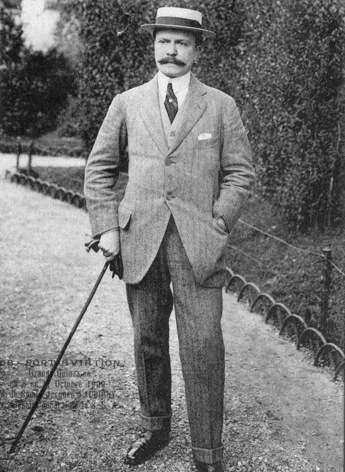

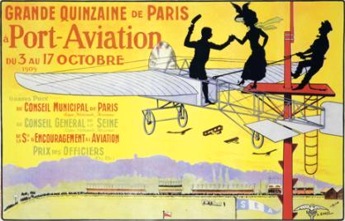

Port-Aviation (Juvisy), France, October 7th - 20th, 1909

During the summer of 1909 it was becoming obvious that the August

Reims meeting would become the biggest aviation event ever. Seeing

this, the Paris-based organisations Ligue Nationale Aérienne (LNA) and

Société d'Encouragement à l'Aviation (SEA) wanted to give the

Parisians something similar. Paris was after all at the time the

world's third largest town and the centre of the emerging French

aviation industry. In the middle of August it was announced that the

event, labelled as the "Grande Quinzaine d'Aviation"

would be held over a fortnight ("quinzaine" in French) from

October 3rd to 17th. The responsibility of the meeting would be split

between three organisations, with the LNA being responsible for the

first eight days, the SCA for the next six days and the Aéro-Club de

France for the fifteenth day. This led to a long and confusing list of

events and prizes, some of which ran only on a single day while others

could be competed for during several days. The race program contained

18 different competitive events, but all of them are not mentioned in

reports. On the other hand, reports from the race mention prizes that

weren't in the race program.

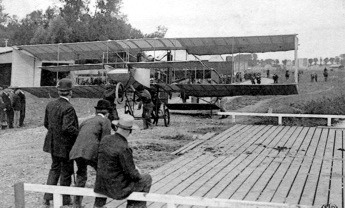

Since there were no suitable sites in Paris itself it was decided to

hold the meeting at the Port-Aviation airfield, which was situated

between the communes of Juvisy, Savigny-sur-Orge and Viry-Chatillons,

around 20 km south of the centre of the town. This field, the

world's first purpose-built airfield, was operated by the SCA and

had hosted the world's first air races in April and May 1909. The

airfield had several marked courses of different lengths. From the

results it appears that courses of 2 km, 1.667 km and 1.5 km were used

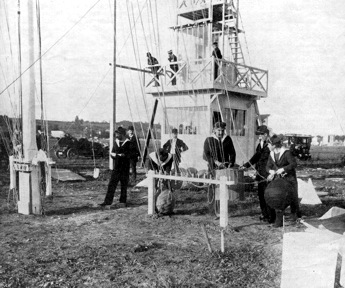

during the meeting. Before the meeting the facilities were expanded

with several new hangars, a signal mast modelled on the Reims one,

enlarged grandstands and automobile parking areas, restaurants, post

office, telegraph and many other spectator services. In addition to the

grandstands a lot of chairs were brought in, bringing the total number

of seats to 30,000. The railway company Compagnie d'Orléans

optimistically promised special train services every four minutes to

the Savigny-sur-Orge station. Several individuals and organisations

offered prizes, resulting in an announced prize sum of 200,000 francs.

Law and order would be ensured by 110 gendarmes on horse-back, several

squadrons of the 27th dragoon regiment and two battalions of the 31st

infantry regiment.

The event quickly gathered a large number of entrants. The list of 43

entrants was bigger than that of the Reims meeting, but it included

several novices, optimists and wannabes from the Port-Aviation flying

schools and hangars. Some were blank entries from manufacturers,

without confirmed pilots. Due to collisions with the meetings in

Frankfurt, Doncaster and Blackpool several of the most famous flyers,

such as Blériot, Rougier and Sommer, were busy elsewhere and didn't

enter. Others, such as Paulhan and Latham, only participated during

part of the meeting, while for example Delagrange and Leblanc did

enter, but never turned up.

Thursday October 7th

The extensive development work on the airfield couldn't be finished

in time, so the meeting had to be postponed by four days. The delay had

the consequence that the split between the responsible organizations

became even more confusing, but had the advantage that it gave the

flyers who had been participating in other meetings more time to

prepare.

The weather was fine on the first day of the meeting, but the patient

spectators had to wait until four o'clock in the afternoon before

they got to see any flying apart from short straight test hops by des

Vallières and Gaudart in their Voisins, Busson in the WLD and the

non-entered Richet (or Richer or Richez, the spelling is different in

different reports...), a pupil of Ferdinand Ferber and his successor as

head of the LNA's flying school, in one of the LNA's Voisins.

Then, at the same time, de Lambert and Gobron made some competitive

flights, de Lambert pitching and rolling in his Wright as it flew low

and caught the gusts between the buildings while Gobron flew higher and

steadier in his Voisin. De Lambert made the longest flight, eight laps

of the 2 km course, during which he posted a time of 11 minutes for the

10 km Prix du Conseil Général de la Seine, which would be contested

during four days. Gobron won the Prix Madame Paul Quinton by flying 2

km in 2:07.6, each lap passing over a balloon anchored at a height of

15 metres, with de Lambert second at 2:10.0.

Friday October 8th

A miserable day with wind and rain, so no flying was possible.

Saturday October 9th

The weather had improved on the next day, but because of the sodden

ground there was no flying until the afternoon. De Nabat, Gaudart and

des Vallières made attempts for the Prix de Lancement, given to the

pilot to take off in the shortest distance from a standing start and

fly a kilometre before landing, but none of them managed to complete

the required distance. De Lambert made the crowds cheer up with a

flight of four laps, followed by a double figure-eight in front of the

grandstands and another two laps. Before the closing of the day, Richet

flew three laps and Gaudart made another short test flight. The flights

made during the day of course counted for the prize for the highest

total distance flown during the meeting, but apart from that there was

no competitive flying.

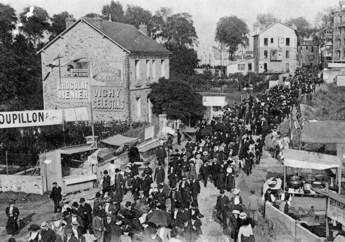

Sunday October 10th

Sundays were the only holidays for the working French, so this was the

first chance for many people to go to the races and for the first time

in their life see aeroplanes flying. It was also announced that the

popular Latham and Paulhan would probably arrive during the day. It was

estimated that around 300,000 people tried to get to get to

Port-Aviation on that day. All forms of transportation broke down. The

roads were completely jammed with automobiles, bicycles and people. The

train service on the Paris-Orléans line collapsed into complete chaos

under the pressure of an estimated 100,000 passengers. The reporter of

"The Aero" stated that it took him more than three hours to

travel the 20 km from central Paris to Port-Aviation in the morning and

four hours to get home in the night. The frustrated passengers of the

overcrowded trains rioted. They broke the windows of all the trains and

got off the trains in stations and marshalling yards, demolishing

buildings and passing trains and blocking the traffic. The last trains

from the airfield reportedly didn't reach Paris until three

o'clock in the morning. The Minister of Public Works would later in

the week order an inquiry into the cause of the failure in order to

find the responsible.

In contrast, everything worked smoothly for those who eventually got to

the airfield. The weather was fine and Gaudart, de Nabat, des

Vallières, Busson, Richet and Fournier made some short flights, but the

hero of the first Sunday was Paulhan. He took off at around four

o'clock and made the longest flight, completing eight laps

including a pass directly above the ecstatic spectators in the

grandstands. De Lambert then flew seven laps, followed by Gobron, who

flew four laps. Gobron never got up to full speed, since the

carburettor was partially blocked by sawdust collected during a test

run inside his hangar. Latham had a miserable day. He was caught up in

the traffic chaos and had to walk several miles to get to the airfield,

only to find out that his plane, a brand-new Antoinette VII built for

Capitaine Burgeat, wasn't ready. De Lambert won the Prix

Scheurer-Kestner for the best time over one 2 km lap at 2:09.0 and the

Prix de Neuflize for the best time over two laps at 4:18.6. This was

the second day for contesting the Prix du Conseil Général de la Seine.

De Lambert improved his time to 10:52.2 and Paulhan posted 13:37.8 to

place second. The Prix du Conseil Municipal de Paris was also a contest

in which pilots could make efforts on different days. It was a race

over one lap, in which the flyers had to cross the starting line at

less than eight metres above ground, pass over a balloon anchored at 40

metres and then cross the finish line at less than 8 metres. This was

the first day, and de Lambert placed first at 2:27.2.

Monday October 11th

The next day was another perfect day for flying, but as usual there was

no flying in the morning. In the afternoon de Nabat and Busson made

some short flights. Gobron had fixed his engine and flew a fast lap,

winning the day's speed prize with 2:12.2. Fournier had a very

close call when his Voisin got caught in the wash of Gobron's

plane. He lost control over his plane close to the place where the

course crossed the river Fausse Orge. He managed to clear the river by

a matter of yards and very narrowly missed some workmen and

photographers before hitting a bush, which broke some struts and wires,

swung the plane around and stopped it. De Lambert was the only flyer to

make a flight of any distance, covering six laps and thereby taking the

lead in the Grand Prix de la Société d'Encouragement à

l'Aviation, which ran for the first day.

Tuesday October 12th

The weather had taken a turn to the worse, with higher winds and risk

for rain. The crowd of around 40,000 waited patiently until four

o'clock in the afternoon before Paulhan brought out his plane. He

first made an attempt on the slow flight prize, covering the required

three laps of the 1.667 km course in 6:11.0. He then continued for

another sixteen laps, staying in the air for almost 40 minutes, again

flying above the grandstands and showing his complete command over the

airplane in the tricky conditions. While Paulhan was flying, de Nabat

made a good take-off in a new Koechlin plane with a more powerful 40 hp

Gyp engine, but suddenly nosed down right in front of the grandstands.

The plane hit the ground heavily, broke a wheel and ended up on its

nose. The accident was blamed on a failed rod in the elevator control

linkage. Gaudart also made a short flight, but the only other flyer to

complete a whole lap was Gobron, in 2:33.2. He had disassembled the

machine in order to take it to the more lucrative Blackpool meeting,

but the organisers put pressure on him to fulfil his engagement at

Port-Aviation so he put it together again, necessitating a test flight.

Fournier had also taken his machine apart, but would not let himself be

persuaded to stay. As a consequence the organizers, headed by baron de

Lagatinerie, had two policemen posted outside his hangar to stop him

from removing the plane. Latham had by now spent three days at the

airfield, waiting for his Antoinette to be put in flying order. In

increasingly bad mood he watched as the mechanics tried to make the

brand-new engine run, which hadn't even run on a test stand before.

Wednesday October 13th

The strong and gusty winds continued, but otherwise the weather was

better and there was a little bit more flying. However, there was none

of it until at around four o'clock, when Burgeat's #37

Antoinette was rolled out for Latham. He made a good start and rounded

two pylons, but then a wing dropped and it seemed like the engine

missed. Latham made his best to make a safe landing, but landed on only

the left wheel and the left wing tip hit the ground. The plane came to

a halt, dragging its crumpled wings on the ground. This was a bitter

disappointment for Latham, since he wanted to show the Parisians what

he could do before leaving for Blackpool, where his usual plane had

already been sent.

De Lambert and Paulhan each flew four laps, the latter testing a new

big fuel tank that he hoped would help him win the distance prize.

Paulhan's 9.4 km flight elevated him to second in the Grand Prix de

la Société d'Encouragement à l'Aviation, behind de Lambert, but

there were still two days left. Gobron flew a single lap in 2:17.2,

beating de Lambert's fastest lap of 2:24.8 to win the day's

single-lap prize. Busson finally managed to complete a lap in the WLD,

but only by landing and taking the turns rolling on the ground! Gaudart

tried to make a test flight, but failed to take off and while taxiing

back to the hangar area he rolled into a fence, destroying a wing on

his Voisin.

Thursday October 14th

This was the big day of the meeting, when the French president Armand

Fallières came to visit. He arrived at 15:30, accompanied by military

escort and music, and was received by Baron de Lagatinerie, Comte

Jacques d'Aubigny, and the organisation committee. Just as in

Reims, the president arrived on a day when high winds made flying

almost impossible. However, Latham's plane had been repaired after

the crash of the day before and was rolled out. He took off in great

style, but his engine failed again after only half a lap, causing

another forced landing. This time the damages were limited to a bent

landing gear, but they still put him out of action for the rest of the

day. Also like in Reims, it was Paulhan who was able to show the

president some flying, completing three laps before leaving the

airfield for a short trip out of sight over Juvisy. After returning to

land he was taken to the president, who shook his hands and

congratulated him amid great ovations. De Lambert tried to take off,

but on leaving the starting rail his Wright turned and landed sideways.

The crash broke the right wing and the skids of the plane, but de

Lambert was unhurt. Gobron had fine-tuned his engine and made a lap in

1:56, the fastest recorded so far during the meeting, before flying six

more laps. Later in the evening when the winds had calmed down, Paulhan

flew eleven more laps, and also won the altitude contest at 150 m.

Friday October 15th The first serious accident of the meeting

happened in the morning. Richet had modified his Voisin by removing the

vertical "curtains" between the wings and changing the fuel

tank, and had made a couple of straight test hops during the early

morning. Against the advice of other flyers, who were worried about the

stability of the plane, he took the machine for a longer flight at

8:40. After one lap in a wind of 4 m/s he lost control of the plane in

a turn and hit the ground heavily on the left wing, from an altitude of

around ten metres. The plane turned into a tangled mess of broken

struts, fabric and wires and Richet was carried unconscious to the

ambulance station. Although he hadn't broken any bones he had been

concussed and badly cut and bruised, having his left ear torn off and a

leg badly sprained.

After the relatively calm morning the high and gusty winds returned on

the afternoon, so Paulhan wasn't able to use his new fuel tank to

make an attack on the distance contest. To the relief of the

enthusiastic but anguished spectators he decided to give up after

fighting the gusts for five laps, sometimes recovering from banks of 45

degrees. The exhausted Paulhan declared that he had never flown in such

difficult conditions. He had decided to leave a day later than planned

in order to try to win the prize, but now he was going to Blackpool to

fly his new Farman. This meant that de Lambert won the prize with a

flight of only 13 km. After more repairs, Latham came out for another

effort later in the afternoon, but his engine failed immediately.

Saturday October 16th

The strong winds continued. Baratoux rolled out his Wright, which was

equipped with wheels that enabled starts without the use of the usual

Wright rail, but he couldn't do anything. The only one to fly was

Latham, who finally managed a successful flight despite the awful

conditions. He gave up after a brave fight over two laps, again to the

relief of the 10,000 spectators, who had seen him being tossed about at

seemingly impossible angles.

Sunday October 17th

Around 100,000 spectators visited Port-Aviation on the day of the

Aéro-Club de France. The day started windy, but the weather improved

during the day and around 4pm de Lambert made a first flight of nine

laps. The unlucky Latham made a new try, but after two laps his engine

again failed and his landing gear was damaged when the plane was pulled

out from soft ground. Gobron made a flight of four laps, so de Lambert

won the day's distance prizes. At dusk, after official closing

time, Gaudart made a flight of one or two laps in the light of Bengal

fires, "the effect being very picturesque" according to the

reporter from The Aero. Brégi (in Paulhan's #27 "Octavie

III"), Busson, Baratoux and Bonnet-Labranche also made short

flights.

Monday October 18th

The morning started with novice pilot Florencie (not entered in the

competitions) standing his biplane on the nose, breaking the propeller

but without injury to himself. Then Busson made a heavy landing from an

altitude of 10 metres, also escaping injury. In the afternoon Gobron

flew four laps, followed by another accident when Koechlin landed

heavily, broke his propeller and was thrown out of the plane, again

unharmed. The longest flight of the day was made by Henri Brégi, who

made his competition debut by flying ten laps in Paulhan "Octavie

No. 3".

The day ended with a bad accident caused by novice pilot Guy Blanck,

who was not entered in the competitions and had taken delivery of his

Blériot only 18 days before the meeting and made his first flight at

Issy-les-Moulineaux on October 1st. His total flying experience could

probably be measured in minutes rather than hours when he took to the

air at around 17:00. After a good takeoff his plane swerved towards the

grandstands. He apparently froze at the controls and hit the fence

without having cut the engine. A woman, Mme. Féraud, who stood at the

fence, was "literally stripped by the propeller and had her left

thigh and calf cut to the bone", according to the reporter from

"La Vie au Grand Air". Three or four other spectators were

also injured. Mme. Féraud, together with a M. Hanot, later sued Blanck,

Baron de Lagatinerie (as responsible for the event) and the societies

behind the meeting for damages of 100,000 francs as compensation for

her injuries. The final verdict was reached on June 17th, 1910. The

court stated that no laws had been broken, since there were no

regulations for safety at airfields and, at the time, no licensing

system for qualification of pilots. In view of the fact that aviation

was at an early stage of its development and was an obviously dangerous

activity neither Blanck nor the organizers were found guilty of

culpable negligence. Therefore the court acquitted them and made Féraud

and Hanot pay the legal costs.

Even though there were several accidents and incidents the day is not

remembered for what happened inside the fences of Port-Aviation, but

rather outside. At 16:37 de Lambert took off in his Wright. He circled

a couple of times over the field to gain altitude and then left the

airfield in the general direction of Paris. He had reportedly only told

two people about his intentions, so when he didn't return

immediately people at the airfield started to believe that he had

crashed somewhere in the surroundings. He had in fact steered towards

the centre of Paris, flying higher and higher above streets and

buildings. When reaching the Eiffel Tower he turned around it, at an

altitude estimated to be around 100 metres above the 300 metre tower,

then the highest building in the world. This was far higher than the

official world altitude record, which stood at 172 metres. He then

returned back to Port-Aviation and landed elegantly only metres from

his hangar, to the relief and ovations of the by now very worried

crowd, which included Orville Wright, who happened to be there. The

flight, which was estimated to 45 or 50 km, had taken 49 minutes and

49.4 seconds. It didn't count for any of the competitive events

during the meeting, but it was soon decided that de Lambert would be

given a gold medal by the LNA for his achievement.

De Lambert's flight was celebrated as one of the greatest flights

ever, but there were also many, including Orville Wright, who thought

it was an irresponsible stunt that had endangered the lives of not only

the count himself, but also his fellow men. The reporter from "The

Aero" wrote that "like the Channel flight, it will be done

again and again, and unless stopped by legislation, someone will be

killed at it, but de Lambert was and remains for over the first man to

do it. Therefore, all honour and glory to his performance, though he

deserves permanent disqualification from all future competitions for

having done it".

Tuesday October 19th

The main event of the day was the Prix Paul Crétenier, for the fastest

2 km lap at a height of at least 15 meters. This was won by Gobron at

2:02.8, while de Lambert managed 2:03.0. This was the closest possible

margin, since the stop-watches of the day only measured time to a fifth

of a second! In the morning the new pilot Georges Copin appeared for

the first time with a big Anzani-powered biplane of his own design. In

the afternoon Gaudart made a short flight which ended in a heavy

landing that wrecked the landing gear and right wing of his Voisin. The

longest flights were made by Brégi (eight laps, 21.405 km), Gobron (six

laps) and de Lambert (five laps). This was the third day of competition

for the Prix du Conseil Général, and Gobron posted a time of 10:45.4 to

take over the second place. At the end of the day Brégi took Mlle.

Jeanne Laloë, writer for the newspaper "L'Intransigeant"

for a lap. It was announced that the meeting would continue until the

weekend in order to compensate the Parisians for the missed days.

Wednesday October 20th

This was the last day to compete for the distance prizes, but due to

high winds there was no flying until 16:30. The first to try was Busson

in the W.L.D., but he only managed a short hop. Brégi rolled out

Paulhan's Voisin, but landed after one lap. De Lambert made a

flight of two laps carrying a count de Malynski, who had bought a

Wright plane, as passenger. Since the bad weather didn't allow much

flying nobody could improve their times.

Thursday October 21st

During the morning the decision made two days before was reversed and

it was decided that this would be the last day of the meeting. The

reason for the cancellation of the last days was stated to be problems

policing the ground. The weather was calm, so even the less experienced

flyers could fly, for example de Nabat, Koechlin, Baratoux and Gaudart.

Gobron equalled his best lap of 1:56, matching the fastest times posted

by de Lambert. His unique Gobron-Brillié engine, with eight cylinders

in X configuration and two pistons per cylinder, must have been in top

shape, since the Voisins were normally no match for the Wrights in a

race. In the afternoon Brégi made the longest flight of the meeting, 13

laps in 33:03.8. While he was flying, de Lambert flew six laps, the

first which counted for the Prix du Conseil Municipal de Paris. He

improved his time to 1:56.8 to win the prize. After de Lambert's

landing a closing lunch was held, during which he was given a gold

medal celebrating his flight over the Eiffel tower.

Conclusion

The "Grande Quinzaine" was a huge crowd success and gave

hundreds of thousands of Parisians their first chance to see an

aeroplane. With the exception of the disastrous train services during

the first weekend, which of course couldn't be blamed on the race

management, the event was also considered an organizational success.

However, from a sporting point of view it didn't deliver much apart

from de Lambert's famous flight - which was not even part of the

program!

The overly extended program and the competition from other well-paying

events probably made the experienced pilots save their planes and avoid

risks. 43 planes were entered, but only six pilots (de Lambert,

Paulhan, Gobron, Latham, Brégi and Gaudart) actually claimed the 500

francs prize for completing a lap of the course. Despite the high

number of competitions the prize money was split between only four

pilots, and many prizes were not awarded. The longest flight lasted

less than 40 minutes.

This was the last meeting of the 1909 French flying season, but

meetings were still going on in England and Belgium.