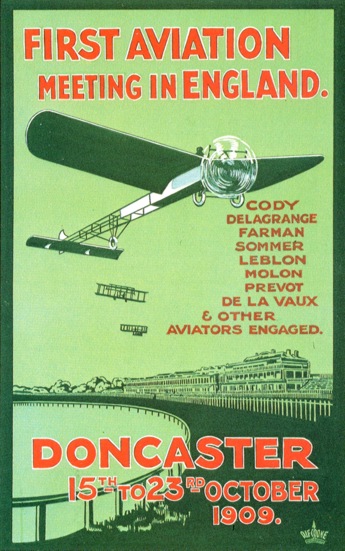

Doncaster, UK, October 15th - 26th 1909

The first air race meeting in Britain

Doncaster is a town in South Yorkshire in northern

England. In 1909 it had a population of around 30,000 and

a healthy industry focussed on railway equipment and

other manufacture. In the middle of September 1909 it was

announced that the town would host an aviation meeting.

The corporation behind the meeting had support from the

Town Council of Doncaster and the owner of the Doncaster

horse racing course, where the meeting was to be held. It

guaranteed £ 5,000 towards the expenses and had

contracted several flyers. Frantz Reichel, the sporting

editor the French newspaper "Le Figaro", would

take care of the general arrangements, just as he had at

the recent meeting in Spa in Belgium.

The announcement immediately caused controversy in

British aviation circles, since the Aero Club of the

United Kingdom (and thereby the FAI) had already

sanctioned a meeting in Blackpool at a clashing date. The

committee of the Aero Club declared at a meeting on

October 6th that they could not sanction the Doncaster

meeting. It was stated that "considering the

scarcity of prominent aviators, it is palpable that such

a proceeding is bound seriously to prejudice the success

of both meetings, and if for no other reason should be

banned". The aviators who persisted in taking part

in the Doncaster meeting would be disqualified from

taking part in any International competitions throughout

the world.

Accusations were soon crossing the air. Some stated that

the decision was an attack on free enterprise and that

Britain was big enough for two simultaneous meetings. The

Blackpool organisers claimed that the Doncaster

organisers were trying to overbid flyers who were already

contacted for Blackpool. The Doncaster organisers claimed

that they had decided the date long ago and that there

was no other possible date, since the grounds were

occupied by horse races. The French flyers who were

contracted to fly at Doncaster stated that they

didn't care about the decision, that they had signed

in good faith and that the FAI had let them down. The

committee of the Aero Club held another meeting on

October 12th, in presence of representatives from

Doncaster, and unanimously concluded that they would not

change their decision. The British aviation press chose

different positions - the Aero Club's organ

"Flight" stuck firmly to the Club's

position, while the independent "The Aero"

reported enthusiastically about the Doncaster meeting and

compared it favourably with the Blackpool meeting.

The Doncaster meeting went ahead despite the

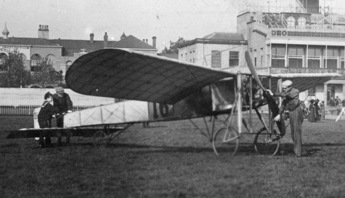

controversies. The following flyers were entered:

- Samuel Cody (Cody)

- Léon Delagrange (Blériot XI)

- Hubert Le Blon (Blériot XI)

- Edward Mines (Mines)

- Léon Molon (Blériot XI)

- Georges Prévoteau* (Blériot XI)

- Georges Saunier (Chauvière)

- Louis Schreck (Wright)

- Roger Sommer (Farman)

- John van der Burch (Blériot)

- Walter Windham (Windham No 3)

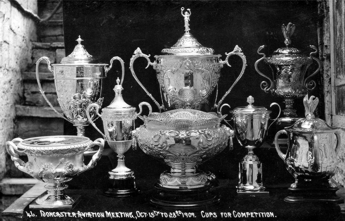

The prizes included the Doncaster Cup for the pilot flying the longest total distance, the Great Northern Railway Cup for the greatest distance flown, the Doncaster Tradesmen Cup for the longest time in the air, the Chairman's Cup for the highest speed over two laps, and other cups for height, passenger-carrying, the best cross-country journey, and the best flight by a British aviator. Cash prizes were also given, but the amounts are only known for some events.

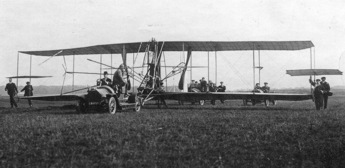

Friday October 15th

The opening day was chosen three days earlier than the opening day of the Blackpool meeting, probably not by coincidence… The rain poured down during the first day of the meeting, accompanied by a strong wind. The crowd "accepted its disappointment with characteristic Northern good humour", even though all they got to see was four machines which had been lined up in front of the grandstands doing some engine runs. One of the four machines was the monoplane of Captain Windham, which suffered a structural failure when it was caught by a gust. The fuselage could not stand the weight of the pilot, so the top longerons collapsed in compression and the fuselage folded. The crowd also got to see Cody drive his plane on the ground across the field in order to test his balky engine.

Saturday October 16th

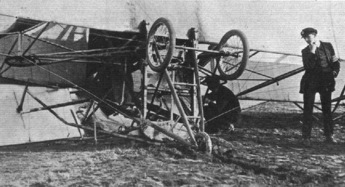

The second day saw much improved weather, with blue skies and a fresh breeze. Le Blon, Cody, Sommer and Delagrange started the flying with some short test hops already during the morning. Cody then made a flight of three quarters of a lap, before landing in order to avoid a pylon. Unfortunately the front wheel hit some soft sand, a "veritable death trap" according to Cody, dug down and put the plane on its nose. Cody was thrown out, but escaped with only a cut forehead. The accident happened on the far end of the field and Delagrange started his Blériot and flew out to see if he could be of assistance. This has been claimed to be the world's first airborne rescue operation. Cody's plane was soon retrieved by car, and repairs were started.

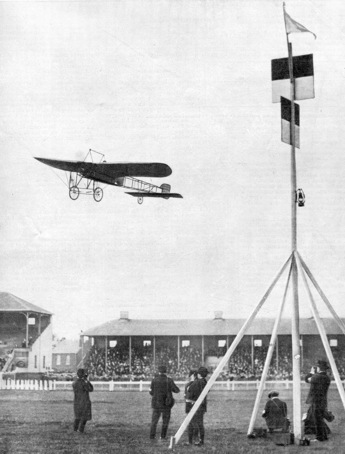

Early in the afternoon the wind increased for a while, making flights impossible, but around three o'clock conditions improved again so that the 70,000 spectators could enjoy continuous flying until dusk. Delagrange again took his plane out and made a flight of five laps (9.2 km) in 11:25.6, which won him the Doncaster Town Cup. Sommer made a couple of flights, the longest 15.6 km in 21:45. Molon, Le Blon and Prévoteau also made good flights in their Blériots, while Schreck crashed his wheel-equipped Wright after a "sensationally unstable" flight of around 100 meters. The plane was seriously damaged and didn't fly any more during the meeting. During the evening Sommer made a flight with a passenger. Delagrange showed his skill in handling the Blériot by starting it single-handed - spinning the propeller himself, ducking under the wing of the moving plane, catching the plane, climbing in and lifting off within forty feet!

Sunday 17 October

Sunday was a free day and the only one to fly was Sommer, who unofficially covered three laps.

Monday October 18th

50,000 spectators again turned out on the third official day of the meeting. In the morning the winds were gusty, so no flying was done. Delagrange made the first flight around noon, but the wind was still close to 8 m/s and he was badly tossed around. During the afternoon eleven more flights were made, the best by Le Blon and Sommer. Le Blon won the Bradford Cup for the fastest ten laps, covering the distance in 20:22.6. He didn't stop after the ten laps, but continued in the by now heavy rain. He had to stop after fifteen laps because of the physical pain of the rain hitting him for ten minutes. Sommer made two failed attempts at the Bradford Cup, but had sparkplug problems and had to come down after four and three laps, respectively. Molon made a good flight, but engine trouble forced him to land close to where Cody had crashed. His landing gear hit a ditch and was badly damaged. Captain Windham had repaired his plane and brought it out for a test, but "certain fundamental constructional principles refused to be transgressed" and to his embarrassment the fuselage collapsed in the same way again when he collided with a stationary automobile while taxying. Towards the evening Sommer tried again to beat Le Blon's time. He flew his ten laps in 25:30.4, half of the time in darkness.

Tuesday October 19th

The main event of the fourth day was the Leeds Cup, for the longest distance covered in 45 minutes. The winds were again gusty, with an average wind speed of around 5 m/s, so no great distances were flown. Le Blon made a couple of flights, the longest covering 22.4 km in 20:37.2. During this flight he was several times blown far off the course, once even flying above the heads of the spectators. He received a tremendous ovation after finishing his "thrilling duel with the elements". Sommer's longest flight lasted five laps (11.2 km), before he was forced to land because the wind was affecting his eyes. After a great effort Cody's plane had been repaired, but his engine refused to run on all eight cylinders, so he only made a two-lap flight, sometimes touching the ground. Delagrange also made a short flight. The Chauvière monoplane arrived during the day, but it didn't yet have its intended 60 hp Clerget engine and was only brought in order to be displayed. It was sold immediately after the meeting.

Wednesday October 20th

The weather was bright and clear, but strong winds stopped all flying during the morning except Cody, who made a couple of short hops in front of the grandstands. In the late afternoon Le Blon and Sommer made some short flights. The fearless Le Blon, who had only made his first flights a month before the Doncaster meeting, was once again tossed around wildly by the winds during a one-lap flight, which his fellow aviators watched in horror. According to the reporter from The Aero it was "probably the most difficult and daring flight that has ever been attempted". Edward Mines brought out his rather unorthodox biplane, but to nobody's surprise he didn't manage to take off. Captain J. G. Lovelace made a couple of test hops in a Blériot that had been bought by William Ballin Hinde. The wind dropped during the late afternoon, and after sunset Sommer flew four laps in the light of the new moon during a flight of 9:45, "a profoundly impressive spectacle".

Thursday October 21st

Strong winds, rain and thunderstorms meant that the 50,000 spectators saw absolutely no flying. The only activity of interest was a ceremony in which Cody was made a British citizen. Ever the showman, he took the oath of allegiance at the airfield before the town clerk of Doncaster and then stood bareheaded while the band played "The Star-Spangled Banner" and "God Save the King". Afterwards he immediately sent in his entry for the Daily Mail £ 1,000 prize for the first British pilot to fly a closed-circuit mile in an all-British machine.

Friday October 22nd

The bad weather continued, and the Town Council of Doncaster decided to extend the meeting by two days as compensation. Sommer challenged Cody on a 10,000 francs side-bet on a five-lap race, but because of his engine problems Cody didn't accept the challenge.

Saturday October 23rd

Despite the continued bad weather and strong winds Lovelace made a flight in Ballin Hinde's Blériot in the morning. After only 200 meters he was driven down by a gust and the heavy landing damaged the propeller and landing gear. The different machines were paraded in front of the crowd of 22,000 in order to give them something to look at, but the wind threatened to destroy the planes even on the ground.

Monday October 25th

After another quiet Sunday the extended meeting resumed. The weather had improved and flying started already at seven o'clock in the morning, before the officials had arrived. First Sommer, then Cody and last Delagrange made short flights, then Sommer took a passenger for a flight. Delagrange tried his new Blériot, which he had equipped with a 50 hp Gnôme engine. He covered five laps in 10:44.4, thereby winning the Nicholson Cup by beating Sommer's 10:50.0. During mid-day nothing much happened. Around 15:30 Cody flew around the course, and then Le Blon took off for what turned out to be a wild ride. After having been blown off course he appeared to have the situation under control, when the plane suddenly touched the ground at full speed and swerved towards the spectators in the "shilling enclosure". A disaster appeared inevitable, but through a combination of luck and skill Le Blon managed to jump first the white racecourse fence and the ditch in front of it and then the crowds, "as though they were a fence in a steeplechase". The slipstream from the propeller blew the hats off several spectators. After this close call the plane crashed to the ground, damaging the propeller and landing gear. His exciting flights earlier during the meeting had already made Le Blon a crowd favourite, and after surviving this spectacular incident unharmed he was carried back to his hangar on the shoulders of worshippers. He afterwards said that he had had no time to think, and he was almost unable to realise exactly what had happened. He just admitted that he had misjudged the wind.

Tuesday October 26th

Most of the last day's flying was done in the morning. Sommer was out first, "wrapped up to the eyes" to protect him from the cold. He won the Chairman's Cup for the fastest five-lap flight by a biplane with a well-polished flight of 12:27.6. It was in fact a walk-over, since Cody had the only other flying biplane, and he didn't make any competitive flights during the meeting. Delagrange was next, and he was going for the speed records in his Gnôme-engined machine. He made steady improvements during three laps and finally reached 1:47.2, before being forced down by the cold. His time equalled 80.3 km/h (49.9 mph). This was claimed as a world speed record, but since the meeting was not sanctioned it could of course not be approved. Then Sommer came out again, going for the Whitworth Cup, for the longest flight of the day, and at the same time increasing his lead in the prize for the greatest distance covered during the meeting. He was in the air for 44:53, covering 20 laps. This was the longest flight of the meeting. After landing he stated that he could have gone on much longer, but that the cold was unbearable. During the afternoon the wind increased again, so this was the end of the meeting.

Conclusion

Only four pilots made significant flights during the meeting, which can hardly have been considered a great success. Altogether an estimated total of 160,000 persons visited the meeting and the total distance flown was around 360 km.

Already before the meeting started there were disagreements between the organizers. On the opening day the Chancery Court appointed an interim receiver to take charge of the takings during the meeting. It appears the local Doncaster corporation, including the Town Council, didn't trust "sports manager" William Caspar, who had travelled to Reims at their expense acting as director of the meeting and via Frantz Reichel contracted the French flyers. There were different allegations about who were actually moving behind the scenes and who had claims to the gate money. In the end, there was no money to share. The corporation had guaranteed £ 5,000 to cover the expenses, but the meeting made a loss of £ 8,000. According to the German magazine "Flugsport" only the appearance money for the flyers amounted to the enormous sum of £ 11,600, of which £ 6,000 for Delagrange and his team (Le Blon, Molon and Prévoteau).

The aftermath

In the beginning of November the Committee of the Aero Club, as obliged by the FAI, suspended Delagrange, Sommer, Le Blon, and Molon from taking part in any contests held under FAI rules until January 1st, 1910. Cody, who assured that he had not taken part in any competitive events at Doncaster, managed to get away without punishment.

On November 19th the Aéro-Club de France sent a letter to the President of the Aero Club. While accepting the judgement of the Aero Club, they appealed that the disqualifications for Delagrange, Le Blon and Molon should be shortened by a month, so that they would be able to compete for the 1909 Michelin Cup, which ended on December 31st. They pleaded as extenuating circumstances that the flyers had signed contracts with the Doncaster organizers already in August, two months before it was known that the Doncaster meeting wouldn't be sanctioned. The flyers would have risked having to pay damages for breach of these contracts if they hadn't turned up.

After hearing these arguments, the Aero Club remitted one month of the disqualifications, but the committee still felt that "it would be desirable that these three aviators should fully recognize the justice of the sentence pronounced upon them, and to that end would be glad to receive from these three gentlemen a letter acknowledging this fact". At least Molon wrote such an apologetic letter, which was duly published in "Flight". Sommer had sold his plane for £ 1,200 after the end of the Doncaster meeting, and was about to start building planes of his own design, so he probably cared little about the disqualification.

These controversies, and the feeling that aviation in the United Kingdom was being run by a centralist London group, led to the formation a breakaway organization of local aviation societies, the "Aeroplane Club of Great Britain and Ireland", but it appears that it didn't last very long.

(1)

Back to the top of the page

Back to the top of the page