Bournemouth, UK, July 11th - 16th, 1910

The first 1910 British international aviation meeting

Bournemouth is a coastal resort town in Dorset (until

1974 in Hampshire), on the south coast of England. It was

founded in 1810 by Lewis Tregonwell, who built the first

house in what was then a deserted heathland, occasionally

visited by fishermen and smugglers. It quickly grew to

become a well-known spa and became a town in 1870. The

population had gone from zero to around 75,000 by 1910.

The centennial of the town's existence was celebrated

by what was announced as "The grandest series of

Fêtes ever organised in Great Britain" on July 6th -

16th. One of the main attractions was an international

aviation meeting, but there was also a "flower

battle", carnivals, concerts, a military tattoo, an

athletic meeting, a motorboat regatta, masquerade balls

and many other events.

The meeting was sanctioned by the Royal Aero Club, and

the organisation committee was headed by Councillor F. J.

Bell, the chairman of the Fetes Committee, and W. Bowman,

the organising manager. Four different potential sites

were investigated during the winter, and it was finally

decided on a field between Southbourne and Hengistbury

Head, some six kilometres east of central Bournemouth.

The committee paid the land-owners £ 2,200 for the use of

the grounds. A four-pylon course with two almost hairpin

turns at the ends was laid out. Construction of the

airfield with its four covered grandstands and fifteen

hangars went smoothly and communication via two different

tram lines was assured. The total cost of arranging the

meeting was given as £ 22,000.

In March, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu appealed for

subscriptions to a national prize fund to provide prizes

for British aviators at the meeting. The results were

disappointing and in the end only £ 100 could be given

for the best flight in an all-British machine.

Nineteen competitors entered, all of them licensed

pilots, according to "The Aero" in order to

avoid "the ludicrous scenes which occurred at

Blackpool and Doncaster, when men who never had flown,

and never will fly, came out and played on the grass till

their badly-built machines broke themselves".

Fifteen of the pilots were British or Britain-based,

headed by Charles Rolls, Bertram Dickson, Samuel Cody and

Claude Grahame-White. Four were experienced foreign

pilots: Frenchmen Léon Morane and Louis Wagner, Belgian

Joseph Christiaens and Swiss Edmond Audemars.

The meeting would include the usual contests, with the

highest prize money, £ 1,000, going to the winners of the

speed and altitude contests. £ 800 would be paid to the

winner of an over-water race from the airfield to the

Needles lighthouse at the western end of Isle of Wight

and back. The total prize fund was £ 8,000. There would

be no appearance money paid, so the pilots would have to

compete for their share of the prize money.

One slightly controversial aspect of the meeting was that

the official flying hours of the meeting were from 11:00

to sunset, but no competitor could start in any event

after 19:00. This would to large extent deprive the

flyers of the best flying conditions, which was normally

between 19:00 and 21:00, when the wind usually had

dropped. The clerks of the course could prolong these

hours for special competitions, but for the results all

flights were in general to be officially terminated at

the hour of sunset. The reason given for this rule was

that the flying should not interfere with any of the

other arrangements of the festivities.

The flyers and their machines started arriving during the

week before the meeting, but there was no flying until

the day before the official opening. The Blériot that was

to be flown during the meeting by Armstrong Drexel was

flown into the airfield from its home base, the Beaulieu

Aerodrome in East Boldre, some 30 kilometres away, by

William McArdle, who ran the aerodrome together with

Drexel. This was a daring flight, during which McArdle

avoided flying over the New Forest and instead tried to

follow the coastline. He lost his way in the morning

mist, but finally recognised the Needles and could find

his way to the airfield. During the evening some of the

flyers made test flights. Dickson made a couple of

successful flights, one with a passenger. Christiaens,

James Radley and Grahame-White also made tests, and later

on Launcelot Gibbs tried, but didn't get far before

his propeller disintegrated, the pieces knocking holes in

the wing fabric. Gibbs and George Cockburn had to spend

the night in Gibbs' car, fetching a new propeller

from Cockburn's hangar in Larkhill, a roundtrip of

more than 120 kilometres.

Monday 11 July

The flyers, most of them staying at the Burlington Hotel

in Boscombe, between Bournemouth and the airfield, had

arranged that the first one to wake up after 04:30 would

wake all the others, so that they could make some tests

before the official flights started. One of those who did

was Cecil Grace, who took off at six o'clock to test

his engine after a cracked cylinder head had been

replaced. The repaired engine seized already during the

first lap and he had to land across a road that crossed

the airfield. The sunken road surface had been filled,

but only with loose sand. The wheels got stuck and the

machine was completely wrecked. According to "The

Aero" the uninjured pilot took the setback

"most philosophically" and he hoped to be able

to get a replacement machine already during the day.

During the morning Gibbs came out for a test with his new

propeller, but the engine didn't pull well, perhaps

because the propeller had too course pitch. Alec Ogilvie

also suffered from engine trouble and accepted an offer

from Cecil Grace to use one of his Bollée-Wright engines.

Ogilvie's assistant Searight started at noon for a

drive to Sheppey and back to fetch it, a round-trip of

some 500 kilometres, with the prospect of afterwards

having to work all night to fit it. Rolls made a test

flight of four laps in the morning. Grahame-White also

made a test, and then took up a passenger for a short

flight.

The weather was perfect at eleven o'clock when

official flights started: No wind and a covered sky.

Already after five minutes Christiaens was in the air,

starting a series of laps. Around forty minutes later

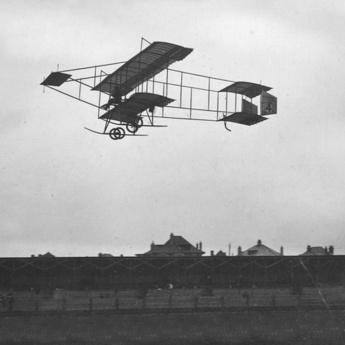

Rolls took off. Apart from the test in the morning, this

was the first flight since the tail of his Wright had

been modified. The fixed horizontal rear stabilizer that

he had used since the Nice meeting in April had been

replaced with an all-movable elevator, which was coupled

to the front elevator. This design, which was similar to

the one used on the 1910-style Farmans, had been designed

by Count Charles de Lambert and built by the Wright

factory in France. Rolls climbed to an official 296

metres before spiralling down to land after a flight of

around 30 minutes. Before the landing he made an effort

for the slowest lap contest, throttling down the engine

and majestically cruising around the course with the nose

high. His lap took 4:13, which corresponds to an average

speed of about 41 km/h. During Rolls' flight James

Radley made a fast three-lap flight in his Blériot. When

Radley had landed, Grahame-White made a short flight to

familiarize himself with the course, making elegantly

banked turns close to the pylons in contrast to

Christiaens' wider and flatter turns.

Only a few minutes after landing Rolls took off again and

flew five laps for the speed contest. Armstrong Drexel

took off in his new Gnôme-engined Blériot and immediately

climbed to an impressive altitude. He was not sure that

it was officially measured, since he had run into wet

mist and couldn't see the line on the ground that

marked the measuring point, but according to the official

results he had reached 595 metres. While Drexel was in

the air Dickson took off, like Grahame-White not going

for any prizes but only for practice around the course.

Around half past one Christiaens finally landed after a

flight of 47 laps in 2 h 20:52.2, which would turn out to

be the second longest flight of the meeting. The inlet

valves of his Gnôme engine had started to stick, so the

engine lost power. Then the airfield turned quiet for a

couple of hours, while most pilots and crews took a lunch

break.

During the break George Barnes took off in his Humber,

but after a short flight he landed in tall grass and put

the machine on its nose. He was not injured, but the

damaged machine would keep him out of action for two

days. Alan Boyle also tried a couple of times, but he had

to abort the first flight because the wings were badly

adjusted and then the engine of his Avis monoplane

refused to cooperate.

Soon after four the afternoon's flying started.

Grahame-White took off for the altitude prize and reached

506 metres. Radley flew a lap for the speed prize. Around

five o'clock Rolls also tried for the altitude prize,

but gave up at around 300 metres because he felt that the

machine behaved strangely and didn't react correctly

to the controls. Whatever the problem was, probably some

turbulence, it seems it solved itself. The machine soon

felt normal again and nothing could be found afterwards.

Around this time somebody found a gap in the fence on the

northern end of the airfield. Hundreds of people from the

spectator area entered the airfield and disturbed the

traffic in the hangar area. Some mounted policemen were

called into action and soon cleared them out and sent

them back to their enclosure.

When order had been re-established Rolls took off for the

five-lap speed contest, trying to beat Grahame-White, who

had the best time so far. He succeeded, posting a time of

14:39.4. He was followed by Gibbs, Radley and Boyle, who

all tried less successfully for the speed contests.

Around a quarter past six Grahame-White filled his tanks

and took of for the longest-flight prize. The clouds had

disappeared during the afternoon and when Drexel made his

second try for the altitude prize he had no problems. He

reached 759 metres and won the daily altitude prize, the

first prize of the meeting to be won. Radley, on his

third try, and then Christiaens both managed to beat

Rolls' speeds, the day's best time over five laps

being Christiaens' 13:32.2.

Soon afterwards Dickson took off, flew a couple of laps

around the course and finished with a perfect "vol

plané". He then took off again and climbed to some

350 metres before aiming his machine westwards and

disappearing towards the Bournemouth city centre. He was

gone for a quarter of an hour before he was spotted

returning over Southbourne, obviously coming down from

high altitude. He flew two laps around the course, then

cut the engine at the far end of the airfield and glided

across the entire field in a straight vol plané. He

briefly started the engine in order to clear a rough

patch, then cut it again for a perfect landing right in

front of the hangars. According to "The Aero"

it was "the most beautiful piece of judgment of

distance and pace one could possibly see, and moved the

privileged few in the envied hangar enclosure to such a

pitch of enthusiasm that they rushed out to the machine

and practically carried Dickson back in triumph".

While this was going on Grahame-White was still circling,

and he didn't land until 20:50, after a flight of 52

laps in 2 h 34:56.2 that would eventually win him the

longest flight prize. The timing should have stopped at

sunset, which was at 20:13, but the officials had wavered

the curfew rule and let the clocks run, a decision that

would prove controversial.

Tuesday 12 July

The airfield was quiet during the morning. The first

event of the day was the first day of the precision

landing contest, which was to be held between 11:00 and

13:00. Although the weather was bright, the contest was

troubled by winds of up to 6 m/s that blew from the

southeast along the airfield, obliquely across the course

and towards the grandstands. The target for the contest

was the centre of a circle with a diameter of 100 yards

that was marked across the start/finish line in front of

the grandstand, and before the landing the flyers had to

cross the start/finish line.

Grahame-White was first to try. He chose to turn left

after the first pylon and then fly a low S-turn across

the wind and land with the wind from behind and right. He

had some trouble stopping his engine and therefore

overshot the target by 13 metres. Audemars was second to

try. His machine had arrived during the night and this

was his first flight. After a very quick take-off he flew

a lap around the course, but then came down in high

grass. The light-tailed Demoiselle nosed over and came to

rest flat on its back. Neither the pilot nor the machine

was damaged, and he would be back in the air after a

couple of hours. Then Rolls made his first effort, trying

the same lines as Grahame-White and overshooting by 24

metres. Next came Dickson. He landed downwind, cut his

engine outside the circle and tried to slow the machine

down by pulling his elevator sharp up. He lost lift and

dropped almost vertically from several metres. He landed

very heavily and broke the landing gear and a wing, and a

rigging wire from the landing gear got tangled in the

propeller and the valve mechanism of the still rotating

engine.

Just before one o'clock Rolls made a second attempt.

This time he tried a different line, circling back to fly

far outside the course and approach the circle straight

into the wind from above the grandstands. He descended

steeply after clearing the grandstands and crossed the

airfield fence around 40 feet above the ground. It was

obvious that he was about to undershoot, so he pulled the

elevator sharply. The sudden control input overloaded the

lightly built structure that held the rear elevator,

which collapsed with a sharp crack. Deprived of the

control surface, the machine pitched down and hit the

ground almost vertically. It rolled over on its back and

Rolls was thrown out of his seat and came to rest on the

inverted top wing. The accident had happened just in

front of the main grandstands and lots of people came

running. Policemen and officials formed a ring around the

accident site to stop photographers and curious

spectators from reaching the machine.

From a distance Rolls didn't look badly injured, but

he had died immediately from the violent concussion. He

was the first British pilot to die in an air accident,

and the ninth in the world. He was not only one of the

most proficient British flyers, but also a scientifically

interested person, and his death was a heavy loss for

British aviation. In the aftermath of the accident it was

questioned whether the landing contest should have been

postponed in view of the difficult wind conditions. The

most likely cause of the failure of the tail was found to

be that one of the light struts that formed the outrigger

structure had buckled sideways due to the sudden vertical

load on the elevator and been struck by one of the

propellers.

The rest of the day's program was immediately

cancelled in respect of the tragedy.

Wednesday 13 July

The weather was bright, but still too windy to be a

perfect flying day. In the morning Cody tested his

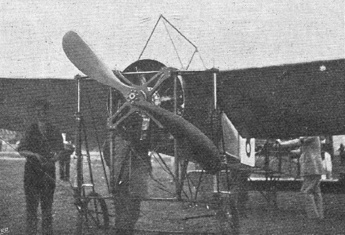

machine, but the engine didn't run well. His new

machine had originally been intended for a 100 hp Phoenix

rotary engine, but this could not be delivered and the

backup plan was to use two 50-60 hp Green engines. Only

one of these were fitted, and it was obviously not

enough. Ogilvie tested his Wright, now fitted with

Grace's engine, and completed four laps of the course

before making a neat practice landing at the target of

the landing contest, coming down within four metres of

the centre.

The organisers were careful not to risk another serious

accident and therefore decided to postpone the

weight-carrying contest that should have been run on the

Wednesday and Thursday. They thought, quite correctly as

developments would prove, that it invited risky flying.

After the opening of official flights at eleven

o'clock Grahame-White was first in the air, at 11:15.

He first made a short test flight and then a longer

flight with a passenger. An hour later Cody made another

unsatisfactory test and returned to his hangar. Not much

happened until Morane flew two fast laps in his brand new

"racing" single-seat machine at half past one.

After he landed Grahame-White made another passenger

flight. Around three o'clock Dickson flew a couple of

laps, and then Grahame-White made a series of passenger

flights.

At around four o'clock the patient crowd finally got

some "much-needed comic relief", according to

the reporter from "The Aero", when Audemars

turned out with his Demoiselle. He continued:

"Nothing so excruciatingly funny as the action of

this machine has ever been seen at any aviation ground.

The little two-cylinder engine pops away with a sound

like the frantic drawing of ginger-beer corks; the

machine scutters along the ground with its tail well up;

then down comes the tail suddenly and seems to slap the

ground while the front jumps up, and all the spectators

rock with laughter. The whole attitude and the jerky

action of the machine suggest a grasshopper in a furious

rage, and the impression is intensified when it comes

down, as it did twice on Wednesday, in the long grass,

burying its head in the ground in its temper".

Audemars explained that he was quite used to the machine

nosing over, and that it seldom caused any damages. He

wore a padded leather helmet and when he came down to

land he prepared himself by bracing himself with the head

against the fuselage tubing and his feet on the pedals.

According to the reporter, Audemars had a stack of spare

wings in his hangar, "like a pack of cards",

and the fixed central part of the wing was "like a

patchwork quilt where it has had bits of fabric stuck on

after turning over on rough ground and having holes

knocked in it".

At five o'clock Morane brought out his Blériot again

and made a spectacular vol plané in a tight spiral from a

height of around 100 metres. At around six o'clock he

made a third flight, this time climbing high at a steep

angle in small circles, hardly leaving the airfield.

After climbing for nine minutes he again switched off the

engine and spiralled down. After a turn around the

timers' pavilion, he landed in the middle of the

landing target circle, bounced off it, switched on the

engine, flew another circle and then back to his hangar.

His altitude was recorded as 1,252 metres, winning the

day's altitude prize and beating Drexel's mark

from the day before.

As usual the action improved towards the evening when the

wind decreased, and the flying went on until nine

o'clock on a perfect evening. Grahame-White made

several more passenger flights in his

"aerobus". Grace, Barnes and Boyle all made

short flights, all suffering from engine troubles, the

latter landing in the bracken outside the course. Drexel

tried to take back his lead in the altitude contest, but

his engine didn't deliver full power and he had to

give up. Morane flew five fast laps for the speed prize.

His time was 9:34.4, a result that wouldn't be beaten

during the rest of the meeting. His best lap time was

1:53.4, which would also stand unbeaten. Wagner's

crew had assembled his Hanriot during the day and he made

a test flight, the stability of the machine in the air

impressing the onlookers. Rawlinson made a short flight.

Dickson took Morane as a passenger in his Farman,

reportedly with Morane working the stick and Dickson the

pedals. Gibbs tried to fly a lap with a lady passenger,

but his engine was still not pulling well and to add to

his misery the machine was difficult to control and

didn't want to leave the ground. Ogilvie made a

second flight and landed at the far end of the field. One

of the cylinders of his borrowed engine had blown off,

which meant another long drive for Mr. Searight to fetch

a new replacement, this time a 350-kilometre roundtrip to

London! The last to land was Audemars, who despite his

two somersaults flew several laps during the day and

finished with his best time of the day, 2:24.4.

Thursday 14 July

At six o'clock on the morning Cody made a test flight

of almost a lap. The official flying of the day started

with the second and last day of the contests for starting

and landing prize, which were scheduled to take place

between eleven o'clock and one o'clock. Most

pilots didn't try during the first hour and a half,

so things got quite rushed and confused at the end, and

nobody even got to make the second of their three allowed

efforts. Ogilvie, who had fitted wheels to his

Short/Wright, which normally started from a rail, in

order to be allowed to participate in the event ran out

of time completely in the queue for the landing contest

and couldn't even make a single effort.

The two contests took place at the same time, and the

pilots could try for both prizes during the same flight.

Only Grahame-White, Christiaens, and Dickson tried this,

since it necessitated a 360-degree turn and even though

the wind was blowing from a favourable direction most

pilots thought it was not worth the risk. Eight pilots

contested the starting prize. Dickson won by taking off

in 32.18 meters, beating Morane by the unbelievably

narrow margin of one inch. How anybody could have judged

this by eyesight is beyond belief…

Just after one o'clock Grahame-White made a second

effort, which was good enough to have moved him into

first place. Christiaens, supported by Morane, Audemars

and Wagner, protested strongly when Grahame-White's

result was initially allowed. They thought that decision,

together with the decision to allow Grahame-White to be

timed after sunset on the first day, a possibility that

the claimed they weren't even informed about, proved

that the British flyers were favoured by the officials.

They shut their doors, hauled down the flags from their

hangars and threatened to go on strike and leave the

airfield. Some of the British flyers sportingly sided

with them. The officials made a quick investigation and

found out that the watch of one of them was four minutes

behind, so Grahame-White's second effort was

disallowed. This pleased the foreign pilots, who hoisted

their flags again.

All the three pilots who tried to improve their landing

prize results succeeded. Grahame-White landed seven feet

of the centre of the target and won. Christiaens got

within nine metres and took second, while the unfortunate

Rolls' best effort from the Tuesday remained good

enough for third. After the rush to finish these contests

the wind from the sea increased and brought mist and

lower temperatures with it.

It was not until around six o'clock that action

started again. Grahame-White made several passenger

flights all through the evening. On one of them he

brought a photographer with a cinema camera who took

movie pictures over the sea and the airfield

installations. The well-known actor Robert Loraine, who

flew under the pseudonym "Jones", brought out

his Farman for the first time. His crew had worked around

the clock for three days, repairing it after a crash the

week before. The test went well, but after a couple of

laps he landed at the far end of the field. Dickson made

a couple of flights, again finishing with a long glide

from the far end of the field. Radley flew a couple of

laps, showing good speed. Morane made two flights,

reaching 625 metres during the second. Grace flew a lap

for the speed contest, but he landed on the straight

after the start/finish line.

The crowd-pleasing Audemars kept the crowds amused with

some tricks: He could make pirouettes on one wheel, and

he could make the machine bow to the applause of the

spectators by lifting the tail! He flew five laps in

11:56.8, putting him in second place in the speed

contest. His one-lap time of 2:20.8, also good enough for

second after Morane, who didn't improve on his

previous best times, despite turning extremely tight and

banking steeply. Wagner also tried for the speed contest.

His corresponding results were 12:18.8 and 2:24.2, good

enough for third place. Both Dickson and Grahame-White

made two efforts at the slow flying price, but they

couldn't beat Rolls' time from the first day.

Later in the evening both Loraine and Grace managed to

bring their machines back to their hangars under their

own power. Radley and Boyle took off. The former had to

give up early with a seized engine, but Boyle made a

successful flight. While Boyle was in the air Rawlinson

took off in his Farman, an old and worn machine that

always flew with the left wing low. On the back straight

he dropped too low and the left wing touched the soft

ground. The machine slewed sideways and crashed to the

ground. The landing gear was wiped out, together with the

rudder pedals and footrests, which were below the level

of the leading edge of the lower wing. Rawlinson broke

his left ankle immediately in the crash, and when he hit

the ground after being thrown off the seat he dislocated

his right shoulder. According to the reporter from

"The Aero" the plucky Rawlinson, conscious all

the time and in obvious great pain, chatted amicably with

the stretcher bearers when he was carried away.

Friday 15 July

The weather was fine in the morning, but during the day

the winds from the south-east increased and in the end

stopped all flying. No competitive flying took place

until three o'clock, when the postponed

weight-carrying contest started. The object of this

contest was to carry the heaviest payload, including at

least one passenger, around one lap of the course. Morane

was first to take off, but his flight with M. Chereau,

Blériot's British manager, as passenger was only a

short test of the new two-seat model XI-2 bis, which

suffered from problems with the wing warping controls.

The first competitive flight was made by Grahame-White,

who in addition to Fred Coleman of the White Steam Car

company also took some lead sheet aboard to increase the

payload. They didn't get further than the first pylon

since the engine didn't run well.

Next off was Christiaens, with his mechanic Mr. Mathis as

passenger. They got off well and completed the first

straight in the 7 m/s headwind and passed the second

pylon. They were flying low, and when they turned across

the wind around the sharp turn at the third pylon they

didn't carry enough speed. When they got the wind

from behind they quickly lost the little altitude that

they had. Christiaens tried to turn out of the tailwind,

but they came down in a barley field outside the course.

Christiaens tried to take off immediately while still

rolling, with the only result that the machine hit the

ditch at the end of the field. With the wheels stuck in

the ditch the machine turned over into the neighbouring

field, throwing Christiaens and his passenger off. They

were lucky, because the fuselage turned over completely,

the engine tearing itself loose and crushing everything

in front of it. Christiaens initially only complained

about a strained back, but he had to withdraw from the

Brussels meeting a week afterwards, not only because his

machine was destroyed, but also because of an unhealed

leg wound and kidney pains. Mathis only suffered a

bruised shoulder. The machine was completely destroyed

and the tail broke off and fell back into the first

field. Christiaens was driven to his hotel, where he had

to rest for a couple of days, but Mathis stayed at the

wreck, working with one hand to remove the few parts that

were worth salvaging.

Dickson was next. After hearing about Christiaens'

accident, he decided immediately before the start to

lighten his machine by 13 kg by changing to a lighter

passenger, the Earl of Hardwicke. The take-off went well

and when approaching the difficult turn at the east end

of the field Dickson showed his airmanship by avoiding

the dangers of the tight turn around the third pylon. He

went wide of the course and used the updraught set up by

the cliffs by the seafront to gain some height. He

didn't lose any altitude at the turn and returned to

make a perfect landing after completing the required lap.

Since he was only competitor to complete the course he

won the prize.

There were again some protests, since the officials had

decided to restrict the contest, which was originally

intended to be run on the two previous days, to only one

day. Furthermore they had decided that all flights had to

be made by 15:30. This ruled out both Morane and

Grahame-White, who both had to make some adjustments and

ran out of time.

Around four o'clock Wagner took off to try to improve

his result in the speed contest. He completed the

required five laps but didn't improve his result. The

Friday was the first day to compete for the Sea Flight

Prize, and the first to try was Morane, who took off at

16:25. He immediately climbed high and disappeared in the

mist. Around 20 minutes later he was spotted from

Hengistbury Head coming back from the Needles in a vol

plané. Spectators in one of the many boats that patrolled

the course stated that he had shut down the engine at

least three kilometres away from land and glided home

with the help of the tailwind. He landed at 16:51 after a

flight of 25:12.4, and his barograph indicated that he

had reached an altitude of 1,200 metres during the

flight.

Drexel took off at 16:35, flying into the by now much

stronger wind. His machine was visibly slower than

Morane's and didn't appear to run well. Around

five o'clock people at the airfield started to worry

that he might have had an accident, but soon afterward he

was spotted over the sea, far south of the direct course

back from the Needles. He finally he landed at 17:10, his

engine sounding very sick. He stated that it had missed

on one cylinder all the way, and that he was quite lost

on the way home, since the sun shining through the haze

over the sea made a white wall in front of him. He had

experienced a lot of turbulence over the Needles. The

updraught set up by the hills on the Isle of Wight

reached him even at a height of 600 metres.

Wagner tried next, but his landing gear was bent during

the bumpy take-off run. He made some temporary repairs

out on the field and could roll back to the hangars under

his own power. Grace tested his engine, which apparently

ran well, because he immediately climbed high and made

two excursions out of the field along the valley of the

river Stour. He was watched by his parents, who had never

seen him fly before. He gave up after reaching 350 metres

because of the turbulence and the strong winds. He came

down with a fine glide, then started the engine near the

ground and flew over the grandstands and public areas. He

finally landed in some soft ground and punctured a tyre,

but his flight was praised because he had managed the

obviously difficult conditions. The wind kept increasing

and the last flights were made by Morane, who impressed

with some dives and steeply banked turns, and

Grahame-White, who made a couple of more passenger

flights in his "aero-taxi".

Saturday 16 July

The morning of the last day of the meeting started with

hard winds from the east, and just after lunch a

rainstorm fell. Not only did it drench all the people

that were on the way to the airfield, it also spoiled the

garden party that F. J. Bell, the chairman of the Fetes

Committee, was giving in honour of the aviators.

Grahame-White's new 100 horsepower Blériot, which had

been delayed on the railway, finally arrived during the

morning. It was intended that Morane would take it up for

its first test flight, since Grahame-White didn't

have any recent experience on monoplanes, but it

didn't make any flights during the meeting.

Farman's engineer Blondeau came down to check

Gibbs' machine and found out that it had been

delivered with the wrong rigging and was completely out

of trim, explaining its poor performance.

The wind speed was around 6 m/s, with gusts up to 11 m/s,

when Loraine made the first flight. He stayed in the air

for 16 minutes, with a best lap of 3:13.4. Then Dickson

started, intending to go for the distance prize, but he

gave up after two laps because of the winds. Audemars

also flew a lap.

Around three o'clock Loraine took off to go for the

sea flight prize. The weather didn't look promising.

The winds had reduced somewhat, but heavy rain clouds

threatened from the east. Loraine was cheered when he

flew the obligatory lap of the course and then steered

out over the sea, where he soon disappeared out of sight

in the mist. Five minutes later a heavy rainstorm struck

the airfield and when Loraine didn't come back after

the expected half hour everybody at the airfield started

to get worried. Time passed - forty-five minutes, then an

hour, then an hour and a quarter and still no news.

People with sailing experience stated that in such

conditions it would be impossible to find somebody who

had fallen into the sea.

Boyle had finally managed to solve the engine problems

that had plagued him the whole week. While Loraine was

still gone he prepared for a flight, despite the rain. He

made a good take-off and rounded the first two pylons,

but then came down in a clover field. The wheels stuck in

the wet vegetation and the machined turned over abruptly.

Boyle was thrown out and hit his head hard against the

steel wing rigging structure in front of the cockpit. He

was fortunately wearing a new felt-padded leather helmet

that he had been given by Morane, and this certainly

saved his life. He didn't break any bones, but he

suffered a very bad concussion and remained unconscious

for more than an hour. He remained in the nearby Boscombe

hospital for more than a month, from time to time

unconscious, before being moved to a local nursing home.

He couldn't leave Bournemouth and go home to his

native Scotland until the end of September. He reportedly

never recovered completely from the effects of the

concussion and still suffered from problems with his

eyesight several months afterwards.

Wagner flew five laps for the speed contest. His time was

reported as 9:57, with a fastest lap of 1:57. This was a

big improvement on his previous best and would have been

good enough for second place, but for some reason it was

not recorded in the list of results. He landed heavily

after completing the flight and broke the landing gear.

Radley flew a lap and then Morane took "Géo"

Chávez, who had recently bought a Blériot, on board for a

passenger flight. Grace also flew five laps in 12:12,

also an improvement on his previous best, but like

Wagner's time it was not recorded. Audemars and

Drexel also flew, making it five machines in the air at

the same time. William McArdle, who was not entered as a

competitor, borrowed Drexel's machine and made a

flight over Bournemouth to Poole Harbour in the rain,

some fifteen kilometres away, and back. The committee

offered him £ 50 as reward for his fine flight, even

though he was not entered as a competitor. He gracefully

declined it and expressed a wish that it should go to the

Centenary Fetes Fund instead.

At around half past four a telegram finally arrived from

the Needles lighthouse, telling that a biplane had been

seen on the cliffs of the Isle of Wight. This was a big

relief for Loraine's anxious friends at the airfield,

and soon afterwards Loraine himself made a telephone call

and told that he had landed safely near Alum Bay, wet and

cold but completely unharmed. The weather improved

towards the evening and several pilots made flights.

George Colmore, who had spent most of the meeting in his

hangar, finally took out his Short for a first flight.

Since he was the only pilot flying an all-British machine

his only flight won him the £ 100 prize collected by Lord

Montagu. Grace, Dickson and Radley also flew. Audemars

made yet another somersault in his Demoiselle, again

without injuries, but this time necessitating some

repairs. Grahame-White made his trip to the Needles and

back in much better conditions than Loraine. He flew at

high altitude all the way and won the third prize with a

time of 45:47.

The officials had apparently listened to the protests,

because they reopened the weight-carrying contest and

allowed the flyers to try for the second and third

prizes, which hadn't been won the day before.

Grahame-White lifted 193 kilograms and Morane 187, both

results better than Dickson's winning effort of the

day before. Later on, Morane took up two ladies as

passengers at the same time. This was the first time in

Britain when three people flew in a heavier-than-air

machine.

Conclusion

The death of the popular Charles Rolls and the serious

injuries of Alan Boyle and Alfred Rawlinson were hard

blows to British aviation and of course cast a shadow

over the meeting.

Morane won almost half the prize money, and he was also

given the "General Merit Prize", which was

awarded to the competitors who, in the opinion of the

stewards of the meeting, "performed most

meritoriously" during the meeting. Drexel,

Grahame-White and Dickson won second to fourth prizes.

The British aviation press was disappointed with the

performance of the British machines, and particularly the

British engines. It was pointed out that Gnôme-engined

machines won £ 6,915 and machines powered by other French

engines won £ 785, while British engines only accounted

for £ 150, of which £ 100 was a prize that could only be

won by an all-British machine.

The meeting was also criticized for the lack of flying

action during large parts of the days. Most of the

flights were made as late as possible, towards sunset

when conditions were best. Proposals were made for a

prize structure that would encourage flights to be made

all through the day at future meetings.

Back to the top of

the page

Back to the top of

the page