which 10,000 to the winner, donated by Heidsieck Monopole and Louis Roederer))

- Prix du Tour de Piste: Highest speed over one lap (10,000 francs, of which 7,000 to the winner, donated by Pommery et Greno)

- Prix des Passagers: Highest speed over 10 km with the highest number of passengers (10,000 francs to the winner, donated by Veuve Cliquot-Ponsardin)

- Prix de l'Altitude: Highest altitude reached (10,000 francs to the winner, donated by Moët et Chandon)

- Prix des Aéronats: Highest speed of a dirigible over five laps (10,000 francs to the winner, donated by G-H Mumm)

- Spot-landing contest for balloons: From central Reims to a point decided by the Aéro-Club (2,000 francs, of which 1,000 to the winner)

The first competitors arrived in the middle of August and started their test flights. On August 16th, six days before the start of the race, a violent thunderstorm struck the field, destroying several of the installations. The roofs of the grandstands and the first line of hangars were quickly repaired, but the second line of hangars had to be more or less completely rebuilt. The biggest damage was done to the one of the airship hangars, which was completely blown down.

The weather had already disturbed the preparations, since the unusually bad weather had delayed the harvest. On many of the fields around the course crops or hay sheaves were still standing and the constant rain turned the airfield into a sea of mud, making it impossible to drive cars. On the day before the start of the race the contest committee held a meeting, even though some members couldn't come due to the poor state of the roads. It was decided to go ahead with the proceedings, even though there would be no efforts to encourage visitors during the first day. There would still be around 50,000 spectators during the first day...

Sunday August 22nd

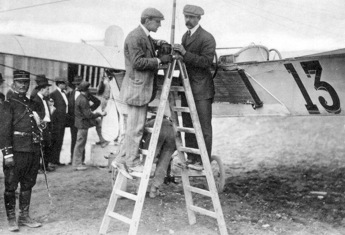

The first event of the meeting was the qualifications for the French Gordon Bennett Trophy race team. This 20 km race was to be held between 10:00 and 15:00 on the first day. The purpose was to select three planes and three substitutes. Twenty planes were entered and the starting order was decided by lots. The wind was quite hard, around 8-9 m/s, around half the top speed of the planes. Latham was first in line, but chose to abstain. Guffroy in the #1 REP then tried, but got stuck in the mud and couldn't get going. Soon before eleven o'clock Tissandier started in the #4 Wright, but he was caught by a gust and had to land again after less than a minute. Blériot took off in the #23 Blériot XII in very strong wind, but had to land after three kilometres because of carburettor problems. Then Latham took off in the #13 Antoinette and passed the starting line, but landed after around 500 metres due to engine problems. "De Rue" took off in the #17 Voisin, but only managed 100 metres before a bad rainshower forced him to shut down his plane, which had veered dangerously in the direction of the grandstands.

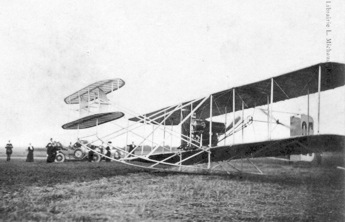

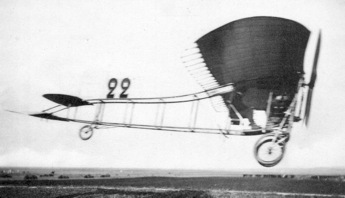

Shortly after noon the weather improved and at 12:20 Eugène Lefebvre took off in the #25 Wright, starting from the Wright starting rail but without using the catapult, since the wind was so strong. He made a flight of more than 29 kilometres in a wind that reached 9 m/s, before he was forced to land because of a broken spark plug. Blériot took off again in his #23 and rounded the first pylon before being forced down, hitting some straw sheaves with the tail and breaking the propeller and stabilizer.

When the time had run out only Lefebvre had covered the required distance. The rules allowed the race committee to decide the members of team in case too few completed the 20 kilometres, and it was decided that Blériot's efforts had also been sufficient to qualify. It was decided to give the remaining places on the team to the pilots who posted the best results during the rest of the day.

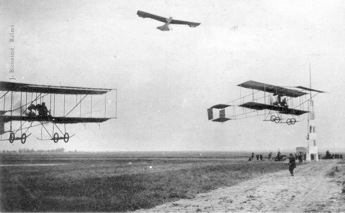

The weather improved and the last hours of the first day saw "the most extraordinary spectacle that has ever been given to the world to see" – six planes flew at the same time, while a rainbow appeared in front of the tribune! A further ten planes flew later – "unique and unforgettable visions, sensations of astonishment, joy, aesthetics and beauty, we could not wish for more!". The reporter from Daily Mail wrote enthusiastically, but perhaps not completely truthfully, that "the sky was black with airplanes"...

Efforts for the one-lap (10 km) Prix du Tour de Piste race were allowed on all days of the meeting. The top three after the first day all flew Wright planes, with Lefebvre leading at 8:52.2, before Tissandier and de Lambert.

Efforts for the three-lap (30 km) Prix de la Vitesse were only allowed on the 22nd, the 24th and the 29th. Five pilots posted times during the first day, with Tissandier fastest at 28:59.2 before de Lambert and Lefebvre. In order to ensure as much flying as possible on all days the rules of Prix de la Vitesse prescribed that participants who didn't post a time on the first two days would get a penalty of five percent on their best time for each of the day he didn't compete. This controversial rule probably kicked back on the organizers, since so many pilots were handicapped in comparison to the few pilots who could post times on the first day. The Wrights had a big advantage during the first day, since they started from a catapult rail and were not hindered by the mud.

Monday August 23rd

In contrast to the first day the conditions were very good, even thought the wind was still disturbing for much of the day. The clear weather made it possible to see the skyline of Reims with its famous cathedral.

The main event of the day was the qualifications for the "Grand Prix de la Champagne", the distance contest. Only pilots that crossed the start-finish line in flight on the Monday would be eligible. This meant that everybody who wanted to take part in the big-money event had to fly on the Monday - and they did, at most six planes at the same time, with varying success. Curtiss claimed that once when flying over the field he saw "as many as twelve machines strewn about the field, some wrecked, some disabled and slowly being hauled back to the hangars by hand or by horses". This might well have been on the chaotic Monday. At the end of the day eighteen planes had qualified.

Towards the end of the day Blériot took his #22 for an effort at the "Prix du Tour de Piste". Nobody else was flying, so he had a clear run. He finished his run in 8:42.4, easily beating Lefebvre's previous mark. Curtiss responded immediately with a time that was seven seconds quicker, 8:35.6. Latham's best time in his #29 was a disappointing 9:13.8.

At the end of the day Lefebvre made his first display of aerobatics, making a series of swoops, dives and steeply banked turns close to the grandstands. His spectacular flying made him a crowd favourite, and he repeated these displays at the end of most days.

Tuesday August 24th

The weather started splendidly, but the wind got stronger during the morning, making all flying impossible. At 14:45 the wind was still 7 m/s, it was getting cloudier, and nobody had made any flights. Nevertheless, the grandstands were filling up and it was impossible to find a table in the restaurants.

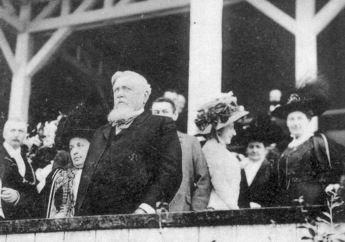

The organization committee had invited the president of France, Armand Fallières. He arrived in a motorcade of eight cars, together with an entourage of ministers, officers and their wives. They were received at around four o'clock by Marquise de Polignac and the organizing committee and were taken on a tour of the installations and hangars, visiting in turn the Latham, REP, Blériot, Delagrange, Gobron, Voisin, Sommer, de Lambert, Tissandier, Lefebvre, Curtiss and Paulhan hangars, where the pilots explained all the features of the various planes and engines. After that Madame Fallières had had enough, so the rest of the hangar tour was cancelled. After less than two hours the president and his entourage was taken to a specially chartered train back to Paris. Just before they left the wind calmed down to 5-7 m/s, enough for some brave flyers to give a brief display for the president. Bunau-Varilla in the #27 Voisin was first to fly, completing a lap in the difficult conditions and waving his cap as he passed the presidential tribune. Blériot also made a short flight. Paulhan in the #20 Voisin made a full lap of the course and finished it by flying several circles close to the grandstands, also saluting the president.

When the president had left the weather improved and Latham in the #29 Antoinette and Paulhan made efforts for the Prix de la Vitesse, but did not improve on the times posted on the first day. Blériot took out the big #22 plane for an effort at the Prix du Tour de Piste. He broke all speed records and took the lead – the time was 8:04.4 and the new world record was 74.319 km/h.

Wednesday August 25th

The weather was once again awful, the worst weather of the week. Torrential rain fell during the morning and the roads and the airfield again turned into a sea of mud. The wind was blowing at up to 13 m/s. This was the first day of the long-distance "Grand Prix de Champagne" contest, but nobody of the 18 qualified pilots took to the air during the morning. They were in the hangars, checking their planes, waiting for the winds to calm down.

In the afternoon the weather improved again and several pilots rolled out their planes. Fournier crashed his #33 Voisin for the second time and withdrew from further flying. The big hero of the day was Paulhan, who beat the world distance and endurance records. He flew 133.676 km in 2 hours, 43 minutes and 24.8 seconds, constantly fighting the weather. The wind rose to 9 m/s in the gusts, around half the top speed of his plane. The Voisin, with its large vertical "curtains" between the wings must have been awful to fly to in the wind, and at one time Paulhan was blown more than 300 meters off course at one of the outer pylons. He missed his turn and had to recircle the pylon. Before the Reims meeting only six pilots (Wilbur Wright, Farman, Paulhan, Latham, Sommer and Tissandier) had made flights longer than one hour. "Delirious" celebrations broke out – the popular Paulhan was carried to the hangars, champagne corks popped and the orchestra played the Marseillaise over and over again.

While all this was going on Farman and his mechanics were busy in their hangars. The day before the meeting they had taken delivery of a Gnôme engine for Farman's #30 plane. This had arrived too late to be installed before Tuesday's qualifications, so the old engine had to be used for that flight, but now they were rushing to remove the water-cooled four-cylinder Vivinus inline engine and replace it with the new seven-cylinder rotary engine. The Gnôme produced the same 50 horsepower, but it was 60 kg lighter, did away with all the cooling hardware and promised to be more reliable. Would they be able to finish the work in time?

Curtiss improved his time for the Tour du Piste to 8:11.6, still not enough to beat Blériot.

Thursday August 26th

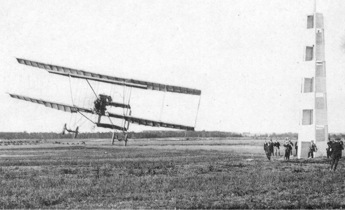

Weather was ideal during the morning, with a light cloud cover and light winds of only 1-2 m/s. Despite this, only a few flights were made until Latham made an effort for the Grand Prix in his #13 Antoinette. In a little over one hour he flew 70 kilometres, beating the speed records for the distances above 30 km, before his engine failed. In addition Latham complained that the plane was badly rigged and difficult to fly. He was not discouraged, though, and started to prepare for a new effort. His fastest lap, 8:32.6, had put him third in the "Tour du Piste" contest.

Curtiss made a couple of flights, testing propellers. He was not pleased with the results and declared that since he didn't have any spares he would save his efforts until the Gordon Bennett race.

At around two o'clock Latham rolled out his #29 plane. This time the wings were perfectly rigged and he had 65 litres of fuel on board, enough for 155 or 160 km. The weather was getting worse again, so he flew at high altitudes, 80-150 metres, in order to avoid turbulence. He didn't fly as fast as during the morning, perhaps because of the weather and perhaps because he was saving the plane. After the fourth lap the wind increased to 8 m/s and got gustier, but Latham didn't seem to be disturbed. He kept on flying, even though it started raining. Eventually the rain stopped and he went on to beat Paulhan's distance record from the day before, covering 154.260 kilometres. Since the Antoinette was much faster than the Voisin the distance was achieved in a shorter time, so Paulhan's endurance record still stood. The flamboyant Latham was also very popular, especially among the female fans, so once again celebrations broke out.

After the end of Latham's flight de Lambert took off for an effort at the Grand Prix. He flew like clockwork for 116 kilometres in two hours his #7 Wright, but then simply ran out of fuel.

While de Lambert was flying two accidents happened, thankfully not resulting in major injury. The relatively inexperienced Rougier in his #28 Voisin turned too late at the last pylon and his direction carried him over towards the spectators that were squeezing against the fences around the field. He had to quickly jump both the fence and the spectators. At this moment the engine suddenly stopped and the plane fell out of the air, on the outside of the fence. A woman who was close to the accident was shocked and fainted and a man was hit by a wheel from the crashed plane. The ambulances quickly arrived, but didn't have much to do.

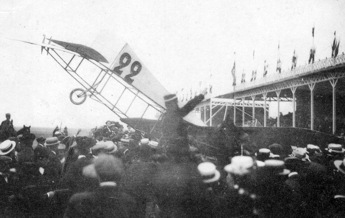

More drama followed. Blériot took his #22 plane up for a flight with Paul Rath, designer of the ENV engine that powered the plane, as passenger. It was perhaps a bit careless to make an unnecessary flight in the team's fastest plane so close to the big races during the weekend, but Blériot wanted to give Rath a ride. He only made a short circuit over the field and then tried to make a hairpin turn at the fourth pylon in order to land as close to the hangars as possible, but his speed was too high and he drifted out over the area in front of the hangars. Seeing that he risked flying over the grandstands he dropped sharply and landed in front of the grandstands, trying to roll out parallel to the fence in front of them and avoid a platoon of soldiers. However, he lost control of the plane, which headed towards the barrier. Men and women scattered in all directions to get away from the fence, which was only breast-high. Some ten meters of the fence was destroyed when the plane hit it at and came to rest on its nose with the tail up in the air. Everybody feared a disaster, but miraculously not a single spectator was hurt. Blériot and Rath were also unhurt, but not the plane. Mechanics had to work through the night in order to repair the broken landing gear and the damaged left wing.

Towards the end of the day Paulhan made a test flight with his #20 Voisin. He was eager to take his distance and endurance records back and had fitted a bigger tank. This enormous "copper barrel" was reported to have a capacity of around 90 litres, allowing him to fly way beyond 200 km. An oil tank of 20 litres capacity was also fitted. Things were shaping up well for the Friday, the last day of the Grand Prix de la Champagne.

The Grand Semaine d'Aviation was not only about airplanes, there was also a landing competition for balloons, organized by the Aéro-Club de France. Twelve balloons took off from Place du Boulingrin in the centre of Reims at three o'clock. Several ladies participated as passengers, notably Mme Surcouf, president of the ladies' aviation society "Stella", and Mme Blériot. A large number of cars followed the balloons and there was great excitement at the airfield when the balloons became visible.

Friday August 27th

The weather was favourable in the morning, light winds and light overcast with sunny spells. The grandstand quickly filled up and many pilots made flights.

At one o'clock Paulhan's hopes of taking his distance record back were crushed. While Paulhan was still only at an altitude of around three meters, Delagrange finished a lap in his Blériot, flying at only 4-5 metres of altitude. Paulhan, still too slow to do much in the way of manoeuvring, was surprised by the appearance of Delagrange in his way, only around 40 meters away. The only way he could avoid a collision was by dropping below Delagrange. He touched down, perhaps a bit violently, and at the same time a gust lifted a wing of the plane, causing the other wing to hit the ground. Perhaps the weight of the increased fuel load was a contributing factor. Anyway, Paulhan's left wings and elevator were destroyed and the propeller was broken in the crash. Although the Voisin team had lots of spares available it was impossible to repair the plane before the evening, so the disappointed pilot had to give up his hopes of winning the 50,000 francs first prize. Thankfully Paulhan was uninjured, except for a cut nose. The distressed Delagrange landed immediately and ran to Paulhan, offering his excuses, but Paulhan refused to put the blame on him – "It's fate", he said. Anyway, Paulhan must be credited for avoiding what would have been the world's first mid-air collision!

At 16:26 Farman took off in his effort for the Grand Prix, still under perfect weather conditions. He had spent most of the week replacing the Vivinus engine of his plane with a Gnôme, actually only putting the engine in place four hours earlier and finishing the installation 40 minutes before the record attempt. The engine had only run on the test stand and he had only made a single short hop before his attack on the world record. The propeller had been finished the day before and transported by train from Paris by his father. Farman's effort was perfectly timed. He knew that he had time to beat the record before the 19:30 curfew, and he was in the air before his competitors. He knew that as long as he kept flying he couldn't lose!

Other pilots also tried during this last afternoon – in all fifteen different planes flew during the Friday. Tissandier in the #4 Wright achieved 111 kilometres, but he had started too late in the afternoon and had no chance of completing a winning distance before the curfew. There was already talk that the Wrights were outdated – were they also careless about their preparations?

Latham also reached 111 kilometres in his #13 plane - but in style! The crowd's hero flew at "breathtaking" altitudes in the Antoinette, the most beautiful airplane, overtaking his slower and lower competitors. Flying at perhaps 100 meters of altitude he simultaneously overtook both Sommer, who flew almost at ground level, and Farman, who flew slightly higher, right in front of the grandstands. The crowd enthusiastically cheered this "spectacle extraordinaire". After flying for more than an hour and a half, another failure of an Antoinette V-8 denied Latham the chance to win the big prize.

At the end of the afternoon Blériot flew four fast laps without beating his best times. Curtiss improved his time over the single lap to 8:09, still not enough to beat Blériot.

While all this went on Farman kept flying, at low altitude, without any dramas. His flying was regular as clockwork, the times hardly differing between the laps. As darkness fell he started to disappear out of sight at the far end of the course. Finally, after a flight of 3h 04:56.4, the 19.30 curfew forced him down. He had covered 180 km and clearly beaten the distance and endurance records of Latham and Paulhan. Still, his victory was not as popular among the spectators – there was nothing heroic about his performance. The conditions were very favourable, so he didn't have to battle against wind or rain like Paulhan or Latham. He had flown the whole distance at low altitude, much of it at less than ten meters. This was not the kind of flying that would enable man to travel between towns, across forests and fields! To the crowd, Paulhan and especially Latham were still the heroes. After finishing Farman landed in front of the grandstands, and celebrations once again broke out - but not as enthusiastic as those of Paulhan and Latham...

Saturday August 28th

Heavy mist covered the airfield during the morning, making it difficult to see the far end of the airfield, but the sun soon made it disappear, and a hot and calm day dawned. Expectations were high before the Gordon Bennett race and people arrived early in order to get the best spots.

The competitors for the Gordon Bennett race only had one effort. They could choose any starting time between 10.00 and 17.00. Test flights were allowed, but the pilots had to declare in advance when their single effort would be made. Countries were allowed three competitors. Apart from the three French representatives who had qualified six days earlier (Lefebvre, Blériot and Latham) there was Curtiss from the USA and Cockburn from Britain in the #32 Farman. Previously announced entries from Austria and Italy had not materialised.

Curtiss figured that the heat would make conditions worse during the day, so he was eager to get his race done as early as possible. He made a test flight in dead calm air at 10.15. This flight broke the record for the Tour du Piste. The new mark to beat was 7:55.4. He decided to make his effort for the race immediately, since he didn't believe that conditions would get better during the day.

At 10.45 Curtiss took off and made his attempt for the Gordon Bennett race. He climbed as high as he could before the start line, so that he could convert the altitude to speed during the first straight. The first lap was completed in 7:57.4 and the second lap in 7:53.2, giving a total time 15:50.6. His flight had not been as steady as usual. The air was already turbulent air due to thermals, and it was speculated that at the high speed the plane had too much lift and had to be held down with the elevator. He finished the race by converting all his altitude to speed on the final straight, as he dropped to less than two meters over the finishing line.

During Curtiss's flight, Blériot took off in the #22 plane for a test lap. His time was 7.58.2, a little bit slower than Curtiss, but very close.

Cockburn was next to try for the full race distance, but he was forced to give up on the back straight on the first lap. On landing he hit a straw sheaf and according to some sources crashed to the ground, being thrown off the plane.

At 11.30 Lefebvre in the #25 Wright made his effort, after having changed to his best engine. At 20:47.4 it was no threat to Curtiss, but still a good, safe flight.

After noon the wind increased to 3-5 m/s. At 12.40 Blériot made a try for the Tour du Piste. His time was 7:59.4, a bit slower than Curtiss' morning time, and he returned to the hangar for checking his engine one more time. At 14.00, Blériot made a second attempt for the Tour du Piste, but again no improvement, only 8:14.2. The crowd was getting anxious and Blériot once again returned to the hangars to work on his engine. At 14.30 Blériot made another test flight, but landed after only one kilometre.

Shortly before 17:00 Latham made his try for the Gordon Bennett Trophy, but his #13 Antoinette was simply not fast enough. He also had bad problems with the turbulence on the back straight. His time was 17:53.0.

Now Blériot was the only hope left for France. As a last resort he had removed the fabric of the 20 cm aft of the rear wing spars of his #22 plane in an effort to reduce the wing area and thereby the lift – a very questionable modification! Blériot's first lap was 7.53.2, equal to Curtiss's best. However, the second lap was slower, 8.03.0, making a final time of 15.56.2, meaning that he lost the race by less than 6 seconds. Blériot had lost the time on the back straight. He blamed an engine misfire, but other sources claim he had to lift off due to turbulence. The crowd was disappointed. The defeat was blamed on nonchalance and bad preparations. Curtiss, in his usual cool manner, briefly celebrated his victory together with the US ambassador in his box in the grandstands, from which the Stars and Stripes was flown, but soon returned to the hangars to rest with some friends.

In the calm evening air Blériot got a small revenge, as he once again took his plane up for a lap for the Tour du Piste. This flight went perfectly, and the time was 7:47.8, beating Curtiss' best time by seven and a half seconds. This corresponded to a new world speed record of 76.955 km/h (47.828 mph), which would officially stand unbeaten for almost a year.

The Saturday was also the day for the Prix des Passagers. The winner would be the pilot who made the fastest lap with the highest number of passengers. Farman was the first to try. His passenger was Frank Hewartson from the Daily Mail, and he flew a lap with ease in 9:52.2. After him Lefebvre flew a lap with Frantz Reichel of Le Figaro as passenger. His lap was slower, 11:05.8. Finally Farman flew a lap with two passengers, Hewartson and a photographer by the name of Letondal. The time for his lap with two passengers was 10:39, faster than Lefebvre managed with only one. Latham tried to make a lap with a M. de Soriono as passenger, but he made a bad start and caused minor damage to a wing. Sommer intended to fly with the English aeronaut and author Gertrude Bacon in his Farman, but on a test flight immediately before he broke a wheel axle, so nothing came of that.

Sunday August 29th

The last day of the meeting was another hot, sunny day. The crowds were bigger than ever before – this was the biggest spectator event of any kind ever in France! The organizing committee announced that they would award a special prize, the Prix des Mechaniciens, for encouraging the hard-working mechanics that had kept the planes flying during the week. A sum of five francs per kilometre flown would be awarded to the mechanics of any plane that flew between 15.00 and 17.00 in the afternoon of the last day. Stops, for example for fuelling or repairs, would be allowed. In addition, prizes of 2000 francs, 1000 francs and 500 francs would be awarded to the pilots who flew the longest distance.

At 10.22 Blériot took off in #22 for an effort at the Prix de la Vitesse. He made a good start, but at the second turn, at the far end of the field where his plane was only visible from the grandstands as a dot on the sky, the plane suddenly caught fire at an estimated altitude of 30 meters and crashed to the ground. Blériot, with his clothes on fire, was thrown out and rolled over the ground to put out the flames. Thankfully the only injuries were a bruised shoulder and minor burns on a hand, and he could get back on his feet without help. He could only watch as the fuel from the broken tank made his plane burn to cinders, while a long black plume of smoke told the spectators what had happened.

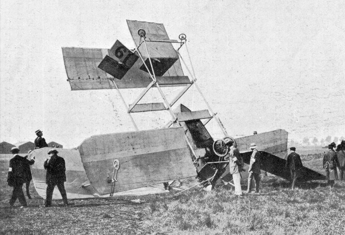

Soon after Blériot's accident Bréguet took off in his awkward-looking #19 plane. He reached an altitude of around four meters and had flown several hundred meters when he lost altitude during a turn and apparently lost control, still at full speed. The plane crashed violently onto its nose, remaining standing vertical after the accident. Bréguet was thrown out of the plane and was quickly brought to the medical services, but he fortunately escaped with only light cuts and bruises.

Around noon the "Colonel-Renard" made its run for the Prix des Aéronats. The fifty kilometres were covered in 1h 19:45, an average speed of more than 37 km/h. At 15.00 the "Zodiac III" took off for its effort. At 1h 25 the smaller airship could not match the bigger "Colonel-Renard".

Bunau-Varilla and Lefebvre made efforts for the Prix de la Vitesse, but did not threaten Tissandier, who still led – but not for long. Latham made two efforts, first with the big #29 Antoinette, then with the smaller #13. The first flight was good enough to take the lead. Latham covered the three laps in 25:18, which including his 5 % penalty was recorded as 26:33.2. The second flight was not as good, at 29:11. Then it was Curtiss's turn. Since he hadn't taken part in any of the previous two days of the Prix de la Vitesse he would get the double penalty (10 %). Nevertheless, he won with ease. His first effort was 24:15.2, but he still wasn't pleased, so he made a second. This time the result was 23:29, which including the penalty was recorded as 25:49. De Lambert also made a try, without improving his time from the first day.

The field was full of planes that were competing for the Prix des Mechaniciens – first two, then three, then finally six planes at the same time. Particularly Bunau-Varilla's and Rougier's efforts were appreciated by the crowd, since they were flying at the sportsmanlike altitude of twenty meters and more, rather than crawling along the ground at three or four metres. The three pilot's prizes went to Bunau-Varilla (70 km), Rougier (60 km) and Sommer (40 km).

At 18.00 the Prix de l'Altitude started. A small balloon was anchored fifty meters above the ground and the competitors would have to fly above it in order for their altitude to be estimated. To the general surprise it was Farman who was first to make his effort – Farman, who had been criticised for his low flying during the Grand Prix de la Champagne! He reached 100 metres to take the lead. Rougier in the #28 Voisin was next, barely clearing the balloon at 55 m. Paulhan's result in his repaired plane was 90 m, not enough to beat Farman. The crowd was already cheering as their hero, Latham, made his effort. He made several circles, partly outside the field towards the south, climbing higher and higher in his beautiful #29 Antoinette, before making his pass between the two pylons that marked the measuring point above the balloon. He came from behind the grandstands, passed over them and high above the balloon. The signal mast announced that the record had been beaten. The result was the "perilously high" 155 metres, another new world record!

This was the end of the week! Altogether 120 official flights had been made during the meeting – only a small number of them have been described above. The total distance flown was 2,462 kilometres, equal to the distance between Paris and Moscow. Latham had flown the longest distance, 569 km. On the Monday most of the planes and pilots were already leaving for other engagements. On the Tuesday the demolition of the temporary installations started.

Why did Curtiss and Farman win?

The big winners, Curtiss and Farman, were both experienced racers, on bicycles, motorcycles and cars. They were focussed on their events, they knew how to compete and win and they used that experience in beating Blériot and Latham. It also helped that the planes of Curtiss and Farman were relatively easy to fly and performed flawlessly. The power loading (hp/kg) of the Curtiss was the highest of the planes at the meeting.

The Blériot XII was quite probably the fastest plane in a straight line, but it had a very high wing loading for its time and was sluggish on the controls. Only three examples were built, and only one sold – which Blériot then refused to repair after a testing accident, offering two Bleriot XIs as compensation! Blériot was a busy man, always tinkering with his planes, talking to media and having meetings, and he made several unnecessary flights that finally resulted in a crash.

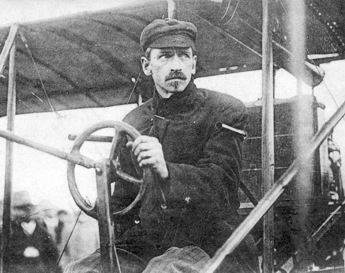

The Antoinette was a very difficult plane to fly, due to its strange controls with elevators and ailerons controlled by two large wheels at the sides of the cockpit. The wings had very sharp leading edges and had very bad stall characteristics. In gusty conditions an Antoinette could actually stall a wing while taxiing, which immediately made the stalled wing tip touch the ground. Furthermore, the Antoinettes had a very flexible structure and relied heavily on correct rigging. As a consequence, Latham had several take-off and landing incidents that required minor repairs. He also had problems with the temperamental Antoinette engines. These very light and rather advanced steam-cooled engines had direct fuel-injection via nozzles in the inlet manifold, which easily got clogged.