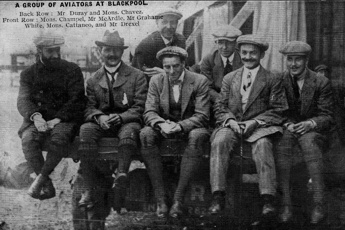

Blackpool, UK, July 28th - August 20th, 1910

Wind and rain, and huge losses...

Despite the disappointing and costly 1909 Blackpool

aviation meeting, the Lancashire Aero Club applied for

sanctions for two national aviation meetings in 1910.

Both were granted by the Royal Aero Club. In June, it was

announced that the two meetings would be merged into a

single event, the Blackpool Flying Carnival, to be held

during a period of three and a half weeks. This unique

schedule included a first competitive part from July 28th

to August 3rd, followed by eleven days of exhibition

flights and static exhibitions, and closing with another

six days of competitive flights from August 15th to

August 20th. It was made even more unique by the

sanctioning of a coinciding British aviation meeting, the

bigger international meeting in Lanark in Scotland, which

was held between August 6th and August 13th. It was

hoped, largely in vain as it turned out, that many of the

participants of the Lanark meeting would participate in

the second half of the Blackpool meeting.

The expenses for the meeting were guaranteed by Mr.

Huntley Walker, the chairman of the Lancashire Aero Club.

The meeting was to be held at Squires Gate, south of

Blackpool, the same site as the 1909 meeting. The

intention was to develop it into a permanent airfield,

with permanent hangars and grandstands. The layout of the

airfield was completely changed in comparison with 1909.

The length of the course was reduced to one mile (1,609

m), requiring only half the area, and the hangars and

grandstands were rearranged.

The first week

The program for the first week consisted of daily prizes for endurance, altitude and "general merit", with an additional prize for the most meritorious performance during the week. In addition, there were several special prizes, some donated by sponsors. Eleven pilots entered, but all of them didn't turn up for the first week.The preparations for the meeting did not work out well. The construction of the hangars and grandstands was delayed by heavy rains, and when the meeting opened only one hangar was ready. There were allegations that parts of the Blackpool establishment didn't really want the meeting to be a success. They had supported the 1909 meeting, which was held in October, since it was hoped that it would attract visitors to the area during an otherwise unattractive part of the year, but now it was speculated that they feared that it would attract visitors to the airfield, who would otherwise have spent their money on the restaurants, bars, theatres and other attractions downtown.

The construction works were not the only problem. The two triplanes that Alliott Verdon Roe had entered were destroyed by fire on the railway at Coppull, near Wigan, during the transport to the meeting. The cars holding Florentin Champel's Voisin and Bartolomeo Cattaneo's Blériot were lost on the railway, and when they were found, the flyers decided to go straight to Lanark instead of participating in the last couple of days of the first Blackpool week.

Thursday 28 July

The shortage of hangars during the first day was matched by a shortage of planes. When the meeting started, only three planes had arrived, two Blériots owned by Claude Grahame-White and one owned by Cecil Grace, and none of them was ready to fly. Around 5,000 people had paid for entrance, encouraged by the weather improving after some morning showers. After waiting until half past five they had had enough and stormed the barriers of the hangar area. After some heated discussions, it was decided that the ticket holders would get their money back and some kind of peace was restored.

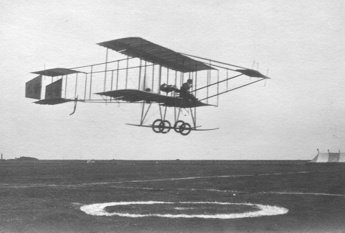

Grahame-White had arrived around noon from Torbay, where he had made exhibition flights. The Farman biplane that he had used there arrived at the airfield around six o'clock and his crew of eight people immediately started assembling it. Grace's machine was complete, but the engine didn't run well. All cylinders were still not firing after some ten minutes of running, so it was rolled back into the hangar. Grahame-White's crew incredibly managed to get his Farman ready for flight in only one hour and three quarters. He took off at 19:39, with only 21 minutes left of the day's official flying time. He flew a couple of laps of the airfield and then steered out over the countryside over nearby St. Anne's. Being the only one to fly, he of course won the day's endurance and general merit prizes.

Friday 29 July

It was typical seaside weather, sunny and bright, but very windy, so it was impossible to fly. The Farman of Robert Loraine and the Blériots of Armstrong Drexel and William McArdle arrived during the day. Loraine hoped to be able to make a flight around six o'clock, but the wind increased again, so it was a completely wasted day.

Saturday 30 July

It was still very windy during the morning, and even though the wind dropped somewhat during the early afternoon nobody made any flights until 15:45, when Loraine took off. He completed the first half of a lap, but when reaching the western end of the course he thought it would be too dangerous to make the tight turn inside the airfield. He left the airfield and made a wide turn over the golf course south of the airfield and returned on the eastern side. He then tried to repeat the performance on the next lap, but a gust of wind forced him down on the golf course, just behind a bunker. His explanation was that he had carried to much weight, because his big tank was full of fuel. His crew brought a smaller tank to the golf course and with the plane lightened he managed to fly back to the airfield.

Soon afterwards Grahame-White made an effort for the altitude prize. He left the airfield in his Farman, flying southwards to St. Anne's, and stayed in the air for 15 minutes. His altitude was at first given as 399 metres, but when the barograph was checked the official figure was reduced to the 251 metres that he had reached while inside the airfield. It was still a good performance in the difficult conditions. The wind speeds varied between 7 and 10 m/s and it was very gusty. Afterwards he took his trainee Clement Greswell as passenger and made a twenty-minute flight further south over Lytham Pier.

Around six o'clock McArdle borrowed one of Grahame-White's Blériots to make a test flight. After climbing to 20 or 35 metres he found that the machine didn't have enough power to make way against the wind, so his circles drifted him further and further to the east. He finally found a suitable field, more than three kilometres from the airfield, and managed to land safely. Grahame-White took off to search for him and landed in the same field. Grahame-White flew back, but the Blériot had to be towed back to the airfield during the evening.

While Grahame-White was away, Drexel made a flight in Grace's Blériot and reached an official altitude of 195 metres. His flying was erratic, and it was obvious that something was wrong with the plane. His landing was dramatic. He first tried to glide in against the wind, which resulted in a perfectly vertical descent. When approaching the ground, he realized that the machine would travel backwards after touching down and decided to go around. After a few "frightful lurches" he got the engine going and after some sharp turns to avoid the buildings inside the airfield he managed to land without breaking anything. When the machine was inspected after the flight it was found that the rigging wires in the fuselage were slack, which allowed the tail to twist in relation to the wings. For the skill and daring displayed during that flight Drexel was awarded the daily merit prize.

Sunday 31 July

No events were scheduled for the Sunday, but the hangars were open for the public. At five o'clock Grahame-White took off and flew northwards. He followed the promenade past the Blackpool Tower to the North Pier, where he turned back and passed the Victoria Pier (now known as the South Pier) and he landed on the beach in front of the club house of the Lancashire Aero Club, where he had some refreshments. A huge crowd had gathered at the machine when he came back to the beach in order to fly back to the airfield. Policemen and club members managed to clear a space in front of the machine, only some twenty metres wide and sixty metres long, but enough to make a reasonably safe take-off. Later in the afternoon Grahame-White invited Mr Talbot Clifton, the owner of the land surrounding the airfield, to a trip around the field.

Monday 1 August

This was a bank holiday and fortunately the weather was finally perfect. The first man to fly was Grahame-White, who took off at eleven o'clock and flew across the Ribble estuary to Southport, some 15 kilometres south of the airfield. He landed on the beach and was once again surrounded by a crowd of curious holiday visitors. It was only with great difficulty that mounted policemen could clear enough space for him to take off again, and he didn't return to the airfield until after one o'clock.

Before the official flights started Howard Harding took out his JAP for some tests. He had made the qualification flights required for a French licence at Amberieu, but there were some problems with the French Aéro-Club's paperwork, so his licence had not been granted and he was therefore not allowed to make official flights during the meeting. His license wouldn't be officially approved until August 29th.

Greswell made some ground rolls and short jumps on the "Bluebird", a blue-painted Anzani-engined Blériot owned by Grahame-White. When he tried to make a proper take-off he lost control and a wheel buckled. The machine crashed on its side, but without injury to the pilot. McArdle was next, again borrowing one of Grahame-White's Blériots. He amused the crowd with some roller-coaster flying during a ten-minute flight, but when he touched down after a long glide he mixed up his controls and landed heavily on one wheel. The wheel buckled and the resulting crash damaged the landing gear, the propeller, the engine bearers and a wing, but again the pilot walked away unharmed. Drexel rolled out his new two-seat Blériot, which he had bought from Léon Morane after the Bournemouth meeting. He planned to take Grace as passenger on a flight around the Tower, but a tyre blew already in the hangar area.

At half past two Jorge Chávez took out his new Blériot for the first time and immediately left the airfield and flew north towards Blackpool. He climbed very high, his barograph showing 1,128 metres, but since the highest part of the flight was outside the airfield he was officially credited with only 777 metres. It was still enough to win him the day's altitude prize. Grace took off in his new Blériot and made a flight of eight and a half minutes. He started a second flight, but during the take-off run the ignition control didn't work when he tried to shut down the engine. He found himself a passenger in a runaway plane, and although he shut off the fuel supply the engine didn't stop until he had ground-looped, breaking the landing gear and the propeller. Drexel took off again after replacing the blown tyre. The engine lost power after a while and he landed in a field outside, after narrowly clearing the airfield fence. Chávez made a second flight, this time for 27 minutes, and finished it with a beautiful glide from a height of 600 metres.

Loraine was next to try, but he had trouble with a seized wheel bearing. He took off at 15:15, when the wheel had been replaced. He circled the airfield once, and the left towards the south. Messages reported that he had flown over the north part of Liverpool, across the Mersey, round New Brighton Tower in Wallasey, almost 40 kilometres south of the airfield, and back via Southport. He landed on the beach at Fairhaven, some ten kilometres from the airfield, after a flight of one hour and fifty minutes. The reason for landing was that oil from the engine had saturated the fabric of the horizontal tail, which then started to come off the ribs. This reduced the lift of the tail and made the plane fly with the tail dangerously low. The plane was threatened by the tide, which was quickly rising, but it was saved by the large crowd of curious people who came wading over the flooded beach. His crew drove out from the airfield and repaired the tail, so that he could make the ten-minute flight back to the airfield, where he arrived shortly before seven o'clock.

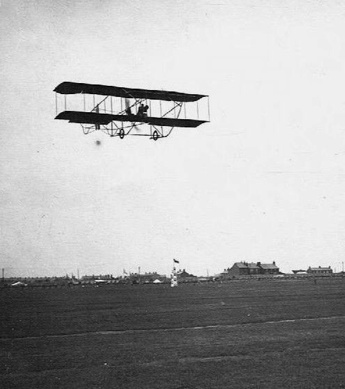

Loraine's flight didn't count for the daily endurance prize, since he had landed outside the airfield. The prize was taken by Maurice Tétard, whose Sommer machine had finally been delivered after some transport delays and had been readied during the morning. He flew for almost two hours, including a circle around the Blackpool Tower, and impressed the spectators with his solid, steady flying. The disappointed Loraine made a 43-minute flight after returning to the airfield, which earned him the second prize.

Roe had worked hard for four days putting together a new triplane from spares, in order to replace the two that had burned on the train to Blackpool. It was now ready for a test flight, even though he didn't have enough tyres and three of the four wheels only ran on the rims. He impressed with the machine's ability to make tight turns.

Grahame-White made several passenger flights during the afternoon, most of them with ladies, one of them being Mrs Huntley Walker, the wife of the chairman of the Lancashire Aero Club. He also took up 16-year old Avice Rivett, who was claimed to be the youngest woman to ever had flown. During the last of the flights he had engine troubles and landed on the North Shore golf course, seven kilometres from the airfield, where he dropped the passenger. After fixing the problems, he flew back to the airfield and landed at 20:20. Grahame-White was given the day's merit prize for his impressive displays of flying skill, for example easily flying figure eights. Roe was awarded a special merit prize of £ 50, given by Sir Peter Walker, for his efforts. The 24,000 spectators had certainly got their money's worth during a day that, according to "Flight", had not been equalled in the history of Great Britain.

Tuesday 2 August

Those who had hoped for another day with good weather were disappointed. It was rainy and windy, with wind speeds reaching 13.5 m/s. The airfield was deserted and the only ones who had any reason to be pleased were those with machines that needed repairs. At half past seven Roe brought out his triplane and made a couple of long hops, with a bent wheel axle as the only result. A few minutes later Grahame-White took off and flew two laps of the course, the machine rocking and pitching in the violent gusts, which by now reached 15 m/s. Against the wind the machine hardly moved forward, but with the wind from behind it travelled at more than 110 km/h over the ground. After landing, he took off again and flew two more laps. It was a great display of airmanship, but after his landing everybody was relieved that there had been no accident.

Wednesday 3 August

The weather changed completely again before the last day of the first week, and conditions were perfect in the morning. Grace and Roe had repaired their machines and were ready to fly again. Roe was first to try, at around three o'clock. He flew two low laps and then landed heavily, breaking two wheels.

During the afternoon Grahame-White, who was an active supporter of military aviation, participated in some war games that were intended to prove the usefulness of airplanes for the armed forces. It was pretended that England had been invaded by an enemy and an infantry brigade had been cut off and surrounded by the enemy at the Club House in the middle of the airfield and needed to send messages to the headquarters at Lytham Hall, six kilometres away. Harry Harper of the "Daily Mail" acted as the general commanding at Lytham, and Harry Delacombe of the "Morning Post" as the officer in command at the airfield. Grahame-White rolled across the ground from the hangars to the Club House, received the messages and then took off for Lytham Hall. He soon returned and set off again with other despatches, taking with him a photographer for taking photos of "the enemy's troops".

While Grahame-White was away, Tétard came out on his Sommer biplane and began circling the field at low altitude. Chávez rolled out his Blériot, intending to go for the altitude prize. Carrying a barograph suspended from his neck, he quickly climbed very high in wide circles, and it was speculated that he could perhaps even beat the world altitude record. This stood at 1,902 metres, reached on July 10th by Walter Brookins on a Wright at Atlantic City, but not officially verified by the US Aero Club until August 2nd. After a quarter of an hour he gave up and started to descend in steep glides. He touched down after a flight of 24 minutes, complaining of the cold at the high altitudes and remarking how difficult it was to locate the airfield from above. The officials immediately got to work checking the barograph. They declared that the altitude reached had been 1,794.5 metres, which beat Jan Olieslagers' and Jules Tyck's results from the Stockel meeting in Belgium two days before, but not the world record.

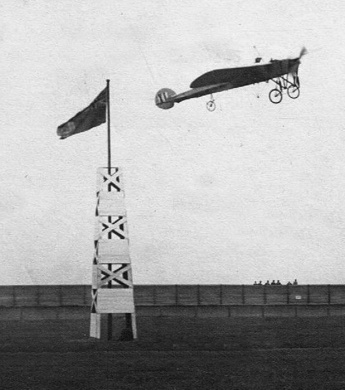

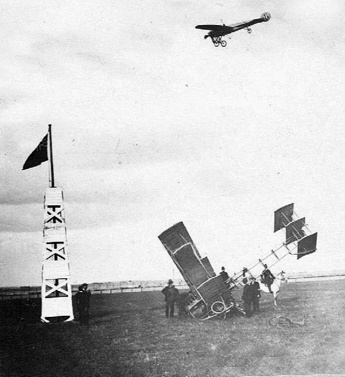

Chávez was followed by Drexel. He had also intended to go for the altitude prize, but evidently changed his mind when he heard of Chávez's result and instead amused the crowd by manoeuvring above the field. While he was flying, Loraine rolled out his machine, but the tail problems from two days before were obviously not completely solved, and he landed almost immediately. His war games finished, Grahame-White turned to the endurance prize and started circling the filed. He was followed by Drexel, who was going for both the endurance and altitude prizes. Roe had repaired his wheels and took off at five o'clock. He made a very quick take-off, but when making a turn he was caught by a gust and headed straight towards the pylon. In order to avoid it he went for the ground and landed heavily, damaging a wing section and breaking the propeller and some struts.

At six o'clock, after Grahame-White and Drexel had taken off again in their battle for the endurance prize, Grace brought out his machine. He made a good take-off, but it was obvious that the machine was not in trim. The machine leaned to one side and it seemed that the problems got worse and worse. He switched off the engine to land, but had to restart it in order to regain control. He bounced heavily on the right wheel, which buckled, and when he again came down on the wheel the landing gear broke, and the propeller and one of the wings were damaged in the resulting crash. Afterwards, Grace explained that the wings had been asymmetrically rigged by mistake.

At seven o'clock it started raining and the wind got stronger, so the crowds started leaving. At that time Grahame-White led the battle for the endurance prize by only thirteen minutes, so Drexel came out again at 19:39, trying to beat him. Grahame-White didn't want to be beaten, so he took off four minutes later, followed by Tétard, who had been troubled all day by fuel feeding problems. When the official timing stopped at eight o'clock Grahame-White had covered 2 h 03:24, defending his lead over Drexel's 1 h 54:26. The day's merit prize went to Chávez, for his British record altitude flight. Grahame-White won the Daily Telegraph's cup and £ 200 for the weeks most meritorious performance, bringing his total earnings over the week to £ 650.

Conclusion of the first week

With only two good flying days, and with the delayed hangars and late arrivals of several flyers, the first week was a bit of a disappointment. The organizers calculated the loss to around £ 10,000 and hoped that the following weeks would compensate. The hospitality and the arrangements were praised by press and visitors, who compared the meeting favourable with the previous British ones. Now there would be eleven days of displays and exhibition flights before the second half of the competitive flights.

Exhibition flights

Grahame-White and Tétard had been contracted for flights, the former for a fee of £ 2,000. It was expected that Roe, Harding and Loraine would also make flights, while some of the other pilots travelled to Lanark to participate in the meeting there. Here are some brief highlights:Thursday 4 August: A windy day. Grahame-White and Tétard made several flights. Harding failed his first attempt for a British licence qualification flight.

Friday 5 August and Saturday 6 August: No flying. The Blackburn monoplane had arrived, but would not make any flights during the meeting.

Sunday 7 August: Tétard made several flights, some with passengers. He twice flew over the town and rounded the Tower. Roe and Harding made short flights.

Monday 8 August: A fine day, with 10,000 spectators and several flights of Tétard, Roe and Grahame-White. The latter suffered a broken propeller from a stone that was kicked up by a wheel. Harding flew two laps. The committee had arranged that one out of every 500 tickets would win a passenger flight with either Grahame-White or Tétard. The numbers were drawn at half past four and written on a blackboard that was carried round the ground. Those holding a ticket with a winning number were invited to claim the flight. Only about half a dozen of the winners did, and one or two sold their tickets to more daring people.

Tuesday 9 August: A bright but windy day with 5,000 spectators. Flying didn't start until four o'clock. Grahame-White, Tétard and Roe made several passenger flights. During a solo flight, Roe landed downwind and lost control during a turn, putting the machine on its back. He injured an ankle and had to use crutches for four days.

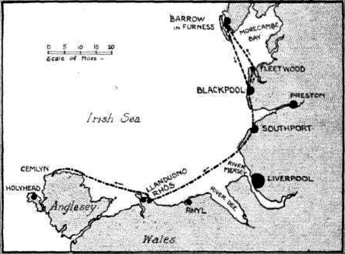

Wednesday 10 August: Loraine took off at half past six in the morning, planning to fly to Ireland. He landed on a golf course at Rhos, near Llandudno in Wales, after a flight of almost 100 km, much of it over water. He then got lost on his way trying to reach Holyhead. Low on fuel after two hours, he landed at a farm near Cemlyn on Anglesey, where the biplane was stored for the night.

Grahame-White took off at 10:50 and landed at Fleetwood Barracks. He then flew past Morecambe, but since it was misty there he continued across the bay to Barrow-in-Furness. After a short rest he flew back to the airfield and landed at 12:50. During the late afternoon Tétard, Grahame-White and Harding made several flights.

Thursday 11 August: Grahame-White took off at 6:45 in the morning towards New Brighton, but had to land already at St. Anne's with valve problems. His crew drove out from the airfield and fixed the problems, enabling him to take off at 09:45 and land at the New Brighton Tower shortly before eleven o'clock. The almost 40-kilometre flight back to the airfield only took 27 minutes, with the help of a good tailwind. In the afternoon there were "the usual exhibition flights". Loraine had to stay at the farm in Cemlyn because of strong winds.

Friday 12 August: It was rainy in the morning and winds were strong all day, so there was no flying. Loraine tried to continue his flight to Ireland, but his engine didn't run well and he couldn't climb high enough to clear some uneven ground. The landing gear collapsed and the machine was severely damaged, but Loraine escaped unhurt.

Saturday 13 August: Grahame-White had set himself the target of flying at least 100 miles on each of the last two days in order to win the £ 1,000 Daily Mail prize for the greatest aggregate distance flown across country, which closed on August 14th. He flew first to New Brighton and then to Morecambe, adding 110 miles to his total. Conditions were very favourable during the afternoon and all flyers made flights, Roe needing a bicycle to get around the hangars because of his injured ankle. Grahame-White practised bomb-throwing, dropping flour bags against a target in the form of a battleship. Late in the afternoon Grahame-White made another flight to New Brighton.

Sunday 14 August: Grahame-White flew back and forth three times to New Brighton, while Tétard, Roe and Harding made regular flights around the airfield.

The second week

It had been hoped that several of the competitors from the Lanark meeting would come to Blackpool for the second week, but the only additional pilots that were ready from the beginning were Bartolomeo Cattaneo and James Radley, and the latter in the end never made any flights. Chávez didn't come back, since his machine had burned on the train near Lancaster on the way to Lanark. Champel had damaged his machine in Lanark, as had Dutch Antoinette pilot Gijs Küller, who had also announced his intention to participate.The prize structure was different during the second week. The daily prizes were smaller and prizes for the best performances over the entire week were introduced. Prizes for speed, quickest take-off and bomb-dropping were added.

Monday 15 August

The sun shone brightly, but a strong breeze blew all day. During the afternoon the wind decreased somewhat, but the anemometer still registered 13 m/s, with gusts up to 16 m/s, when Grahame-White bought out his Farman at five o'clock. He flew a lap and a half, the machine "rocking and swaying like a piece of paper" in the wind. He then announced that he would try for the take-off prize, but his efforts were delayed until 17:40, when the necessary measuring tapes had been found. The best of his two official efforts was 7.49 metres. He made a third try afterwards and managed to get off in 6.32 metres, which was claimed to be a world record. Somebody observed that with a strong enough headwind it would be possible to lift off vertically, but it was still a display of skill and courage, not least of his ground crew, who had to hold the plane down before the take-off. At seven o'clock Roe tried for the take-off prize, but failed both times. Half an hour later Grahame-White tried again to improve his previous results, without success. Nobody else flew during the day.

Tuesday 16 August

Although it was still windy the weather had improved considerably, and a large crowd had travelled out to the airfield. Flying started at a quarter past three, when Roe made a short flight along the airfield and back. He was followed by Drexel, who flew ten laps in 19 minutes, still troubled by the wind and flying crabwise along one of the straights. Grahame-White was next, making a flight of some 23 minutes, also troubled by the turbulence. Cattaneo took off at around half past four, climbing quickly to some 60 metres and glided back to land after ten minutes. Roe made a second short flight, this time with a passenger. At five o'clock Tétard took off to go for the duration prize and stayed in the air for 37 minutes, which would prove to be the day's longest flight. Grace took off some minutes after Tétard and obviously wanted to be careful after his two previous accidents. He climbed to a safe altitude of 200 metres and tried the machine out by making glides and different manoeuvres. Roe took off for a two-lap flight, making it three planes in the air - a monoplane, a biplane, and a triplane! When Roe had landed, McArdle took off and started circling the field at high speed. Grace landed at 17:41 after a flight of 34 minutes. Three minutes later Mc Ardle landed, and Cattaneo took off again and quickly climbed to 300 metres, before making another beautifully judged landing glide. At six o'clock Grahame-White and Drexel took off simultaneously, the former with a passenger on board. Neither stayed in the air for more than a few minutes. At 18:06 Grace took off to go for the altitude prize, followed by another passenger flight by Grahame-White. Grace gave up his effort because of the variable winds, but the 387 metres that he reached would prove enough to win the day's altitude prize.

The speed contest started half past six, but the wind had increased, so nobody expected exceptional speeds. There were only two entrants, McArdle and Cattaneo, and according to the rules they would each be alone on the course. McArdle took off first and was beaten by the narrow margin of 0.6 seconds, Cattaneo scoring 3:36.0 over the three laps.

At seven o'clock the bomb-throwing contest started, with Roe, Grahame-White and Tétard entering. Roe made the first effort, but got too low and touched the ground with a wing tip and crashed. Grahame-White, who had practised on the battleship target the week before, won the contest with ease.

Grahame-White had won the day's total time prize with a sum of 51:18.8, with Grace second. Tétard's 17 laps won him the total distance prize. After the end of official flights, the repaired "Bluebird" Blériot was rolled out for a test, but it didn't work very well. Radley failed to get it off the ground and then Grahame-White tried, but never got more than five feet off the ground during a hop of a few hundred metres.

Wednesday 17 August

Wind speeds were again up to 13-14 m/s, so there were no flights. There were quite a number of spectators at the airfield, but they had to contend themselves with watching work in the hangars. The main attractions were the repairs of Roe's triplane and the assembly of Launcelot Gibbs' Farman, which had arrived from Lanark. Towards the end of the afternoon it started raining and many people left the airfield.

Thursday 18 August

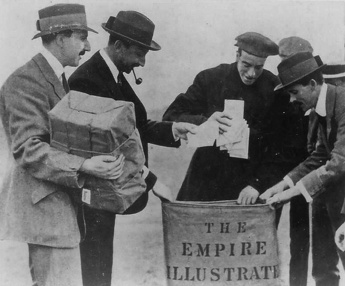

The weather was reasonable in the morning, but still rather windy. Grahame-White, who never wasted a chance to promote aviation, had planned an air mail experiment. A bag, labelled "Aeroplane Mail" and containing several thousand postcards, was strapped to the machine behind the seat, with the intention to fly them to Southport. The machine he intended to use, an English-built Farman, had been modified by shortening the rear fuselage by one fuselage frame, a modification that had been made to some French Farmans. It was soon obvious that machine was not in trim and after a "short and exciting" flight it was returned to the hangars. Just before noon Roe's trainee Howard Pixton brought out the triplane and made several long hops, but the wind discouraged him from further attempts. At two o'clock the weather turned worse. It started to rain heavily, and it continued the rest of the day.

Friday 19 August

The rain was followed by a severe gale, which tore the roof off several hangars. Fortunately no planes were damaged, and they were quickly moved to the hangars that still had a roof. The more solidly built permanent hangar of Blackpool aviator Mr. Lumb housed four airplanes. A captive balloon, which had been briefly flown the day before, had its envelope split open, and a large refreshment tent collapsed. In the afternoon the wind speeds ranged between 15 and 25 m/s and all flyers except Grahame-White and Tétard started dismantling their planes.

Saturday 20 August

It was grey and gusty in the morning, but the sun broke out after two o'clock and quite a number of optimists ventured to the airfield. At half past three, Grahame-White tested his machine before continuing his mail flying experiments. He flew two unsteady laps in the difficult wind and returned to the hangar for more adjustments. He was out again at five o'clock, but by then the wind was too strong. Drexel and McArdle had started to reassemble their machines whrn the weather looked like it would improve, but they soon gave up. At a quarter to six Grahame-White brought out the machine, announcing that he would try for the endurance prize. It was now very windy, and everybody at the airfield followed his flight. The unfamiliar modified machine was tossed around violently by the gusts and was several times saved from disaster at the last moment. Grahame-White landed after 17 minutes and the committee decided to award him the day's endurance prize, even though he hadn't reached the required 20 minutes. He had cramp in his left arm after fighting the machine for so long, and it took several minutes for him to recover.

Grahame-White's flight secured his win in the weekly total time and distance contests, and his performance during the meeting confirmed his status as one of the most accomplished pilots of the world. All the other results stood unchanged after the Tuesday.

Conclusion

During the few good flying days, only three days during the two weeks of contests, the meeting certainly lived up to expectations, but from a financial point of view the meeting was a disaster. It was calculated that the total loss would reach £ 20,000. The loss could of course to a large extent be blamed on the weather, but the lack of support from the municipality was also mentioned as a contributing factor. The high number of non-paying spectators was also a disappointment. The Lancashire Aero Club would not arrange another aviation meeting.