Blackpool, UK, October 18th - 24th 1909

Almost the first air race meeting in the UK...

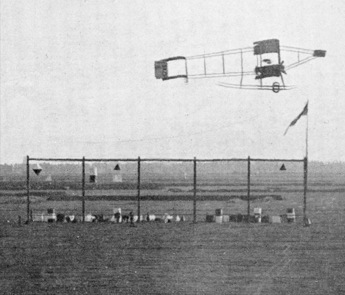

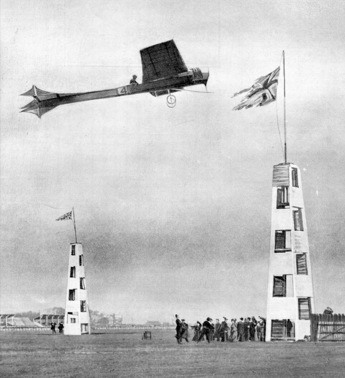

White/black double cone: the Daily Sketch prize for speed White/black cylinder: GP of Blackpool for long distance

Black cone, white cylinder: Rougier

Black cone: (incomplete) wind speed indication (2)

Blackpool, "Mecca of the Lancashire holiday makers"

according to "Flight" magazine, was the biggest resort in

north-western England. Among the attractions were eleven kilometres of

sandy beaches, the promenade with its piers and amusements, three

theatres, an aquarium, the Winter Garden entertainment complex and the

158 metre Blackpool Tower, modelled on the Eiffel Tower. In 1909 the

town's population was around 50,000, but the number of visitors was

estimated at three millions per year.

It was natural for the leading people of such an enterprising town to

look for new attractions, and what could be more natural than an

aviation meeting. A delegation from the town, including the Mayor,

visited the "Grande Semaine d'Aviation" of Reims in

August 1909 and in the beginning of September it was decided to go

ahead with the planning.

A prize fund of over £6,000 was quickly raised, the main contributors

being the Blackpool Corporation (which ran the trams and other

services), Lord Northcliffe and Sir Thomas Lipton. The owners of the

Blackpool Tower offered a prize of £500 for a flight round the tower,

which was turned down on safety grounds. In order not to frighten

visitors away by overcharging, the Blackpool Corporation agreed with

the hotels and boarding-houses in the town that their charges during

the week should not be more than five per cent higher the usual rates.

The Lancashire Aero Club was formed and arranged the lease of the

airfield, which was situated on a golf course some three kilometres

south of Blackpool, and built a clubhouse, hangars and repair shops.

Their ambition was to "create an English edition of Port

Aviation". The famous French pilots Henry Farman, Louis Paulhan,

Hubert Latham, Henri Rougier and Alfred Leblanc were engaged, no doubt

attracted by the appearance money, which was generous, although not as

high as at the Doncaster meeting. Some less known British flyers were

also entered, as was the France-based Spaniard Antonio Fernandez in a

plane of his own design. Preparations apparently ran smoothly and the

installations were ready for the opening day.

Monday 18 October

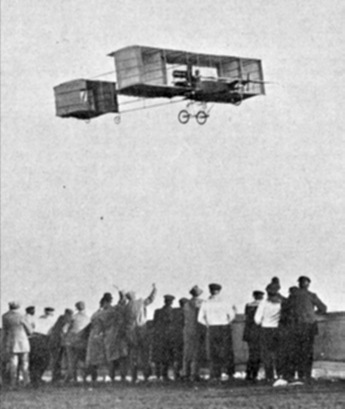

The weather on the opening day was perfect, with sunshine and only a

light breeze greeting the 60,000 spectators. The first pilot to make an

effort, shortly after noon, was A. V. Roe in his triplane. He had lots

of problems getting his JAP V-twin engine started. When it finally ran,

a bracing wire came loose after a long ground run in the underpowered

plane and it had to be hauled back to its hangar for repairs. Soon

afterwards Farman made the first successful flight, completing a test

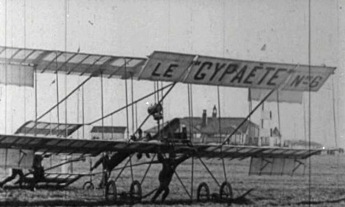

hop and then a lap in Paulhan's new "Gypaète". They

shared Paulhan's plane during the meeting, since Farman's own

was reported to be held up somewhere on the French railways. Then

Paulhan took over the plane and flew another lap. At 15:20 Farman

returned and took to the air in order to go for the "Daily

Sketch" three-lap speed prize. He flew seven laps in just under 23

minutes, the last lap at a speed of 59.98 km/h. His speed over the best

three laps was 58.54 km/h (36.38 mph). While he was flying Rougier made

a test flight. After landing to repair his rudder he then took off for

what turned out to be the day's longest flight. He covered nine

laps in his slower Voisin, totalling 28.8 km in 34 minutes. Towards the

end of his flight Paulhan started for a six-lap flight, but he

couldn't beat Farman's times, his best lap being 54.37 km/h

(33.79 mph). Leblanc flew a single lap in his Blériot, as required by

his contract. This was his only flight during the meeting, and it

didn't count for any of the events, since he didn't pass the

start line correctly. The last flight of the day was made by Farman,

with Paulhan as passenger.

Tuesday 19 October

The day started a little windier than the day before, and the wind from

the sea got stronger and gustier during the day. Farman and Paulhan

were busy fitting a larger fuel tank, so Latham was the first to make a

flight, at around 12:15. He had covered less than half a lap when his

front skid hit a mound. The tail flipped high in the air after the

impact, but Latham managed to hang on to his seat. The rough landing

resulted in a ripped-off skid, a broken wheel and a bent propeller. Roe

made a new effort, with slightly better results, but he only managed

two short jumps. Towards the afternoon Paulhan flew eight laps,

staggering and lurching in the gusts, but due to the stronger wind, by

now some 7 m/s, he could not improve on the times of the day before.

Rougier had also brought out his plane, but decided against flying in

the strong wind. Fernandez also brought his plane out, but didn't

manage to leave the ground.

By four o'clock increasing winds and a heavy rain shower forced the

black flag to be flown, signalling the end of a disappointing day for

the 30,000 spectators. On the Tuesday it was announced that the FAI had

decided that course lengths should be measured from pylon to pylon,

along the inner line of the course. This meant that the distances and

speeds, which had previously been based on the distance along the

middle of the course, had to be recalculated. The new course length was

given as 3.197 km (3496 yards).

Wednesday 20 October

After a very rainy night the morning broke fine and the wind was not

too bad. Singer brought out his new Voisin, but the tail was rigged

with too much incidence and repeatedly made the nose hit the ground. A

Blériot recently bought by the Blackpool Councillor Mr A. Parkinson was

also briefly tested on the ground. Fernandez brought out his plane at

around 10, but only made an unsuccessful attempt, after noon. Farman

brought the "Gypaète" out at around one o'clock and

immediately started to fly like clockwork, with almost identical lap

times and at constant minimum altitude. While he was flying Paulhan

marked the length of the flight by laying a white handkerchief on the

ground for each fifteen minutes flown. After 1 h 32:16.8 and 24 laps,

and presumably six handkerchiefs, he landed, complaining of cramp and

hunger, having set a new British endurance record. The wind increased

again, forcing Rougier to abandon a flight after only 12 minutes. Then

Paulhan took off, but landed after only one lap to replace an aileron

which had been broken when the plane was caught by gust during the

take-off. After the repairs the wind was again reaching 11-12 m/s in

the gusts and he withdrew to the hangar after half a lap. Latham

brought his repaired Antoinette out, but landed before the first turn.

Roe also made an unsuccessful start in his underpowered triplane and

Fournier's Voisin was seen outside his hangar for the first time.

Soon after four o'clock the black flag was flown again.

Thursday 21 October

In the morning the wind registered 13 m/s, and during the day it

increased to more than 20 m/s in the gusts. Flying was of course

impossible, but the organisers put up fences in front of the hangars

and charged one shilling for access, so the spectators were at least

able to see the machines being worked on at close distance. The

Antoinette crew made a dynamometer test, anchoring the machine to a

post and measuring the thrust, which was found out to be around 1200 N

(265 lbs). During the afternoon L. Lumb from Blackpool and Jack

Humphreys from Wivenhoe brought their respective machines in to be

displayed, but they would take no part in the meeting.

Friday 22 October

The wind had decreased slightly, but it rained and was very humid. The

local shoe shops made good business in selling rubber boots, which were

needed in order to navigate the sodden grounds. Nobody expect any

flying, but those who braved the weather got to see a flight that was

for a long time regarded as one of the most daring of all time. Around

one o'clock, with the wind speed reaching 13 m/s (30 mph) in the

gusts, the red flag was suddenly hoisted and a horse pulled

Latham's Antoinette out on the starting ground. His first effort

failed when the wind caught one of the wings and made the opposite wing

tip touch the ground. The tail flipped high in the air before falling

back again. Undeterred, Latham made a new try, this time with mechanics

holding the plane down until he had it under control. The plane

immediately rose to around 20 meters and after narrowly avoiding a

collision with the first pylon and crossing the wind at the second

pylon he was driven with the wind from behind at a speed which was

speculated to reach at least 100 km/h. After an agonizingly slow flight

against the wind he again had the wind from his side on the front

straight, and spectators and officials screamed to him to come down. He

didn't, but continued and completed on more lap, working the two

control wheels frantically as the plane was thrown this way and that by

the gusts, "tossed around like a cork in a cataract", before

landing safely after a flight of eleven minutes. The other flyers

carried him off to a lunch where Fournier proposed a toast to

Latham's health. He said that Latham's flight was "the

most wonderful ever attempted" and that he was "clearly the

first man in aviation". Latham's first lap of 40.4 km/h won

him the slow flight price. The second lap was even slower, but he was

blown too far off the course, so the time was disallowed. It has been

stated that he made the flight in order to honour a promise made to the

Countess of Torby, wife of Grand Duke Michael of Russia, during a

dinner the night before.

During the afternoon it was announced that the meeting would be

continued on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday for the benefit of British

competitors.

Saturday 23 October

The rain continued to fall during Friday night and Saturday morning,

turning the hangar area into a lake. Some hangars could only be reached

by planks. Under those circumstances nobody took the risk of any

flights. During the afternoon the wind increased again. The

international part of the meeting was concluded by a dinner at the

Metropole Hotel, offered by the mayor of Blackpool, where the prize

cheques were handed to the winners. The passenger prize and the

altitude prize were not awarded, and the competitions for British

pilots all fell through since they were intended to start on the

Wednesday and coincided with the arrival of the bad weather. No flying

was planned for the Sunday.

Monday 24 October

The weather didn't improve, so at ten o'clock the committee

decided to call off the rest of the meeting. Soon afterwards the wind

decreased slightly, but the field was still very wet. During the

afternoon some of the British aviators tested their planes. Roe had by

now fitted a 24 horsepower engine to his triplane and was the only one

to leave the ground, but only for 40-50 meters. Creese's plane had

apparently been damaged by water in his hangar and his plane

wouldn't leave the ground. Saunderson and Neale did not manage to

make any flights.

Conclusion

The 1909 Blackpool meeting can hardly be called a success, even though

Farman's and particularly Latham's flights went into the

history books. All in all, only four pilots managed to fly a complete

lap during the meeting, and this includes Leblanc's single flight.

The total distance flown during the meeting was around 186 kilometres.

It was natural to compare the Doncaster and Blackpool meetings. It

appears naïve to organise anything that requires good weather in

England in the end of October, and attendance at both meetings was

badly hit by the rain and wind. The controversy and competition between

the meetings certainly harmed both. Painful as it must have been for

the Royal Aero Club, it appears that the Doncaster meeting was more

popular with the spectators. It was held at a pre-existing horse race

course where infrastructure such as restaurants was already at hand.

The Blackpool airfield with its temporary installations was in an

exposed position, only a couple of hundred meters from the windy Irish

sea, and the proximity of the holiday centre of Blackpool with its

hotels, restaurants and nightlife, and trams running to the airfield

gates, could not compensate for this disadvantage. Blackpool was also

criticised for the high number of policemen and for the attitude of the

officials. The British aviator John Neale wrote a very critical letter

to the "Daily Mail" about the leaky hangars and the way the

British flyers were treated by the organisers.

The Blackpool meeting also lost money, but not as much as the Doncaster

meeting. The appearance money paid to the pilots was considerably

lower, £ 4,200 compared to £ 11,600, which certainly helped.