Port-Aviation (Juvisy), France, 23 May 1909

Prix de Lagatinerie, May 23rd, 1909 - The world's first air race

The history of the world's first air race can be traced to July

30th, 1908, when the "Société d'Encouragement à

l'Aviation" was created. This society, founded by Dr.

Charles-François Dussaud, had three objectives: the creation of the

first airfield, the first flying school and the first aviation

contests. The society found a site for its airfield in the commune of

Viry-Châtillon, a rural village of 2,000 inhabitants some 15 kilometres

south of central Paris. It was a park of some 100 hectares, owned by

the widow of Jean Alexis Duparchy, an engineer who had made a huge

fortune during the construction of the Suez Canal and of railways in

several countries and died in October of 1907. The park would be easy

to convert to an airfield and had two railway stations (Juvisy and

Savigny-sur-Orge) within walking distance.

The society wasted no time after renting the park. A company, the

"Compagnie de l'Aviation", was formed in order to operate

the field. Construction work started immediately and hangars and

grandstands were built. The flying school was founded on November 1st,

1908, financed by a donation of 5,000 francs from Baron Charles de

Lagatinerie and with Capitaine Ferdinand Ferber as its first teacher.

The first flights at "Port-Aviation", as it had by then been

named, were made on November 20th by Léon Delagrange, in the presence

of Wilbur Wright and some 2,000 spectators. It had originally been

planned to hold the opening ceremonies on January 10th, but the

infrastructure was not ready. On April 1st a ceremony was held where

the airfield and the school's two Voisin planes were officially

blessed by the Archbishop of Paris.

The official opening of the Port-Aviation airfield was finally made on

May 23rd, 1909. The event was broadly announced in newspapers and on

posters, with the result that a crowd that was estimated to between

30,000 and 60,000 people gathered on the airfield, expecting to see the

most famous aviators compete against each other.

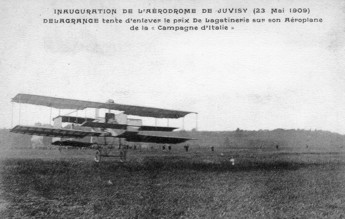

The main event of the inauguration program was the 5,000 francs

"Prix de Lagatinerie". The name of the race was that of its

donors - there were two men of that name in the committee of the

organizers "La Société d'Encouragement à l'Aviation",

the two barons Charles and Bernard de Lagatinerie. The prize was

offered to the pilot who covered 10 laps of a 1.2 kilometre (0.75

miles) course in the shortest time. In case nobody completed the full

distance the winner would be decided by the longest distance covered.

The course was marked by two pylons, 600 metres apart. Stops were

allowed, and would be included in the total time. The contest would

start at 14.00 on May 23rd, 1909.

Nine pilots had entered and paid their 100 francs entry fee by the May

17th deadline. However, only four actually showed up:

- Léon Delagrange on the Voisin "Delagrange No. 3"

- Henri Rougier on a Voisin

- Alfred de Pischof on a de Pischof et Koechlin

- "F. de Rue" (pseudonym for Capitaine Ferdinand Ferber) on a Voisin

The five entrants who didn't turn up were two pilots from the French Wright licensees Ariel (presumably Paul Tissandier and Charles de Lambert), Paul Koechlin (de Pischof et Koechlin), Raoul des Vallières (Voisin) and Henri de Puybaudet (Voisin).

The weather on May 23rd was unseasonably hot and when the race was planned to start there was a wind of 3-4 m/s (7-9 mph). These wind speeds would not in themselves have created any problems, but the wind was blowing across the strip that had been mowed in the tall grass, so the start had to be postponed. If the entire field had been mowed so that the planes could take off in any direction there would not have been any problems The spectators had not been informed that the planes would not be able to fly if it was too windy, and they were getting impatient. In order to keep the crowds entertained a kite contest was started instead, which lasted for two hours.

However, the crowd had come to see airplanes, and they were not amused by waiting in the baking heat. The situation started to get difficult, so at 16.15 Delagrange rolled out his Voisin out in order to give the spectators something to look at. At the same time the crowd broke through their enclosure and charged into the field. They quickly surrounded Delagrange and his plane, but at 17.15 he was eventually allowed to fly a lap around the field. The crowd cooled down a little when they actually got to see some flying, and it was announced that the race would start later in the day.

The race finally started at 17.45. The first to start was de Pischof, despite having previously decided to withdraw. However, he could not lift off and stopped after only a couple of hundred meters and took no further part. Delagrange was next in line at 18.20, but already during the rollout he had to abandon his effort due to broken elevator controls. At 18.45 it was Rougier's turn. He took off, but on the back straight of the first lap, flying very low, he had to veer in order to avoid a couple of spectators who had been lying in the tall grass and suddenly stood up. He hit the ground and put his plane on the nose, luckily without any injuries and, thanks to the plane being a pusher, with only minor damage.

While Rougier's plane was retrieved Louis Lejeune, who was not entered in the race, tried to fly his plane. This was a small twin-propeller pusher biplane, somewhat similar to a Wright. It was built by de Pischof et Koechlin and powered by a 12 hp three-cylinder Buchet engine. However, despite very long ground runs through the grass the plane never managed to take off, it only earned itself the nickname "la moissoneuse" (the harvester).

At 19.10 Delagrange made another effort. Since his own plane couldn't be repaired quickly he had asked for permission to use one of the flying school's Voisins instead of his own. After some fierce discussions he was given permission to use the Voisin "L'Alsace", on the condition that he paid 4,000 francs of the prize money to the LNA if he won. He made his first lap at an altitude of 5 meters, but later reached 15 meters (50 feet). He managed almost five laps, a total of 5,800 meters (3.6 miles) in 10 minutes 18.6 seconds before he had to land. His average speed was 33.75 km/h (21.0 mph. This sounds incredibly slow, but the 5,800 meters was the geometrically calculated distance back and forth between the two pylons and the actual distance flown was of course much longer. Delagrange actually had no hope of completing the race distance, since the engines of the school's Voisins were not equipped with radiators and could not be expected to run more than 10 minutes before the water in the coolant header tanks started to boil. Rougier had quickly repaired his plane and intended to make another try, but by then the wind had risen again, making further flying impossible. Since de Rue had already withdrawn that was the end of the flying.

Conclusion

Everybody except the most enthusiastic aviation writers regarded the race as a fiasco. When announcing the start of the race for 14.00 the organizers had not taken note of the fact that almost all flying in those days was done in the calmer air of early mornings or late afternoons . There was no alternative program organized in case there could be no flights. The dusty roads to the airfield were jammed with automobiles, horse-carriages, bicycles and pedestrians. The trains were full and didn't stop to take on passengers. Information and services at the field were insufficient. The airfield was not fenced in and there were not enough policemen to keep the unruly crowd in order. The bars and restaurants where overwhelmed and ran out of drinks.

The organizers learned some hard lessons, but they soon used their experiences for staging further meetings.