Los Angeles, USA, January 10th - 20th, 1910

The first aviation meeting in the USA

Aviation meetings, and aviation industry in general,

were slow to take off in the United States. One of the

reasons was that the Wright brothers had been granted a

patent which gave them exclusive rights to some aspects

of airplane control, particularly roll control by wing

warping. They threatened litigation against anybody who

built or displayed airplanes.

This did not stop people from trying. A couple of minor

displays were held during 1909, and in connection with

one of them, the 12-14 November Cincinnati meeting

(actually held in nearby Latonia, Kentucky), Glenn

Curtiss' partner Charles Willard met Roy Knabenshue,

who made exhibition flights in his little airship. They

agreed to try to organize something in Los Angeles during

the winter, and got support from Curtiss. In 1910 Los

Angeles had a population of more than 300,000. After

having been a mere village during the mid-1800s the

population had grown enormously, driven by improved

communications and a huge increase in trade, mainly in

fruit but also in petroleum and industrial products. The

population had tripled during the last three years.

Willard and Knabenshue contacted Dick Ferris, a Los

Angeles businessman and balloon enthusiast who had

participated in organizing similar events before. He put

the idea forward to the Los Angeles Merchants and

Manufacturers Association, who promised to raise the

necessary funds, for example a prize fund of 80,000

dollars. Curtiss and Willard visited possible sites and

settled for the Dominguez Hill, close to Compton some 20

kilometres south of Los Angeles. This site had several

advantages: It was close to the railway, it was free from

obstructions and it was situated on a low mesa, so that

anybody who wanted to see the action would have to pay

the entrance fee. Furthermore, the owners of the site,

the Dominguez family, let them use it for free. An

engineer, S. B. Reeve, was hired to prepare the site,

construct the grandstand and build pylons to mark the

course. A committee consisting of Dick Ferris, US Aero

Club president Cortlandt F. Bishop, Edwin Cleary and

Jerome S. Fancuilli, took care of the program and

rules.

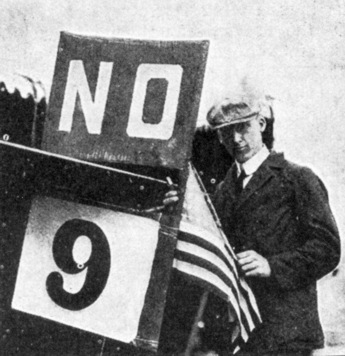

An early list of entrants contained 43 airplanes and six

airships, but in the final program the number was down to

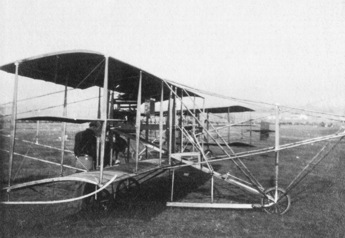

eleven and three respectively. The Curtiss team would

bring four planes, to be flown by Glenn Curtiss, Charles

Willard, Charles Hamilton and Clifford Harmon. The latter

in fact took delivery of his brand new plane at the

meeting and was to receive flight training there. The

Wright brothers did not participate and there weren't

many other American aviators around, although several

optimists would bring their untested constructions to the

meeting.

In order to get a more international status Louis Paulhan

was invited. He accepted, no doubt attracted by the

generous offer of a reported 150,000 francs for a

three-month tour, and started to build up a team. In

addition to his two Farman planes he bought two Blériot

XIs and spent three days in the beginning of December at

the Blériot flying school in Pau in southern France

learning to fly them. Paulhan would travel in company

with his wife, their black poodle, his business partner,

a marquise (or baron, depending on your sources) with the

fantastic Breton-sounding name of Robert de Kersauson de

Pennendreff, and his wife. The team included two

mechanics, Didier Masson and Charles Miscarol, who were

also entered as pilots but had actually flown very little

before leaving France.

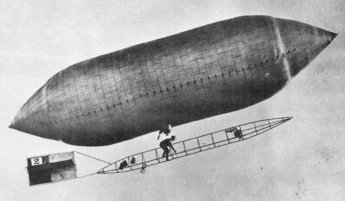

Three airships were entered, the two small "racing

dirigibles" of Knabenshue and Lincoln Beachey and a

US government ship, which in the end never appeared since

it could not be filled at the airfield. There were also

competitions for balloons, which were not held at the

airfield, but at Huntington Park, some 10 kilometres to

the north. Seven balloons were entered and made regular

flights during the meeting, but the new-fangled, exciting

airplanes got most of the attention from the press and

the public.

When Paulhan arrived in New York he was immediately

served with an injunction from the Wright brothers, who

wanted to forbid all his flights in the USA because the

control systems infringed their patents. He received a

second injunction in Denver, Colorado, on the way to Los

Angeles. The suit was due to be heard in court, but the

hearing was adjourned to January 28th, so in the interim

Paulhan could participate in the meeting. The Wrights

demanded all the profits from Paulhan's flights plus

three-fold damages, since they claimed Paulhan's

flights would destroy the novelty of flying machines.

This was stated to be a big loss to the Wrights, since

public desire to see machines in flight would be

satisfied before it would be possible for the Wrights to

display their planes.

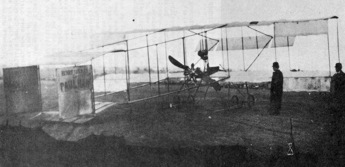

Monday 10 January, "Aviation Day"

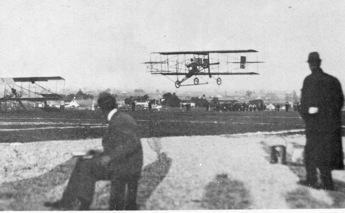

The weather was perfect on the first day of the meeting,

sunshine and only a light breeze. A crowd of around

20,000 people waited patiently for the first flight in

the West. Curtiss had made a couple of short test hops in

Harmon's brand new plane the day before, but they

could hardly count. At one o'clock Curtiss finally

rolled out Harmon's plane and made a flight of one

and a half minute, covering around one kilometre. Willard

was the second to fly soon afterwards, flying a mile in

1:23. Paulhan decided to show off a little and taxied

away from the grandstands out of his tent hangar, which

faced away from the grandstands and was hidden from view

by the Curtiss hangar. He then took off out of sight

while the crowd was looking at the dirigibles of

Knabenshue and Lincoln Beachey and suddenly appeared at

full speed in front of the crowds. Paulhan, showing

"brilliant daring", was the only flyer to

complete a whole lap of the course during the first day,

making three flights of totally around 30 kilometres.

During one of them he easily overtook Knabenshue's

airship, travelling around twice as fast. Curtiss made a

second short flight in his V8-powered "Rheims

Flyer", breaking his propeller when landing in an

uneven spot. Hamilton also made a flight of 1.5 miles in

his four-cylinder Curtiss. The engine of the Gill-Dosh

machine, to be flown by Hillery Beachey, brother of

Lincoln, "exploded" in the hangar and damaged

the top wing. Several flyers complained of the fuel

provided, which was claimed to be "muddy" and

cause the engines to overheat. Better fuel was promised

for the remainder of the meeting.

Tuesday 11 January, "Los Angeles

Day"

Heavy rain during the night before made the roads muddy

and caused many cars to get stuck in the access roads. A

large work force was sent out to improve the roads with

straw and planks. The second day of the meeting started

windy, with gusts of up to 20 m/s. Towards the afternoon

Paulhan made three flights, the longest of some 15

kilometres, and he also made a passenger flight.

Otherwise the afternoon was spent on take-off and

precision-landing contests. At the Los Angeles meeting

the participants were free to try for the different

events whenever they wanted, and since these contests

didn't require a lot of flying they were preferred on

a windy day. Curtiss took the lead in the shortest

take-off contest by starting in 29.9 m, while Paulhan in

his Farman needed 56.2 m. Curtiss also made the quickest

take-off. His time was 6.4 s from the first explosion of

the engine to leaving the ground, while Paulhan could

only manage 12.4 s with the Farman and 35.0 s in one of

the Blériots. Curtiss' results were both claimed to

be world records. In the precision-landing contest

Willard was the only one to make a perfect landing inside

the 20 foot square target.

Paulhan's Blériots were flown with their wing-warping

mechanisms disconnected. This was in order to respect the

Wright patent, which didn't clearly cover ailerons,

but definitely covered wing-warping. This of course

limited their performance and made them difficult to

control. Paulhan's inexperienced trainee Miscarol

tried to make a flight, but after a slow flight of around

1.2 km he was caught by a gust and broke a wheel in the

resulting rough landing. Paulhan, perhaps eager to show

that it was possible, took out the other Blériot for a

flight of some 3 km.

The wind decreased during the afternoon, allowing Curtiss

to take his business manager Jerome Fanciulli for a

flight of around 1.6 km. During the flight he was

measured to make 55 mph (88.5 km/h), which was faster

than the world speed record. In a couple of European

magazines this was misunderstood and it was claimed that

he had set a fantastic new record by making a one-hour

passenger flight of 55 miles.

There were more accidents and incidents. Hamilton got too

low during a short test flight and hit the ground,

breaking his elevator. Professor Zerbe tried to make a

flight in his five-wing plane, but just when he reached

take-off speed a drive chain broke. The plane fell to one

side, breaking a wheel, a propeller and the lower wing

tips. The professor thankfully escaped injury. A much

more dangerous incident happened in one of the hangar

tents. Edgar Smith was doing an engine test on his

tandem-wing monoplane and accidentally got into to the

turning propeller. He was thrown more than ten feet by

the impact and the metal propeller was folded double. He

must be considered lucky to have got away with a

five-inch cut on the back of his head and badly bruised

arms. After being transported to his home in

"delirious and hysterical" condition he was

back later during the week, with his head in a

bandage.

Wednesday 12 January, "San Diego

Day"

Five days earlier, on January 7th, Hubert Latham in his

Antoinette had raised the world altitude record to 1,050

m at Mourmelon in France. Paulhan was of course keen to

better this mark, and especially so in view of the bonus

prizes to be paid for world records. The third day of the

meeting was a very promising day, clear and with little

wind. During the afternoon Paulhan made his previously

announced effort for the altitude prize and the world

record. For 43 minutes he circled ever higher and after

the landing seven and a half minutes later the barometric

altimeter carried on the plane indicated an altitude of

4,600 feet (1,402 m). This figure was not approved by the

committee, since the altimeter was not considered

accurate because of the inconsistent atmospheric

conditions and its exposure to the vibrations of the

engine. The trigonometric calculations performed by

students of the Polytechnic High School indicated that

the altitude reached was 4,165 feet, equivalent to 1,269

m, and these figures were the finally approved.

There was also action around the pylons. Curtiss started

by flying a 2:13.6 lap with Harmon's machine. He then

continued by improving the time to 2:12.4, this time

flying Willard's "Golden Flyer".

Paulhan's Farmans could not match these times, his

best lap was 2:25.6. Paulhan also made a five-lap run,

but the time of 12:23.2 was unofficial, since there

weren't pylon judges at all pylons. Hamilton had

persistent engine trouble but finally managed to complete

a lap of the course and a short cross-country trip.

Harmon made his maiden flight in his new Curtiss, a short

hop around 30 meters.

Thursday 13 January, "Pasadena Day"

The Thursday was another clear day and the spectators got

to see a fair bit of flying. In the morning Hillery

Beachey took out the repaired Gill-Dosh for a test, but

broke one of the lower wings when he came to earth in

rough ground. Beachey was uninjured, but the machine

would require new repairs. Paulhan carried eight

passenger, among them his wife and Mrs. Ferris, wife of

the meeting organizer. He also carried both his

mechanics/trainees Miscarol and Masson during a flight.

Both Curtiss and Paulhan made efforts for the 10-lap

speed contest, Curtiss beating Paulhan by only five

seconds, 24:54.4 to 24:59.4. During Curtiss' flight

Paulhan cut in before him which made Curtiss' plane

drop dramatically in the wash.

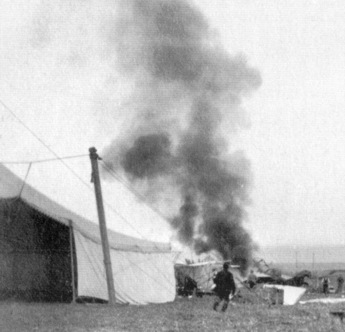

In the hangars there was a dramatic incident when the

Klassen "Butterfly" monoplane caught fire. All

the fabric was burned off, and the fire threatened to

spread to the Paulhan camp before bystanders could put it

out. Willard made another perfect effort for the

precision take-off and landing contest by taking off and

landing in the same 20-foot square.

Friday 14 January, "Southern California

Day"

Another beautiful day and another spectacular flight by

Paulhan. He again took off out of view from the

grandstands and after buzzing them he left he airfield in

the direction of the coast. He flew to San Pedro and

circled the fortifications of Point Firmin and the

harbour, where he was greeted by ship steam whistles and

bells. The flight was estimated at some 33 km. After

landing Paulhan remarked that he could easily have

bombarded the fortifications. On the airfield several

pilots tried for a quick lap. Curtiss improved his best

time to 2:12.0. Paulhan made the lap in 2:21.2, while

Willard made two laps with a best of 3:01.4 in his

Curtiss, which had a four-cylinder engine of half the

power. Paulhan made a lap in 2:48.0 in one of his

Blériots. This was the only official lap made by a

monoplane during the entire meeting.

Curtiss carried Lieutenant Paul Beck of the US Army as a

passenger in order to try to bomb a target on the ground

with bags, but engine trouble caused them to abort and

postpone the test. Paulhan took Masson for an 18-minute

dual-instruction flight in the Farman, covering six laps

of the race course. He then took Courtland F. Bishop, the

president of the US Aero Club, for a flight. The flight

must have made some impression on the balloonist Bishop,

who lost his borrowed cap during the flight and held on

to the struts with such force that they reportedly had to

be pried off after the flight. Getting off, he then got

so entangled in the rigging of the plane that he needed

help to be released.

Roy Knabenshue posted a best lap time for dirigibles with

5:10.4, and won a race with Lincoln Beachey in 6:29.6

versus 7:50.0. Even though slow, with a top speed of only

30-35 km/h, the small dirigibles were popular with the

crowd, since the pilots had to climb acrobatically around

their "nacelles" in order to keep their ships

balanced. Towards the evening the spectators were treated

to the spectacle of seeing three biplanes, two dirigibles

and one balloon in the air at the same time. This was one

of the most successful days of the meeting. It was

estimated that a total of 50,000 spectators were present,

bringing 5,000,000 dollars worth of automobiles.

Saturday 15 January, "San Francisco

Day"

After the fine weather of the beginning of the meeting

the weather turned worse, with rain clouds drifting in

from the sea. After a miserable morning the weather

improved during the afternoon and Paulhan was first to

fly. He again took off out of sight before buzzing the

grandstands twice, the second time with an unlit cigar in

his mouth. Hamilton was next to fly. While he was

completing the third lap of a planned ten-lap run Paulhan

took off and tried to make a race with the much slower

Curtiss. He quickly reached him and dived down to pass

Hamilton from below. Hamilton was thrown far off course

by the wash and was for while heading towards the

grandstand before regaining control. He eventually

completed the ten laps in 30:34.6 with a best lap time of

2:57.6, but after a second similar event Paulhan was

getting unpopular with the other flyers for interfering

with their flights.

Knabenshue in his dirigible also tried to prove the

possibilities of aerial warfare by bombing the 20 foot

precision landing square in front of the press boxes. He

managed to maneuver above the square and throw his bags

of earth accurately, but at an altitude of 20-30 meters

he would have been an easy target, and the ship would

probably have been blow to bits if real explosives had

been used.

Curtiss, Paulhan and Willard made one-lap qualifying

flights with times of 2:19.4, 2:33.8 and 3:03.4

respectively. Hamilton also flew a lap, but the time

isn't known. Towards the end of the afternoon

Miscarol took out one of the Blériots for engine tests.

He was running back and forth on the ground at relatively

high speed along the back straight of the course when he

suddenly lost control of the plane after a turn. After a

couple of wild swerves the left wing hit the ground and

crumbled and the plane came to rest on its side with

broken landing gear and propeller. The accident happened

far from the grandstands and the hangars. Miscarol had

knocked his head during the crash and was found running

around dazed and confused. He fortunately escaped with a

bruised forehead. The accident was blames on the Wright

brothers, since the Blériots had to be flow with their

wing-warping mechanisms locked.

Sunday 16 January, "Special Day"

This day also started rainy and the rain didn't stop

until around two o'clock. Although improved, the

roads were still difficult and some auto parts dealers

were making good business selling anti-slip chains. It

was still windy, though, and when Hamilton tried to fly

for the endurance flight he was blown off course and had

to land. Curtiss, Paulhan and Willard all tried to fly,

but all gave up after a lap or two. Curtiss estimated the

wind to 10 m/s (more than 20 mph) and said that even

though he was holding back he travelled along the

grandstands at 100 km/h (more than 60 mph). Paulhan tried

for the short take-off prize and improved his result to

36 meters, but not enough to beat Curtiss. Hamilton set a

time of 9.2 s for the quick take-off prize, but again not

enough to beat Curtiss. Towards sunset the wind decreased

somewhat and Paulhan made a passenger flight. The two

dirigibles also flew, but pitched and rolled and could

make very little headway against the wind, so they were

soon retired to their hangars again.

Paulhan created a minor incident in the evening by not

appearing at a dinner held in his honour by 80 members of

the Cercle Coquelin, a French society of Los Angeles. He

was dining with his friends at another restaurant and his

manager had to be sent to apologize for his failure to

appear.

Monday 17 January, "Free Harbor Day"

The rain had stopped and the morning was clear and

bright. In the morning Curtiss made several flights, one

of them with Lieutenant Beck of the US Army as passenger,

a second with Frank Johnson, a trainee pilot. He also

made a speed run of one lap in 2:18.8. Paulhan made a

test flight. At 2:15 Paulhan took off, trying for the

endurance record. It was speculated that he had enough

fuel to fly for twelve hours. When Paulhan had flown for

50 minutes Hamilton decided to also go for the endurance

prize. Paulhan's Farman was slightly faster than

Hamilton's four-cylinder Curtiss and caught up with

him and overtook him. Hamilton's plane "rocked

and swayed and rolled like a channel boat in a heavy

sea" in the wash. Willard was watching

Hamilton's flight through binoculars and noticed that

a wing strut was hanging loose and a wing tip was

flapping, so the next time Hamilton passed he was flagged

down. After landing it was found that a bolt had worked

loose and the right rear wing strut had slipped from its

socket. He had been in the air for 39:00.4 and had

travelled 31.3 km. Paulhan also ran into trouble. A smell

of gasoline was felt every time he passed and a fuel leak

was suspected. He came down to land after 1 h 58:32.0 in

the air, having covered 121.9 km at an average speed of

61 km/h, and it was verified that there was a leak in a

fuel line. He then made a flight in his other Farman

before trying Willard's Curtiss. This was not a

success and the rough landing after a very short flight

broke some rigging wires and fittings.

Curtiss again tried for the 10-lap record, improving his

previous best with more than a minute to 23:43.6.

Paulhan's training flight with Masson in the Farman

three days before had apparently paid off, since Masson

managed a good solo flight around the course. Hillery

Beachey made two successful short starts in the Gill-Dosh

plane, but broke the landing gear on the last landing,

giving the mechanics further work to do.

Tuesday 18 January, "Ladies'

Day"

On the ninth day of the week temperatures dropped. Cool

wind from the north brought clear air, some small clouds

and single-figure temperatures in the morning. There

wasn't much activity in the hangars. At one

o'clock a Curtiss machine was rolled out, waiting for

the wind to allow a take-off, but nothing happened. One

of the balloons from the Huntingdon Park balloon field,

the "New York", carrying George Duesler, George

B. Harrison and Charles Willard, managed to fly up to the

airfield. They landed at the west end of the field and

the balloon was towed to the center of the field and

anchored there, ready for Clifford Harmon, who planned to

try to set an official balloon height record.

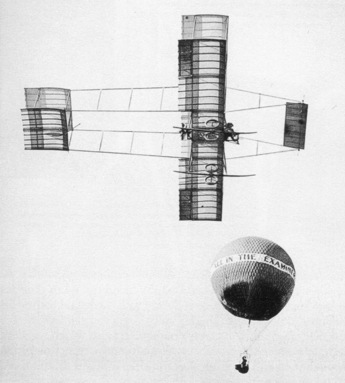

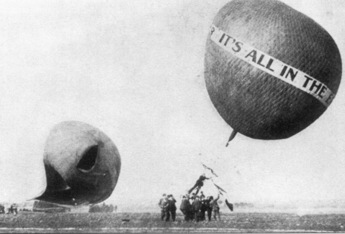

At around two o'clock the wind suddenly changed from

north to west and increased to gale force. This caused

frantic activity on the field. The Curtiss machine was

quickly rolled back into its tent. Many hands helped in

pulling down the "Examiner" balloon, which had

been tethered at the field during the entire week. E. J.

Spencer, a photographer from the Los Angeles Examiner was

in the basket and kept taking photographs while the wind

blew the balloon to the ground. The anchor rope held and

Spencer could get out after the balloon had been drawn

down to its anchor post. It was probably lucky that he

was there, since without his weight the balloon might

have broken its mooring line. The much bigger "New

York" was in a much more dangerous situation. Some

of the rigging broke while it strained on its lines and

the bag became loose in the net. Clifford Harmon finally

had to pull the rip cord to split the side of the bag and

release the gas. The loose fabric collapsed to the ground

but the $5,000 balloon was saved.

The wind was still estimated to around 13 m/s at three

o'clock when Paulhan rolled out his Farman and flew a

lap. Undeterred by the wind, which blew at around three

quarters of the top speed of his plane, he took off again

at 15:08 and after circling the field left it and headed

towards the north. The bulletin board announced

"Paulhan will fly to Baldwin's Ranch and return,

45 miles. Back in an hour". Many cars followed the

flight, and in one of them "Madame Paulhan mingled

prayers and shouts of joy, while tears coursed down her

face", according to a melodramatic newspaper report.

Information about his progress was telephoned in and was

progressively reported on the bulletin board. After 30

minutes he had reached Arcadia and circled the Santa

Anita race track, before turning back toward the

airfield, rising to around 640 metres. After a wide

circle through Huntington Park in the eastern part of Los

Angeles he could be spotted from the grandstands again.

The band played the Marseillaise as he landed after being

in the air for 1 h 02:42.8 and covered an estimated 76

kilometres. The crowd raised him to their shoulders, but

he asked to be let down so that he could retire to his

hangar. When the wind had calmed down in the afternoon

Curtiss tried twice to improve his record for short

take-off distance, but failed. Hamilton also tried, and

reached 47.2 m. This was the last flight of the day.

During the evening the Pasadena society organized a

charity ball in honour of the aviators. The Paulhans, the

Curtisses, the Ferrises, the de Pennendreffs and Clifford

Harmon were the centre of attention and were served at a

magnificent table of plate glass, illuminated from

beneath by cut glass chandeliers lit by electric bulbs.

The table service and flower decorations were part of the

aviation theme, with "a biplane worked in violets

and greenery and a dirigible and a monoplane in red

carnations and greenery".

Wednesday 19 January, "Arizona Day"

On the Tuesday morning the Los Angeles Herald had

published an article headed "Avation and

Booze", which reported how "occupants of the

grandstand at Aviation Park have been surprised and

shocked by the unblushing and vociferous assiduity with

which perambulating bartenders, carrying their stock of

bottles and glassware in baskets, have plied their

vocation In the midst of the gathering of respectable men

and women". This obviously had effect, because the

next day they reported on the first page that "the

promiscuous sale of liquor at Aviation Park has ceased

suddenly". Chief Detective S. L. Browne of the

district attorney's office stated that "The

liquor selling in the grandstand was stopped before I

reached the grounds. But I found three bars running in

the tent at the rear, and everything there was booming. I

closed the bars, and closed them tight".

Flying conditions were perfect for most of the day, with

clear air and almost no wind. Paulhan took his wife for a

ride out westwards to Redondo Beach and Hermosa Beach at

the coast and back. The flight took 33:45.4 and was

estimated at 34.2 kilometres, a world record distance for

a cross-country passenger flight. Later during the day he

took six other passengers for rides, including newspaper

tycoon William Randolph Hearst. During one of the flights

the passenger was Lieutenant Paul Beck of the US Army and

the purpose was to drop dummy bombs on a 25-foot square

target marked on the ground. The attacks were made from

an altitude of 75 metres and were not quite successful,

because the bombs had to be dropped by the pilot. The

best bomb missed the target by 20 meters.

Hamilton made several flights, his best reaching an

altitude of 162 m during a flight of 8:04.4 before he was

topped by engine trouble. He also tried for the endurance

prize, but had to land already after 11:01.2, having

covered 9.7 km. In the one-lap speed contest he was

clocked at 2:47.4.

Lincoln Beachey won a closely contested one-lap

race-horse start dirigible race over Knabenshue and set a

new best time of 4:57.8. Knabenshue's losing time was

5:05.0. After his previous hops Hillery Beachey made the

first real flight in the Gill-Dosh plane. He covered more

than two kilometers at a height of some five metres, but

then the engine quit. In following crash landing the

landing gear and lower wings were once again broken.

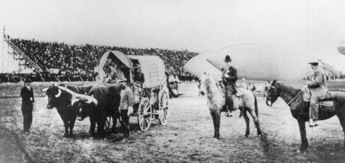

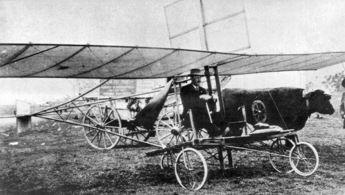

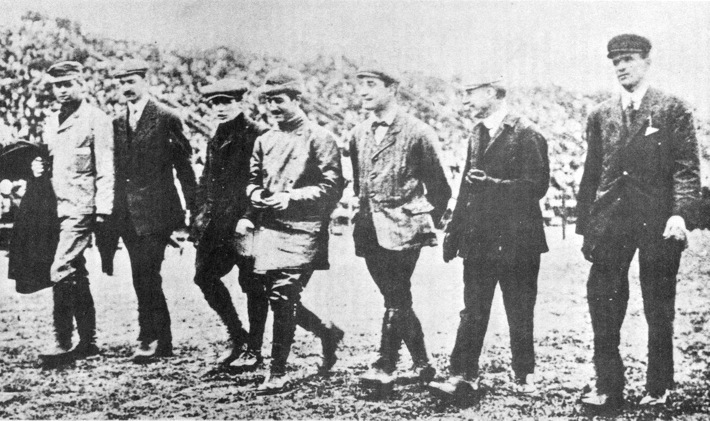

Thursday 20 January 20, "Merchants and

Manufacturers Day"

Before the flying started on the last day there was a

parade that celebrated the aviators and the development

of transportation through the years. It was led by a band

playing the "Marseillaise" in honour of Paulhan

and his team. Next was an old prairie wagon drawn by two

oxen, driven by the legendary pioneer Ezra Meeker,

veteran of the Oregon Trail and promoter of its history.

Then came cowboys on horses and scouts on foot, a mule, a

carriage drawn by two horses, a white goat, a bicycle, a

motorcycle, an automobile carrying Mr. and Mrs. Dick

Ferris, a large spherical balloon, and two dirigibles

being towed by militiamen. Then came the airplanes, first

some of those that didn't fly during the meeting: The

Fowler "Desert Eagle", the Eaton-Twining

monoplane, the Smith "Dragonfly II" and

Professor Zerbe's quintuplane, which had apparently

been repaired. They were followed by the actual flyers,

the three Curtisses of Curtiss himself, Willard and

Hamilton and finally the aviators walking in line. D. A.

Hamburger, chairman of the aviation committee, made a

short speech and presented the flyers and some of the

organizers with medals as souvenirs of the meeting.

By the time the flying started, around two o'clock,

the rain cloud which had threatened during the morning

had mainly dispersed. First out was the dirigibles, but

they were followed at around 3:30 by first Paulhan and

then Curtiss, who were both going for both the ten-lap

speed contest and the endurance contest. The faster

Curtiss lapped Paulhan several times before being forced

down by a broken rib after covering 33 laps of the course

(85.9 km) in 1 h 25:05. Paulhan kept going until forced

down by the curfew, completing 40 laps, a distance of

103.7 km in 1 h 49:40.8. While they were flying, Hamilton

improved his best altitude to 230 m, before going on a 10

km cross-country flight to Gardena and back. On returning

his crankshaft broke, but fortunately very close to the

field, so that he could glide in for a safe landing from

an altitude of 60 meters. Willard and Masson (on a

Farman) also flew during the last day.

Conclusion

With a total of only six pilots completing a lap of the

course the Los Angeles meeting certainly didn't come

close to matching the Reims meeting, but a couple of

world records were broken and it was a great crowd

success. It was also an organizational and financial

success. The meeting had a total of 176,466 visitors and

total income from ticket sales was some 137,000 dollars,

which meant that those who had invested in the meeting

got their money back plus a 25 percent interest. Planning

for a second meeting a year later started

immediately.

Back to the top of

the page

Back to the top of

the page